I don’t often dip into my archives and reprise a post. But since the U.S. Congress may (underline may) be on the verge of making Daylight Saving Time a permanent fixture, I thought the post I originally wrote for “falling back” might be actually be more helpful now that we may have “sprung forward” for good. It’s been lightly edited.

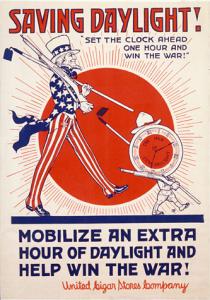

Daylight Saving Time (DST) is not the farmers’ fault, explained the New York Times last November. On the contrary, DST is “a disruptive schedule foisted on them by the federal government.” And it’s not really Ben Franklin’s fault either. Instead, the story of daylight saving starts with railroad companies — who standardized North American time zones in 1883, to avoid the problem of having locally-determined “sun times” that varied from stop to stop along their routes. Once that had happened, “it wasn’t long until Franklin’s idea for daylight saving was refashioned for the industrial world” — though it took the impetus of an industrial war. At the end of April 1916, Germany moved its clocks forward in order to maximize productivity and minimize fuel consumption in war industries; its enemies in World War I soon followed suit and embraced what the Times then called “the Kaiser’s trick hour.”

In June 1917, two months after the U.S. entered the war, the U.S. Senate voted for a bill that would both make official “railroad time” and move American clocks ahead an hour for over six months of “summer time.” But the House of Representatives didn’t sign off on the Standard Time Act until the following March, then Congress overruled Woodrow Wilson’s veto in August 1919 and eliminated daylight saving. A year-round daylight saving measure called “War Time” returned during WWII, but it wasn’t until 1966 that the U.S. moved more permanently to something like the current system.

Why was the U.S. relatively slow to adopt and then retain daylight saving? At least part of the answer makes me at least a bit more certain that Everything Has a Religious History.

Of course, Christians being late or early to church because of daylight saving is more than a century old now. America’s first attempt at DST went into effect on March 31, 1918 — Easter Sunday — so the National Daylight Saving Association encouraged churches to “ring their bells more lustily than usual” to call the confused faithful to worship. “The attendance at the churches was reported as unusually large,” said the New York Times, “but many of the churchgoers were an hour behind the new time.” Meanwhile, Catholic churches in York, Pennsylvania simply waited until noon to change their clocks, and kept morning masses at their usual times.

But it’s not just confusion about the timing of worship that makes religion relevant to the history of time in this country and others.

When the standardized zones of “railroad time” went into effect in the fall of 1883, a minister in Maine celebrated the change. “There is no practical difficulty in having school time, church time, shop time and business time conform to railroad time,” wrote Rev. H.G. Wood in the Portland Daily Press. “The advantages of uniformity in local time is greater than we can now appreciate. Let this be once established and the people could not be persuaded to return to the confusion that now exists.” But not all Christians agreed. “Some clergy,” reports Ian Bartky, “argued that the local time of their region was God’s time and that the new time was a falsehood—it was not based directly on the Earth’s rotation.”

And daylight saving? When it went into effect in 1918, The American Ecclesiastical Review shrugged that

there were always differences between true time and legal time… The change to the “new time” should… give rise to no difficulty or scruple, nor is there, so far as we know, any inclination among Catholics to sympathize with the Englishman who, when a similar law was passed in Great Britain, protested, in the name of public morality, against an Act “that would make all our clocks public liars”. We have adjusted ourselves quite naturally to the change and our duties and obligations as Catholics have not made it more difficult to do so.

But the “God’s time” refrain returned when Congress debated ending DST after the end of WWI. “Repeal the law and have the clocks proclaim God’s time and tell the truth,” thundered Rep. Ezekiel Candler (D-Mississippi), who wanted to undo the law he and nearly forty other legislators had voted against during the war. Another congressman, Illinois Republican Edward King, listed among DST supporters “the impractical, the Utopians, the theorists, political astrologers, medicine men, and advance agents of the millennium.” A citizen from Kansas City griped that “God knows more about time than President Wilson does,” in a letter that didn’t stop Wilson from vetoing the repeal not once, but twice.

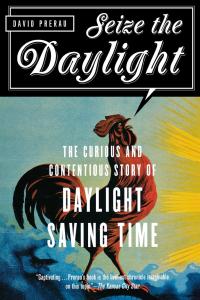

(By the way, it wasn’t just American Christians who had concerns about such innovations in timekeeping. David Prerau, from whose book on the subject I’ve borrowed several of my examples, notes that the post-WWI debate about daylight saving in Canadian provinces mirrored the arguments taking place across the border. In Quebec, for example, most churches called for a return to l’heure de Dieu.)

The fact that there were enough rural legislators to override Wilson’s vetoes in 1919 didn’t stop cities like New York from continuing daylight saving on their own. But it wasn’t until 1942 that a national DST plan returned, and it ended abruptly, less than a month after V-J Day. “We should abolish war time,” said Rep. Benton Jensen (R-Iowa) in August 1945, “and get back to God’s time.”

In the absence of federal standards, American timekeeping returned to its traditional variety. According to Michael Downing, most states kept some daylight savings — half for half the year, half for less — but twelve abandoned the practice altogether. And even then, differences persisted at lower levels of government. For example, one Kentucky writer recalled that, by 1960, “Railroad Time… had become God’s Time and Daylight Saving Time was known as Railroad Time…. One would find that while the county seat was on Railroad Time, the county was on God’s Time. Or… the county judge was operating on Railroad Time, but the County Clerk was conducting business on God’s Time.”

Prerau tells the story of one preacher from Indiana, who complained to a government official that “half my congregation favors daylight time, and the other half, standard time. When should I open my church?”

“Use your own judgment,” replied the official. “I just did that,” said the pastor, “and lost half my congregation.”

By 1964, one congressman complained of the “horological nightmare now encumbering our country.” (A year later, Minnesota’s Twin Cities managed to have different times for two extraordinarily confusing weeks, after St. Paul decided to start daylight saving before Minneapolis and the rest of the state!) At the same hearing, Rep. Kenneth Gray (D-Illinois) declared that “standard time is God’s time. Let’s just revert to it.”

Some senators opposed to reviving DST actually put up signs on their doors reading “This office operates on God’s time,” but Gray’s version of that phrase prevailed. After a long debate over the length and placement of hour-ahead period, the Uniform Time Act went into law in April 1966, standardizing time zones and adopting daylight saving for good. When there was a movement to extend DST by three weeks in 1985, notes Frerau, opposition continued to come from predictable quarters, including farmers and “religious fundamentalists who continued to feel that DST was an offense against nature.” But President Reagan signed the extension into law a year later.

Since then, I can’t say I’ve noticed significant religious antipathy to daylight saving, even when it expanded by a few more weeks in 2007. In fact, the current attempt to make DST a year-round fixture has been championed by a Christian conservatives, Florida senator Marco Rubio. Since he succeeded in convincing all of his fellow senators to adopt permanent daylight saving, the main objections have come from sleep scientists, not pastors — who may appreciate not having to remind congregants twice a year about getting to church on time. (Though that does eliminate desperate an occasional source of sermon illustrations.)

Since then, I can’t say I’ve noticed significant religious antipathy to daylight saving, even when it expanded by a few more weeks in 2007. In fact, the current attempt to make DST a year-round fixture has been championed by a Christian conservatives, Florida senator Marco Rubio. Since he succeeded in convincing all of his fellow senators to adopt permanent daylight saving, the main objections have come from sleep scientists, not pastors — who may appreciate not having to remind congregants twice a year about getting to church on time. (Though that does eliminate desperate an occasional source of sermon illustrations.)

But the “God’s time” argument might be worth remembering on at least two counts. First, as a reminder that what they once regarded as a human usurpation of God’s authority or a rash rejection of an eternal truth can eventually strike Christians as being utterly non-controversial.

Then second, as a reminder that there was a time when big business didn’t seem like a good partner for conservative Christians. In 1883, says Smithsonian curator Carlene Stephens (in the New York Times article I started with), evangelical Christians argued that “time came from God and railroads were not to mess with it.” By the time daylight saving came up for debate in 1918-19, railroad companies were generally opposed*. But most of DST’s most powerful advocates were in it for profit: industrialists who wanted to cut fuel costs, department store owners who wanted more shoppers, baseball owners who wanted more ticket buyers, and the half million members of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce who endorsed DST at their 1917 convention. At least some of them must have been golf ball manufacturers, whose sales rose 20% as the wealthy found themselves with an extra hour of daylight.

Joining the call for DST’s repeal in 1919, Rep. Thomas Schall (R-Minnesota) called it “a pet of the professional class, the semileisure class, the man of the golf club and the amateur gardener, the sojourner at the suburban summer resort.” Lamenting the effects on farmers in his home state, he complained that “it is not American to force on the worker a penalty to pay for the pleasure of another class.” I don’t know anything about Schall’s religious beliefs, but I’ll conclude with the biblical allusion he used to embellish his rhetoric: “Joshua commanded the sun to stand still, and it obeyed, but the Democratic Party out-Joshuaed Joshua by moving the sun an hour forward.”