“Where does it say that?” he asked.

I handed him my iPad. We stood on the staircase, me traveling down to my office while he traveled up to his. I casually mentioned how the medieval sermon I was currently reading contradicted the resurrected Christ’s directive to Mary Magdalene in John 20:17: whereas the Latin Vulgate records Christ saying “noli me tangere” (do not touch me), the sermon recorded that Christ, “when he rose from death to life, he appeared to [Mary Magdalene] bodily first of all others and suffered her to touch him and kiss his feet.” My colleague, a Reformation scholar, literally stopped in his tracks. I still remember him staring at the image of the fifteenth-century text made so clear on my 21st century technology.

The sermon author was a late medieval priest named John Mirk. I have written about him several times on this blog, but—for a quick refresher—he was an Augustinian canon from Lilleshall Abbey in fourteenth-century Shropshire. He probably also served as vicar at the parish church of St. Alkmund’s in Shrewsbury, a town about 15 miles aways from Lilleshall Abbey. Around 1380 Mirk penned the sermon collection Festial. It soon became the most popular non-heretical vernacular sermon collection in late medieval England with more than 40 extant manuscript copies and multiple print copies.

Which means that Mirk’s version of Christ’s encounter with Mary Magdalene would have been familiar to medieval people, perhaps even more familiar than the actual scriptural account. This is what Juliette Vuille, in her 2013 article “’Towche me not’: uneasiness in the translation of the noli me tangere episode in the late medieval English period,” argues: that medieval authors did not recognize a Christ who refused to touch Mary Magdalene, so they rejected the Vulgate translation of the verse. As she writes, “such late medieval authors as John Mirk, Nicholas Love, and Margery Kempe reflect a deep uneasiness with the Johannine verse, an anxiety evidenced on the page by mistranslations or contradictions of the noli me tangere episode.” Instead of Christ directing Mary Magdalene “to touch him not”, these medieval authors emphasized the close relationship between Mary and Jesus as well as her great faith which outshone even that of the male apostles.

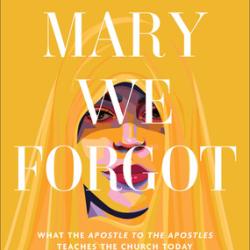

Take John Mirk’s account of Mary Magdalene. He describes her as a repentant sinner who became the most faithful follower of Jesus as well as preacher of the Gospel. As he writes, “But no word spoke she that men might hear, save in her heart she cried out to Christ for mercy, and made a vow to him that she would never trespass no more. Then had Christ compassion on her and cleansed her….and forgave all her guilt of sin.” Just as in the sinner’s prayer, Jesus saved Mary Magdalene from her sins, and her conversion came from a personal encounter with Christ. Her repentance was so sincere that her life was transformed. Mirk notes that when the “disciples fled away from (Jesus) for dread of death, she left him never.” Her faithfulness allowed her to be the first to see the risen Christ–thus making her “the apostle to the apostles”. She became a powerful preacher in France through who “all the land was turned to the Christian faith.” Mirk recorded that her authority was even blessed by the apostle Peter. Indeed, from Mirk’s perspective, Jesus telling Mary not to touch him just did not fit with how he understood the scriptural portrayal of Mary Magdalene. For Mirk, the Vulgate’s wooden translation of John 20:17 was not only an outlier but it was probably incorrect. (FYI some modern translations like the NIV and NRSV seem to agree more with John Mirk, allowing Mary Magdalene to “not hold on to” Christ instead of “do not touch” Christ.)

So why did medieval authors like John Mirk do this? Did they not believe the Bible? Were they just cherry picking the parts they liked? Or did they remember something about Mary Magdalene that we have forgotten?

Let’s return to Juliette Vuille. She begins her fascinating argument by reminding us that Jerome’s translation of the text from Greek to Latin was fraught with difficulties. Almost from the beginning, the “Latin Fathers” exhibited discomfort with how the Vulgate translated John 20:17. Whereas the Greek uses a present imperative to suggest “ongoing or continuous activity, best translated as ‘do not keep holding me’, implying that Mary Magdalene was already touching Christ when he issued this warning,” the Vulgate flattened this nuance into the direct imperative, “do not touch me.” Vuille writes that early church fathers worried how the Vulgate’s rendition could introduce a misogynist reading of the text. Listen to what she writes.

“The Latin Fathers had already noted the stark contrast between Christ’s command to the Magdalene not to touch him and his ordering Thomas, just ten verses later, to reach with his fingers inside his wound (John 20:27). They recognized in the discrepancy between these two passages the potential for a misogynistic interpretation and strove to negate this possibility by establishing the prohibition as spiritual and not physical. Since Ambrose, most Church Fathers argue that the noli me tangere constitutes only a temporary rebuttal, which arises because the Magdalene had failed to immediately recognize Christ’s changed divine state. They support the interpretation by referring to the counterexample of Matthew 28:9, a pericope showing how the Magdalene and another Mary meet the risen Christ and touch his feet.”

Isn’t that interesting? As early as the 4th century (the time of Ambrose) clergy worried about the misogynist impact of scripture translations on the role of Mary Magdalene. Moreover, by the later Middle Ages, some clergy were convinced that the significant role played by Mary Magdalene in the life of Christ was being suppressed by the Vulgate’s translation of John 20:17. Vuille concludes that “resistant readings” of the noli me tangere episode by later medieval clergy and women like Margery Kempe “should be seen as reiterating a well-accepted and orthodox interpretation of the episode in the late medieval religious context.” Medieval Christians preferred the Christ who allowed Mary Magdalene to touch him over the one who did not. (In another aside, and I’ll follow this in a later post, some medieval clergy in the central Middle Ages began using “noli me tangere” as a reason why women could not preach.)

Which brings me to Elizabeth (Libbie) Schrader. Recently Schrader, a PhD candidate in Early Christianity at Duke University, has argued that enough textual instability about Martha of Bethany exists in the story of the raising of Lazarus in early biblical manuscripts for us to question modern understandings of not only the Mary and Martha story but also the identity of Mary Magdalene. Instead of Martha proclaiming that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God, in Luke 11:27, what if it was Mary of Bethany who said this? What if, as Schrader posits, Mary of Bethany is the same woman as Mary Magdalene? That would mean one of the most important figures in the life of Christ–who stood with him at the crucifixion and resurrection, traveled with him and monetarily supported his ministry, became the first to see his resurrected body and carry the good news to the apostles, and gave the only confession of faith recognizing Jesus as the Christ to parallel the confession of Peter’s–was actually one woman: Mary Magdalene. As Schrader explains, “Martha is added as a way of diminishing Mary Magdalene and confusing her presentation.”

I am not a biblical scholar. I cannot evaluate the textual instability that Libbie Schrader has presented. But I find her argument attractive because it is so medieval. It reminds me of the medieval Mary Magdalene—both her more robust significance in the early ministry of Jesus as well as concerns about translations minimizing her importance. While a medieval perspective cannot weigh in on the manuscript evidence presented by Schrader, it does raise historical questions about how Christians for more than 1000 years believed Mary Magdalene played a more significant leadership role than more modern Christians (like my evangelical tradition) have allowed. Could John Mirk’s rendition of John 20:17 be more biblically faithful than we first suspected?

Just something to think about.

Till next time, y’all. Stay tuned as we continue discussing the faith of the medieval Mary Magdalene—or, as Diana Butler Bass framed her, the strong faith of Mary the tower.