A Review of Collin Hansen’s Timothy Keller: His Spiritual and Intellectual Formation (Zondervan, 2023)

In a world of political and cultural polarization, Tim Keller is an enigma who defies easy categorization.

He is a northerner raised in mainline Protestantism, yet as a young adult he joined a southern conservative denomination and became its most famous pastor.

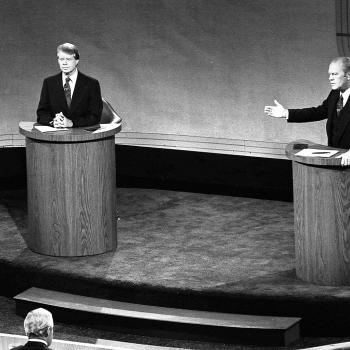

He is a white evangelical and registered Democrat who has criticized the Christian Right and Christian nationalism in the pages of the New York Times, yet he opposes abortion and sex outside of heterosexual marriage, and he refuses to endorse the principles of the Democratic Party or become involved in politics in any way.

He has spent decades advocating for racial justice and concern for the poor, yet he considers Jonathan Edwards, an enslaver, one of his greatest American theological influences.

His wife Kathy – with whom he has cowritten books – was once a candidate for ordination as a pastor in the United Presbyterian Church, but both he and Kathy have embraced gender complementarianism for decades.

His New York City church, he has long insisted, is neither fundamentalist nor mainline.

So, how should we understand Keller? What enabled a small-town pastor of a backwater church in rural western Virginia and who was a mediocre seminary student (he earned a C in his preaching class at Gordon-Conwell) to plant a church in New York City that became a congregation of thousands and to become a nationally known author with a book on apologetics that reached number seven on the New York Times bestseller list? What enabled Keller to remake his own denomination and arguably even evangelicalism itself – or at least the Reformed wing of it – while remaining sharply critical of contemporary evangelical political trends?

Collin Hansen’s new biography of Tim Keller suggests that the answer is Keller’s conversion experience and understanding of the gospel.

That’s not an answer that many historians would like. It seems to remove Keller’s experience from the realm of all of the historical forces that we like to study – forces such as culture, economics, demographics, gender, race, class, and power dynamics – and treats Keller as an ahistorical candidate for hagiography.

But that doesn’t need to be the case. Keller’s conversion experience may in some ways be historically transcendent, but it is also very much rooted in a particular time and place – and that time and place begins with northern evangelical circles in the early-to-mid 1970s.

Born in Pennsylvania in 1950, Keller has lived most of his life north of the Mason-Dixon line, and he was shaped by many of the influences that shaped Baby Boomers in the Northeast.

Like many people raised in the 1950s, Keller grew up going to church – mostly in a mainline Lutheran denomination, but with occasional Catholic and Wesleyan influences as well.

By his own account, his knowledge of the “gospel,” as he later came to understand the term, was nearly nonexistent. If he had been asked at the time what it meant to be a Christian, he might have said “be a good person.”

When he was in middle school, one evangelically minded Lutheran minister introduced him to the Lutheran distinction between law and grace, a revelation that Keller found eye-opening and that he thinks could have led him to a saving knowledge of Jesus.

But the next year, a liberal Lutheran pastor presented a completely different form of Christianity – one that had almost nothing to do with individual salvation and everything to do with social justice. Following Jesus, he said, meant enlisting in the civil rights movement – and nothing to do with trusting in an atoning sacrifice to appease a wrathful God.

“It was almost like being instructed in two different religions,” Keller later recalled. “In the first year, we stood before a holy, just God whose wrath could only be turned aside at great effort and cost. In the second year, we heard of a spirit of love in the universe, who mainly required that we work for human rights and the liberation of the oppressed. The main question I wanted to ask our instructors was, ‘Which one of you is lying?’”

By college, Keller had decided that perhaps neither minister had the truth. While majoring in religion at Bucknell, surrounded by professors who gave him numerous arguments for not trusting the historicity of the Bible, he (like many other mainline Protestant Baby Boomers in the late 1960s) lost much of whatever Christian faith he had, but began exploring the possibility of finding spiritual meaning in other religions. He was somewhat attracted to Buddhism, yet felt that the lack of a personal God in Buddhism was a loss he didn’t think he could live with.

Then he discovered an Intervarsity Christian fellowship that led him to the writings of C.S. Lewis and a better understanding of the gospel than he had ever received. For a few months, he wrestled with the ideas that he was learning, but then surrendered his life to the Lord.

His friends noticed an immediate change. “He was a heck of a lot kinder, and you could reach him emotionally,” one of his friends later recalled. “All of a sudden he was present. He was there.”

His friends also noticed that he no longer seemed to care much about his grades. Evangelism and Bible study became much more important to him than writing college papers. After college, he entered Gordon-Conwell with the intention of seeking a pastoral career.

Northern evangelicalism of the early-to-mid 1970s was politically diverse, but focused heavily on individual conversion and evangelicalism. The defining experience for most evangelicals was the moment of being “born again”; it determined whether one was a genuine Christian or not. This was true for Keller as well. Though he wondered at the time why so many evangelicals he met seemed to care so little about the civil rights movement or racial justice, he mostly kept quiet about the social justice causes that were important to many people of his generation, and instead threw himself into efforts to pursue individual sanctification for himself and the conversion of others through personal evangelism. Like many conservative evangelicals of the 1970s, he soon became convinced that the Bible was the inerrant word of God.

At the time, he was a Wesleyan Arminian, though the distinction between Arminians and Reformed Christians mattered less to many evangelicals in the 1970s than it would a generation or two later. When Keller entered seminary, he planned to become ordained in the small Wesleyan denomination he was a member of at the time. Yet the best preaching he ever heard came from Reformed evangelicals – theologically conservative Presbyterians in particular.

He had Wesleyan professors in seminary as well as Reformed ones, but after hearing both perspectives, he decided that Reformed theology made sense of the Bible in a way that Arminianism did not. The biblical story was not primarily about humans and what they needed to do; it was rather about God and God’s work of redemption in Christ.

Keller was a biblical inerrantist, but not necessarily what one would consider a biblicist or a fundamentalist, because his method of reading the Bible was informed as much by his love for stories as by a literal reading of the text. In college, he developed what would become a lifelong love of the fiction of C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien – a love that was so deep that he read and reread not only the Lord of the Rings series but also all thirteen volumes of Tolkien’s posthumously published works, becoming so familiar with them that years later, when he was being wheeled into the hospital operating room for surgery to remove a cancerous tumor, he buoyed himself not by quoting biblical passages to himself but by reciting quotes from Tolkien’s stories.

In Keller’s understanding of Reformed theology, the Bible itself was one grand story of God’s creation, redemption, and promise of restoration. Every individual story in the Old Testament reflected this larger story by pointing to Christ. The story of Abel’s death at his brother’s hand pointed to Jesus’s death. The story of Jonah being thrown into the sea and swallowed by a whale pointed to a greater atoning sacrifice.

Keller thought that most of these stories had really happened, though he deviated occasionally from the literalism of the most ardent fundamentalists. Genesis 1, he decided, was a poetic account that could be harmonized with evolution and an old earth.

But one principle that could never be sacrificed was the idea of substitutionary atonement, which was the key to understanding God’s grace.

Keller believed that self-salvation is the universal human temptation – the temptation of good churchgoing Protestants like the ones he knew in the mainline churches of his youth, the temptation of fundamentalists who embrace “legalism” in their list of Christian dos and don’ts, and the temptation of liberal social justice advocates who, whether in the name of Christianity or secularism, cast moral judgments on those who don’t support their interpretation of justice. Christianity ends our self-salvation projects by interrupting our lives with grace.

But in order to avoid making this merely “cheap grace,” we need a robust theology of substitutionary atonement – a realization that Jesus paid the infinite price for our sins, and we therefore can make no demands on him or on anyone else. Once we realize that truth, our lives will be transformed by a love that will motivate us to follow Jesus’s commands and pursue sanctification – not to earn our standing before God but to live out our calling as followers of Jesus.

As Keller finished his seminary studies in the mid-1970s, he was excited by Reformed evangelical theology, but he also realized that he did not have a denomination that would hire him. He had entered seminary with the stated intention of seeking ordination in the Wesleyan denomination of which he was a member, but once he embraced Reformed theology, he could no longer sign the denomination’s statement of faith.

His wife (Kathy) had entered seminary intending to seek ordination in the United Presbyterian Church (the mainline Presbyterian denomination that became the PCUSA in 1983), but after taking a class at Gordon-Conwell with the complementarian Elisabeth Elliott, she became convinced that a biblical theology of distinct gender roles rooted in the creation order did not allow for the possibility of women serving in senior pastoral roles, so withdrew her candidacy for ordination and soon after left the UPC entirely.

Casting about for a church tradition to affiliate with, the Kellers chose to go with a small southern Presbyterian denomination that was only two years old and that they knew very little about: the Presbyterian Church in America (PCA). Tim was hired to serve as pastor of a small-town church in Virginia, where only two of the members held a college degree and most of the older members had never attended school beyond the 8th grade.

The move from Boston to semi-rural Virginia was a culture shock for the Kellers, but Tim learned to relate to the people through pastoral counseling. By his own admission, his preaching wasn’t very good when he first arrived, but he learned to make it better by spending time listening to people and then preaching sermons that answered their questions rather than his own. It was a skill that he would retain for the rest of his pastoral career – and that was probably the main reason why his apologetic-oriented preaching in New York resonated with so many people.

But after several years in Virginia and a few in suburban Philadelphia, Keller decided in 1989 to move to New York City to plant a church (Redeemer Presbyterian) that eventually began to attract thousands of people. It was in New York that he became nationally known for preaching a message that combined a theologically conservative Reformed evangelical message of biblical inerrancy, substitutionary atonement, and individual justification with a commitment to social justice (especially in the areas of poverty and race).

In Keller’s view, salvation could never be purely individual – even though he did place a primacy on individual justification, followed by individual sanctification. But in keeping with modern Reformed theology, he also believed that God had a plan to redeem the world and culture, all of which were part of God’s grand story. God cared about the environment and the flourishing of cities – and God especially cared about the poor and about racial reconciliation and racial justice.

Keller decided that both of the Lutheran pastors he had met as a 14-year-old – the one who taught about individual sin and grace and the one who promoted the civil rights movement – were partly right: people needed individual justification, but they also needed to care about racial justice.

Christianity, he believed, offered the only hope for racial justice and social justice in general, because it offered the only promise that the justice people were longing for would in the end be achieved. Secular philosophies offered no such assurance.

“Imagine how ludicrous it would have been,” Keller said, “to sit down with a group of early nineteenth-century slaves and say, ‘There will never be a judgment day in which wrongdoing will be put right. There is no future world and life in which your desires will ever be satisfied. This life is all there is. When you die, you simply cease to exist. Our only real hope for a better world lies in improved social policy. Now, with these things in mind, go out there, keep your head high, and live a life of courage and love. Don’t give in to despair.’”

It is only the gospel that gives people the real power to challenge injustice, he believes, because only the gospel can be both the firm hope of real lasting change and the force that will moderate our own desire to demonize our opponents and exact revenge in the name of securing justice.

“If the gospel changes you, you will never see anybody else, anywhere else, as being the enemy, the real problem with the world,” Keller declared. The gospel makes us “more able to cooperate with people, ultimately more pragmatic and more willing to compromise”; it is only “self-righteousness” that makes us look at others as “the bad guys.”

Keller’s combination of social justice and an irenic spirit with theologically conservative, Reformed evangelicalism has attracted a lot of positive attention, but it has also generated criticism.

From the theological left or center-left, Keller has been criticized for belonging to a denomination that does not ordain women and for teaching that homosexuality is a sin.

From the theological right, he has been criticized for suggesting that it’s okay for Christians to vote Democratic, for not saying enough about abortion, for being soft on homosexuality, and for watering down the gospel with an appeal for social justice. Even his irenic spirit has generated criticism from church conservatives who worry that he’s too willing to compromise with the world.

I believe that some of these friction points occur because Keller is a northerner in a predominantly southern denomination at a time when white evangelicalism as a whole is becoming both more southern and more culturally militant. Keller’s particular style of evangelical theology would have been very much at home in the less politically charged milieu of mid-1970s evangelicalism in the Chicago area and other parts of the North.

And if he hadn’t opted for a southern complementarian denomination – a choice that may have seemed less polarizing in the 1970s than it does today – he probably could have ended up in a northern-based, social justice-oriented denomination such as the Christian Reformed Church or the Evangelical Covenant Church that would never have criticized his attempt to link the gospel with a social justice imperative.

But because Keller is thoroughly and unabashedly evangelical – and an evangelical advocate of biblical inerrancy and gender complementarianism at that – his theological associates include a lot of people on the cultural right, such as Al Mohler, who agree with Keller about justification and the atonement but whose own approach to the culture wars is very different from Keller’s.

Keller’s aversion to the culture wars comes not from a conviction that Christians should stay out of politics (he doesn’t believe that) or that the liberals are correct (he doesn’t believe that either) but from a very strong aversion to legalism. Morality without regeneration leads people further away from God, he believes – which means that the people most drawn to self-righteous stances in the culture wars on both the right and the left might be the people least aware of their own need for grace and the least capable of extending grace to others. In Jesus’s parable of the prodigal son, it’s not the self-righteous older brother who ultimately repents; it’s the prodigal.

Morality and justice are critically important in the Christian life, Keller believes, but only as a response to grace. Without grace, they make terrible idols.

So, during what may be the final months of his life as he battles cancer (or, as he claims, battles his sin, since he has said he’s not worried about his cancer as he prepares to enter eternity), Keller is not preaching about the hot-button topics of the culture wars. Instead, he’s leading devotionals that focus on what he has long made the focus of his preaching: the transforming grace of a Triune God.

It’s not a message that all self-described evangelicals will resonate with. But it may be one of the most authentically evangelical messages that we’ll hear today.