My mother nurtured the vital habit of literacy in me from an early age. She daily read children’s books to me, and we frequented the public library, so I could participate in a story-hour for children. I have fond memories from childhood of floating in an innertube in our backyard pool and reading The Three Investigators, The Hardy Boys, or one of the many series of fantasy fiction books I enjoyed.

When I became interested in spiritual matters my sophomore year in high school, I exchanged a voracious appetite for profane literature for an interest in “godly reading.” I made a list of Christian books to read. I binged quite a bit of C. S. Lewis in those early days of spiritual growth. I also recall reading In His Steps by Charles Sheldon.

Yet, no book captured my imagination and resonated with my prior taste for fantasy literature like The Pilgrim’s Progress. I do not recall what edition of The Pilgrim’s Progress I read. I recollect that it was abridged and its English was modernized. To this day, The Pilgrim’s Progress is one of the most significant books I have read. It is on the short list of books I recommend to new believers. If you have not read it, I commend it to you. I recommend either the Penguin Classics version, edited and introduced by Roger Pooley; the Oxford World’s Classics version, edited with an introduction and notes by W. R. Owens; or the Audible adaption narrated by David Shaw-Parker.

The Popularity of The Pilgrim’s Progress

Among books published and printed in the English language, aside the Bible, The Pilgrim’s Progress scarcely has its equal. John Bunyan’s classic has never been out of print. The phenomenal success of this publication is only compounded by the conditions of its composition and the surprising gifts of its composer. Though it is one of the most read books in the English language, I will not assume you are familiar with this text or its author, so here is a brief summary on its background and publication.

John Bunyan (1628–88) served in Cromwell’s New Model Army during the English Civil War and married his first wife a couple years after the war’s resolution. Descended from a yeoman class family and trained as a tinker, Bunyan fell under deep conviction for his sin, while listening to the conversation of pious women in the backstreet of Bedford. A full account of his conversion story can be read from his autobiography, Grace Abounding to the Chief of Sinners (1666). He joined Bedford Free Church and under the mentoring of its pastor, John Gifford, he began to preach at the church and in the countryside. Having no formal education, he published his first publication in 1656, a polemic against Quakerism called Gospel Truths Opened. With the restoration of the Stuart monarchy in 1660, King Charles II committed to a policy that suppressed non-conformity. Even prior to the 1662 Act of Uniformity, Bunyan was arrested for transgressing the Conventicle Act of 1593. He remained in prison for twelve years until the king issued a declaration of indulgence in 1672. This indulgence increased religious toleration for non-conformists like Bunyan, who was released from prison that May.

During his long imprisonment, John Bunyan penned this classic allegory of the Christian faith, The Pilgrim’s Progress. It was printed in 1678 for Nathaniel Ponder at the Peacock in the Poultry near Cornhil in London. In the following years, its popularity and creative compositional style drew many readers to discuss and interpret its meaning. Others elaborated on the text and created aberrant revisions of the work.

In 1681, The Pilgrim’s Progress was printed for the first time in North America and translated and published for a Dutch audience. Since others had created unauthorized expansions and editions of his text, Bunyan found it necessary to expand his publication with a second authorized part in 1684.

The Plot of The Pilgrim’s Progress

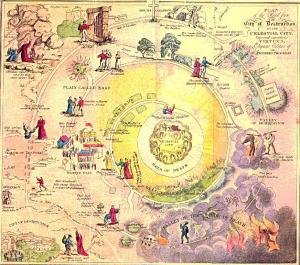

The original publication of The Pilgrim’s Progress followed the story of Christian, who upon reading from the book and listening to Evangelist, followed Evangelist’s instruction and fled the City of Destruction. He traveled to the Wicket Gate and received further instruction from the Interpreter. Pilgrim had his burden removed when he looked upon the Crucified One. The Shining Ones clothed him in new garments, gave him a scroll, and marked him on his forehead. He traveled along the Narrow Way, finding rest and relief at various stages. On his journey, he traveled with companions, encountered counterfeit pilgrims, and combated enemies, until he finally crossed the River of Death and reached the Celestial City.

The original publication of The Pilgrim’s Progress followed the story of Christian, who upon reading from the book and listening to Evangelist, followed Evangelist’s instruction and fled the City of Destruction. He traveled to the Wicket Gate and received further instruction from the Interpreter. Pilgrim had his burden removed when he looked upon the Crucified One. The Shining Ones clothed him in new garments, gave him a scroll, and marked him on his forehead. He traveled along the Narrow Way, finding rest and relief at various stages. On his journey, he traveled with companions, encountered counterfeit pilgrims, and combated enemies, until he finally crossed the River of Death and reached the Celestial City.

Michael Davies, in The Oxford Handbook of John Bunyan, remarks that one reason for the popularity of The Pilgrim’s Progress is Bunyan’s innovative technique to integrate Scripture into allegory. He comments:

Like an immersive virtual world, everything we see rendered imaginatively upon its pages—its landscapes, conversations, and people, as lifelike as they appear to be at times—is constructed from the informational building blocks of Scripture. This is a text programmed, as it were, in biblical ‘code’. Reading The Pilgrim’s Progress can, then, be like walking through the Bible itself: artfully rearranged and homiletically expounded; disguised as fiction but revealed as ‘Truth’ by characters who encounter scriptural quotations as objects to be held or beheld and who, like figures in Puritan guidebooks, address us ‘Dialogue-wise’, at times as imitations of humanity and at others as animated concordances (249).

The second part of The Pilgrim’s Progress picks up the story of Christiana and her children. When Christian flees the City of Destruction, he abandoned his wife and children. Some scholars have connected this plot line to a parallel in the real life of John Bunyan, whose wife and children had to support themselves for a dozen years while he languished in prison. Christiana is accompanied on her journey with Mercie and other travel companions. Most notable among them is their escort Great-Heart.

In her contribution to The Oxford Companion of John Bunyan, Margaret Olofson Thickstun provides an incisive analysis of the cultural and gender dynamics within the second part of Bunyan’s tale (308–24). She demonstrates how Bunyan offered a major corrective in his second part. In part one, Christian’s journey is emblematic of the individual experience of conversion and sanctification. Part two’s corrective emphasizes how the pilgrimage to the Celestial City is best done in community. Great-Heart fulfills the role of a pastor guiding a church to the Celestial City. Throughout part two, Bunyan focused more attention to the existence of house churches at places of respite and the refreshment pilgrim’s experienced in Christian community.

The role of women and children in the pilgrimage fit within the cultural dynamic of Puritan patriarchy and the English Common Law system of Coverture. Though the plot development revolves around Christiana and her children being reunited with Christian at the Celestial City, she and her children function as the supporting cast to the male stars. It’s these noble male pilgrims: Great-Heart, Valiant-for-Truth, and Stand-Fast, who stand out in the narrative, while weaker members of the group like Ready-to-Halt, Feeble-Mind, Despondency, and Much-Afraid play foils to the quintessential male figures of the group.

Margaret Sönser Breen suggests that the text emphasizes an oral culture rather than a literate culture for women. Throughout part two, Scripture is mediated by the men of the party. These men guide the women, who are weaker in frame and given to fancy. Kathleen M. Swaim’s interpretation of the second part masterfully conveys the tropes of domesticity and female subordination. Her work, Pilgrim’s Progress: Discourses and Contexts, situates the scholarship of Puritan femininity from Amanda Porterfield and Laurel Thatcher Ulrich within the specific case of The Pilgrim’s Progress.

The Portability of The Pilgrim’s Progress

These two parts of The Pilgrim’s Progress have been edited, abridged, translated, and adapted in hundreds of ways and for multiple mediums for nearly 350 years.

Isabel Rivers tracked the print story of this work during the eighteenth-century in her Vanity Fair and the Celestial City: Dissenting, Methodist, and Evangelical Literary Culture in England 1720–1800 (see especially 136–44). This story involves the calvinistical and methodistical contest waged through a print war of editions of The Pilgrim’s Progress. Rivers recounts how various editors bowdlerized the text to reflect their own theological inclinations concerning the doctrine of justification.

This contest was initiated by John Wesley. Wesley has been rightly credited as the organizer of revivalism in the eighteenth century, but perhaps not enough credit has been attributed to him for being a print genius of revivalism. His network of pastor-colporteurs and his ability to abridge texts into affordable tracts, for mass public consumption, spread a hunger for godly literacy and revival throughout the English-speaking world.

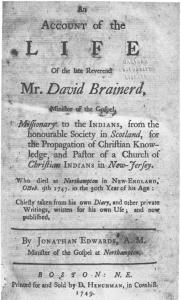

Isabel Rivers makes a notable connection between two great works in the Christian tradition that Wesley championed with wide print circulation. If Wesley believed The Pilgrim’s Progress was a significant text for stimulating the spiritual lives of everyday Christians, he believed The Life of David Brainerd was the signal text for stimulating itinerant preaching ministers and global missions. Rivers observes the magic behind the Life of David Brainerd is how he portrayed his spiritual journey as a pilgrim. Brainerd’s published diary provided a concrete example of Bunyan’s allegory. Rivers says, “The importance of Brainerd for Wesley and his preachers, which went beyond his importance for Edwards, was that he was an itinerant: he was a literal stranger and pilgrim who resisted the temptations of place, possessions, and family” (203).

Isabel Rivers makes a notable connection between two great works in the Christian tradition that Wesley championed with wide print circulation. If Wesley believed The Pilgrim’s Progress was a significant text for stimulating the spiritual lives of everyday Christians, he believed The Life of David Brainerd was the signal text for stimulating itinerant preaching ministers and global missions. Rivers observes the magic behind the Life of David Brainerd is how he portrayed his spiritual journey as a pilgrim. Brainerd’s published diary provided a concrete example of Bunyan’s allegory. Rivers says, “The importance of Brainerd for Wesley and his preachers, which went beyond his importance for Edwards, was that he was an itinerant: he was a literal stranger and pilgrim who resisted the temptations of place, possessions, and family” (203).

Isabel Hofmeyr’s The Portable Bunyan continues the story of the global spread of The Pilgrim’s Progress by recounting its translation and distribution throughout Africa in the nineteenth century. She argues that the book’s portability lies in its folktale like qualities and its capacity to function as both godly literature and magical fetish for Africans. In other words, it’s a text that thrived cross-culturally because of its qualities to syncretize with pre-existing cultural values in Africa. Hofmeyr asserts, “It was not so much a book as an environment, a set of orientations, a language, and a currency shared by most evangelicals. The evangelical energy that drove the dissemination of The Pilgrim’s Progress ‘at home’ simultaneously led to the book’s propagation and translation in other parts of the globe” (61).

Biblical Potency, Cultural Fluency, and Fluidity of Pilgrim History

In my last essay, I adapted the theological prolegomena of Franciscus Junius in order to cast a vision for pilgrim history. This essay has presented the popularity, plot, and portability of The Pilgrim’s Progress to exhibit how the idea of pilgrim history has a similar potential for widespread circulation and reception. The elements that distinguished John Bunyan’s creative allegory as a Christian spiritual classic are vital components of pilgrim history.

The Pilgrim’s Progress possessed biblical potency for its readers. Scripture came alive to its readers through vivid, figural similitude. Readers had to possess some level of biblical fluency to interpret the story’s meaning, and its creative rendering of Scripture whet reader’s appetites for Holy Writ. Since Christian history is the history of the development of Scriptural interpretations, pilgrim historians must possess a savvy fluency of Scripture.

However, a pilgrim historian must also distinguish biblical scripts from cultural scripts. Pilgrim historians must be deft and fluent in biblical and cultural exegesis. They must rightly divide between the Word of God and the world that has been constructed by men.

John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress reflected cultural values of Puritan patriarchy that confined women to a world of domesticity. He would have been shocked by Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women, who pilgrimaged as giant and dragon slayers from the basement to the attic. Sadly, our modern film dramatizations have not faithfully depicted Alcott’s ample allusions and appropriation of The Pilgrim’s Progress. And it is not happenstance that the skilled pilgrim historian, Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, published a cultural and social history of pious women in New England under the same title of Louisa May Alcott’s sequel, Good Wives.

John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress reflected cultural values of Puritan patriarchy that confined women to a world of domesticity. He would have been shocked by Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women, who pilgrimaged as giant and dragon slayers from the basement to the attic. Sadly, our modern film dramatizations have not faithfully depicted Alcott’s ample allusions and appropriation of The Pilgrim’s Progress. And it is not happenstance that the skilled pilgrim historian, Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, published a cultural and social history of pious women in New England under the same title of Louisa May Alcott’s sequel, Good Wives.

Thankfully, with their fascination for Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress, historians like Ulrich, Porterfield, Rivers, Hofmeyr, Swaim, Breen, and Thickstun long have been blazing a trail for pilgrims. These historians have devoted time and energy into distinguishing when the Bible speaks and when men speak.

The Pilgrim’s Progress functioned as a culturally adaptable and fluid text that has possessed a portability, which spans time and space. Unlike Bunyan’s Great-Heart, who could be none other than a male pastor, women readily function as pilgrim historians. Women historians stopped being sidelined and silenced long ago.

Sadly, I still encounter women, who earnestly believe they have to function like a submissive and subordinate Christiana. I also come across men, who follow the fiery conviction, that only men can be Great-Hearts in the fields of history and ministry.

We need more women set free to guide other pilgrims on a journey through time and space. We need women who employ the Sword of the Spirit to reveal the genuine intentions of Talkative’s heart. We need women who navigate pilgrims along the narrow way between the deep ditch and the quagmire, through Vanity Fair, and to the Celestial City. And we need more men to encourage, welcome, and validate our sisters, who are skilled, equipped, and ready to guide pilgrims through history.

The Anxious Bench will continue to champion these values in years to come.