I have often taught courses on Christian history, and on Global/World Christianity. There is one resource that I have found extremely useful, and it has the virtue of being a quick read. I offer it here in the hope that it might be of practical use. In a short space, it is perhaps the clearest explanation of why European and American Christians launched missionary ventures, why men and women risked their lives to go on mission, and how missions overlap inextricably with empires. It is, in a sense, a great project in excavating the intellectual and spiritual archaeology of a bygone religious age.

The text is “The Missionary” by Charlotte Brontë (1816-1855), most famous for writing Jane Eyre (1847). That novel contains a scathing picture of St. John Rivers, whose life’s ambition is to be a missionary, and he has to find a wife to share his dream. But he is a distinctly cold-hearted Christian, even reptilian. Charlotte Bronte was the daughter of an Anglican clergyman (and would later be married to another), and she was obviously thinking a great deal about missions and missionaries. In 1846, she published the poem that I am now describing, which offers a picture very different from that of St. John Rivers.

“The Missionary” tells of a man setting out on a venture that involves severing all his English roots:

PLOUGH, vessel, plough the British main,

Seek the free ocean’s wider plain;

Leave English scenes and English skies,

Unbind, dissever English ties.

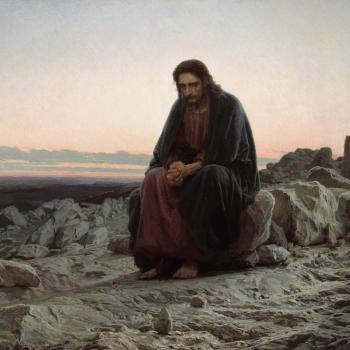

He has lost and forfeited all, including the love of his life. As he knows from the Bible, he cannot yield to the temptation of turning back: did Christ do so in the Garden of Gethsemane? The mission will likely cost his life, through disease or even martyrdom. We should always recall that prior to modern times, these were, for many, quite literally suicide missions, above all in Africa. Hmm, Suicide Missions – that would be a great title for a book on the missionary experience in that era.

So why is he going? Why, to storm the gates of Hell: nothing less.

This for me is why the poem is so useful in teaching. A typical US college class today has a favorable or even idealized view of non-Christian religions. So why bother with Christian missions at all? It might be nice to bring the Christian message, and to work for social improvement, but there is little sense of urgency. Those faiths are not bad of themselves – too obvious a point to be worth making.

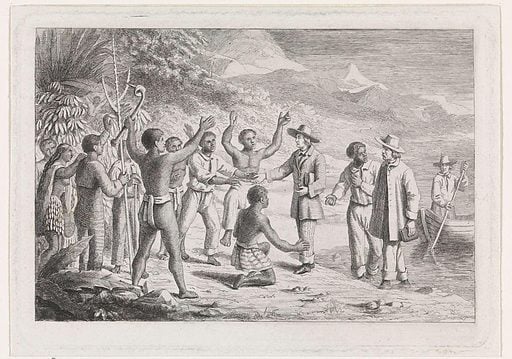

But now look at the 1840s, and the attitudes that Charlotte Bronte is representing, very faithfully, in her poem. Why do I go, asks the missionary? Because those pagan or heathen faiths are literally of the Devil. Beyond their raw spiritual evil, they are also associated with the worst kinds of social and political exploitation that were such a central focus of liberal activism in Europe at this time. They were tyrants and brutal exploiters in this world and the next. England, in contrast, is a Christian society, destined to rescue and elevate those people.

This is an extraordinarily difficult idea to convey today, but in the 1840s, there was an unquestioned and totally non-ironic belief that some states and societies were simply more advanced and superior to others. Moreover they had a moral and religious obligation to share the cultural and spiritual wealth – to spread education, literacy, and human liberation, to elevate and empower the weak, especially women. It’s a couple of years later, but the Great Exhibition of 1851 proclaimed the absolute superiority of British technology, culture, and civilization. At every stage, religion and culture intersected.

In a single package, Christianity brought salvation, modernity, and liberation. Or so it was firmly believed at the time.

Again, that is a paternalistic and benevolent vision of empire that will be utterly foreign to modern students, and this poem does a great job of explaining that concept. Note the language of tyrants and slaves, and how perfectly that meshes with the Abolitionist spirit of the 1840s. It might be a tough concept to get over today, but very similar impulses drove anti-slavery Abolitionism and those global missions, which were so intimately bound up with empire and imperialism.

By the way, that vision of Christian empire was very new to the English scene around this time. Before 1820 or so, the British in India had no interest at all in conversion, and if anything they were themselves tempted to follow Hindu and Muslim ways. After that point, a new evangelical Christian approach became ever more dominant.

Also important are the different regional emphases of missions. According to the stereotype, Africans were simply primitive, but Asians – particularly Indians – were subject to evil kings and emperors, working closely with similarly diabolical priests. If you ever saw something like the 1939 film Gunga Din, you get an excellent idea of those stereotypes of “Oriental” religious fanaticism. In actual history, those images were vastly augmented following the Indian Mutiny of 1857. Naturally, such stereotypes offered wonderful opportunities for framing anti-imperial rebels and anti-colonial resisters generally.

One critical theme here might seem counter-intuitive. Just where does our imaginary missionary get his very hostile ideas of Eastern religion, and chiefly Hinduism? In fact, Charlotte Bronte is drawing very heavily on anti-Catholicism, which by this point had centuries of experience in denouncing “priests, whose creed is Wrong, Extortion, Lust, and Cruelty.” As any American historian knows, anti-Catholicism was rampant in American cities of the 1840s and 1850s, when quite spectacular inter-communal riots were commonplace: Philadelphia in 1844 offered a nightmare example. In England, this was the time of the Tractarians and the Oxford Movement, which seemed to be a Papal Trojan Horse for the subversion of English society and faith. Fears reached new height with the conversion of John Henry Newman in 1845, less than a year before the publication of “The Missionary.” Pretty much every word of the critique in the poem could be applied unchanged to Protestant views of Ireland or Italy. That radical anti-clericalism, with its florid attendant mythologies, transferred easily to the Orient.

Another key idea to explain here is that of redemption, or salvation. Many Western Christians today have little time for the idea that there is no salvation outside the church, and still less that Hell is any kind of reality. For an evangelical of the 1840s, they had been saved by Christ’s blood, and that gave them an absolute obligation to share that blessing, even (again) at the cost of their lives.

Definitely use the whole poem in teaching. It isn’t long. But let me here quote some illustrative portions. Here, the missionary is contemplating his (Indian) destination, and its spiritual horrors:

And even when, with the bitterest tear

I ever shed, mine eyes were dim,

Still, with the spirit’s vision clear,

I saw Hell’s empire, vast and grim,

Spread on each Indian river’s shore,

Each realm of Asia covering o’er.

There, the weak, trampled by the strong,

Live but to suffer–hopeless die;

There pagan-priests, whose creed is Wrong,

Extortion, Lust, and Cruelty,

Crush our lost race–and brimming fill

The bitter cup of human ill;

And I–who have the healing creed,

The faith benign of Mary’s Son;

Shall I behold my brother’s need

And, selfishly, to aid him shun ?

….

Dark, in the realm and shades of Death,

Nations and tribes and empires lie,

But even to them the light of Faith

Is breaking on their sombre sky:

And be it mine to bid them raise

Their drooped heads to the kindling scene,

And know and hail the sunrise blaze

Which heralds Christ the Nazarene.

I know how Hell the veil will spread

Over their brows and filmy eyes,

And earthward crush the lifted head

That would look up and seek the skies;

I know what war the fiend will wage

Against that soldier of the cross,

Who comes to dare his demon-rage,

And work his kingdom shame and loss.

Yes, hard and terrible the toil

Of him who steps on foreign soil,

Resolved to plant the gospel vine,

Where tyrants rule and slaves repine;

Eager to lift Religion’s light

Where thickest shades of mental night

Screen the false god and fiendish rite

….

Hurling hell’s strongest bulwarks down,

Even when the last pang thrills my breast,

When Death bestows the Martyr’s crown,

And calls me into Jesus’ rest.

Then for my ultimate reward–

Then for the world-rejoicing word–

The voice from Father–Spirit–Son:

” Servant of God, well hast thou done !”

Trust me, “The Missionary” gets some excellent class conversations going.