I love spending time in the American southwest. Many years ago, I was talking with a New Mexico historian who introduced me to the concept of the Genízaros, people of mixed Native American heritage who followed aspects of the Hispanic lifestyle. (More on exactly who they were below). But at the time, I had one simple question: why are we talking Turkish?

Empires play a critical role in spreading ideas across vast swathes of territory. Imperial servants or officials might encounter an idea or institution or technology in one part of the realm, and they take it with them when they are transferred half-way across the world. This is commonly how religious motifs are carried far afield – and sometimes whole religions. Also, empires have institutional memories, so that experiences from the distant past can linger on to affect later generations. And this brings me neatly to those Genízaros, who can only be understood as relics of successive empires, and their interactions.

Through the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, New Mexico was home to large numbers of these people. Genízaros, or their parents, had been captured or traded, and they occupied a curious status of semi-slavery. I quote a great (and gorgeously illustrated!) photo essay by Russell Albert Daniels:

Funded by the Spanish Crown, the Spanish first abducted and then later purchased war captives from surrounding tribes. Those “ransomed” were primarily from mixed tribal heritage, including Apache, Comanche, Kiowa, Navajo, Pawnee, and Ute. The colonists took these individuals to their households, where they were taught Spanish and converted to Catholicism. They were forced to work as household servants, tend fields, herd livestock, and serve as frontier militia to protect Spanish settlements.

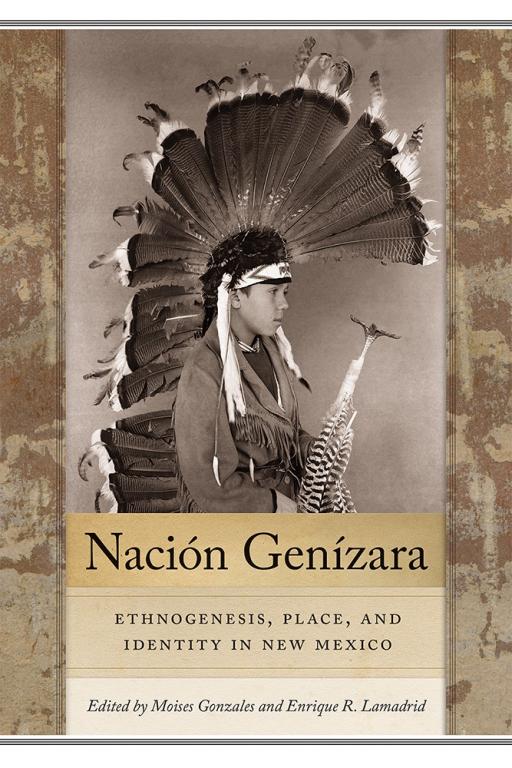

Genízaros could rise socially through military careers, and sometimes they led Spanish colonization of new areas. They became numerous, and by 1800 they represented a sizable share of the population of New Mexico. Their history and survival is addressed in a fascinating collection of essays called Nación Genízara, edited by Moises Gonzales and Enrique R. Lamadrid (University of New Mexico Press, 2019). The famous pueblo of Abiquiú was a Genízaro settlement.

But who were those Genízaros?

Genízaro is an odd word, which is actually borrowed from half-way across the planet. It is a straightforward version of the Turkish janissary (yeni-cheri, “new soldiers”), mediated through the Italian form giannizzero. “Janissary” was one of the most feared terms in early modern Christian Europe. From the fifteenth century, the Ottoman Empire levied a tribute of its conquered Christian peoples, who were forced to supply young sons to state service. Those sons were required to convert to Islam, and they received a strict military training. As adults, these janissaries represented the most fanatical and skilled imperial soldiers, who could rise to wealth and fame, although they remained slaves. The Janissaries led the Ottoman advances against Europe’s Christian powers. Between 1500 and 1700, Islam’s janissaries represented a constant nightmare for the Habsburg states, of Spain and the Holy Roman Empire. In the 1680s, those armies came close to taking Vienna and conquering Central Europe.

Genízaro is an odd word, which is actually borrowed from half-way across the planet. It is a straightforward version of the Turkish janissary (yeni-cheri, “new soldiers”), mediated through the Italian form giannizzero. “Janissary” was one of the most feared terms in early modern Christian Europe. From the fifteenth century, the Ottoman Empire levied a tribute of its conquered Christian peoples, who were forced to supply young sons to state service. Those sons were required to convert to Islam, and they received a strict military training. As adults, these janissaries represented the most fanatical and skilled imperial soldiers, who could rise to wealth and fame, although they remained slaves. The Janissaries led the Ottoman advances against Europe’s Christian powers. Between 1500 and 1700, Islam’s janissaries represented a constant nightmare for the Habsburg states, of Spain and the Holy Roman Empire. In the 1680s, those armies came close to taking Vienna and conquering Central Europe.

But how on earth did “janissaries” get from the Ottoman world to New Mexico? Blame the empires. Janissaries originated in one empire, in confrontation with another, the Habsburg realm. But other Habsburgs ruled the mighty Spanish Empire, which sprawled over the New World and the Pacific. Through the centuries, Spanish and Austrian Habsburgs had regularly cooperated in fighting the Turkish foe. They knew their common enemies.

Around 1700, the Spanish found themselves on yet another remote frontier, fighting such ferocious enemies as the Apache and Comanche. It took no great effort for them to comprehend the situation in familiar terms. Whatever they called themselves, however different their technologies, those enemies were essentially identical to the traditional foe that Christians knew from the Mediterranean world, namely the Turks. Did Turks and Apaches not follow the same religion, which was pagan devil-worship?

To fight the Indian foe, then, the Spaniards resorted to tried and true methods from the European battlefield, which meant using slave-soldiers — American janissaries, or Genízaros.

At first glance, the idea that Native Americans were somehow parallel to Muslim Turks seems eccentric to the point of demented. Yet without appreciating that parallel — at least in the minds of the imperial conquerors — we can scarcely understand the mindset of the Spanish and Portuguese who conquered and settled the New World.

For centuries before 1492, the Christians of the Iberian peninsula had a special devotion to St. James the Apostle, Santiago, who was (and is) depicted as a mounted warrior riding down Muslim foes. Santiago! was the battle-cry of the Christian knights who by 1492 completed the conquest of the whole region. Barely thirty years afterwards, the descendants of those conquerors found themselves fighting new pagan enemies in Mexico, where once again the Conquistadors charged into battle shouting Santiago!

Empires have long memories, and they carry them across the world.

Going marginally off topic, there is a lovely recent history of other people who existed on the margins between empires, nations, and cultures in the American southwest in the nineteenth century, and who also spent a great deal of time negotiating their identities. The book also has an irresistible title: James Bailey Blackshear and Glen Sample Ely, Confederates and Comancheros: Skullduggery and Double-Dealing in the Texas-New Mexico Borderlands (University of Oklahoma, 2021).