I love Advent. It is the season in the church calendar that I have observed the longest, which is to say for many years before I joined a liturgical church. For the unfamiliar, the weeks starting four Sundays before Christmas have historically been set apart as a time to contemplate and prepare for not only the commemoration of Jesus’s first coming in Bethlehem, but also his future second coming at the end of this age—and the ways that Christ comes in ever greater measure to us today by Word, Sacrament, and Spirit.

As such, it leans into themes like waiting and longing (for the nine months of pregnancy, for the day and hour that we know not, for spiritual breakthrough). It stares present darkness and evil straight in the face but also actively kindles hope in God’s deliverance. Grittier fare than candy canes and gingerbread men. I love these as much as the next person, and they can be aids to rejoicing in hope, but by themselves they don’t satisfy.

Maybe my love of Advent came from being American: in the United States, we functionally celebrate Christmas during all of December and I’m the sort of person who seeks meaning in practices. So I started learning more about how the church has historically thought about the time leading up to Christmas. And maybe it’s because, as a single person, 100% festive communal celebration all the time just didn’t jibe with my experience. I was drawn to the more solitary, quiet, introspective aspects of the season. The small but brilliant lights in the darkness.

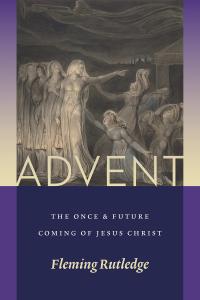

Episcopal priest Fleming Rutledge presents an excellent brief history of how Christians, particularly in the West, came to think about the weeks before Christmas in the introduction to her sermon collection Advent: The Once & Future Coming of Jesus Christ. Her passion for revitalizing the church’s commemoration of the season has earned her the appellation “St. Fleming of Advent” (xviii). Here she is on Advent’s historical evolution:

Episcopal priest Fleming Rutledge presents an excellent brief history of how Christians, particularly in the West, came to think about the weeks before Christmas in the introduction to her sermon collection Advent: The Once & Future Coming of Jesus Christ. Her passion for revitalizing the church’s commemoration of the season has earned her the appellation “St. Fleming of Advent” (xviii). Here she is on Advent’s historical evolution:

The origins and development of the Advent season are less well understood than we might wish. There were varying emphases and customs in differing parts of Christendom in the fourth and fifth centuries, leaving us with a mixed picture that continues today. It has been tempting for local churches in recent times to seize upon notions of Advent observance in the early centuries to support the idea that it has always been essentially a season of preparation for Christmas. However, there is evidence to show that as late as the fourth century, a December season of penitence and fasting had no clear relationship to Christmas, at least not in Rome. By the seventh century, however, the Advent-Christmas connection was well-established, and Advent has been observed as a penitential season, not unlike Lent, in preparation for Christmas up until the every recent past….[B]y the medieval period the essentially eschatological nature of the Advent season was fully established. Martin Luther, in particular, was remarkably attuned to the apocalyptic Advent language….In the medieval period, the Scripture readings for Advent were well established, and they were oriented only secondarily to the birth (first coming) of Christ; the primary emphasis was his second coming on the final day of the Lord. (3-5)

Though she serves in the mainline Episcopal church, Rutledge draws heavily from traditionalist Lutheran theology to critique and reform her own tradition. She praises how the Episcopal church has guarded and maintained historic Advent observance. But she fears it too often devolves into mere exhortations to be better and do better—about genuinely good things such as alleviating poverty, fighting racism, and showing hospitality. But without also preaching that Christ promises to redeem and empower us now and bring complete justice and righteousness in the end, exhortations result in either despair that we can’t do enough or smugness that we are doing more than others (27). So she elaborates:

Whereas Roman Catholic preachers [in the early modern period] continued to exhort those attending Mass to double up on their penitential practices during advent, Lutheran preachers focused on proclamation of the undeserved grace of God—evangelistic sermons rather than hortatory ones….Related to the second coming, which Jesus repeatedly says will come by God’s decision at an hour we do not expect, is the Advent emphasis on the agency of God, as contrasted with the “works” of human beings. An exclusive emphasis on Advent as a season of preparation risks putting human endeavor in the spotlight for all four weeks of the season. All the Advent preparation in the world would not be enough unless God were favorably disposed to us in the first place…[hence] the theme of watching and waiting.” (4-5)

As I conducted my own research into the history of the Christian calendar over the last few years, I came to the conclusion not that it is the only way to observe time and grow in faith, but rather that it is a wise one, the product of Christians in many times and places reflecting on how to live into the breadth of Christ’s work during his life on earth and his continuing work in the church.

In the West, the church year starts with Advent—commemorating both the conclusion of this world in the second coming, and the beginning of the Christian narrative in the first—and proceeds through Christmas, Epiphany (the coming of Jesus made public, and continuing through his ministry), Lent (a penitential season focused on his preparation for crucifixion for our sins), his death on Good Friday, his resurrection on Easter, Ascension into heaven, and the pouring out of the Holy Spirit on the church at Pentecost. Then follows “ordinary time,” when the narrative continues through the second half of the year as the church, the Body of Christ on earth today, goes about its daily work of evangelism, discipleship, mercy, and justice.

As Rutledge notes, the process of coming up with the calendar was messy and uneven and hence it is not celebrated in exactly the same way across all liturgical traditions, not to mention in every church within the same tradition! And that’s OK. If it were otherwise, we might be tempted to make it yet another human way to God rather than, like Christ, a gift through which we are invited to encounter God. The historical consensus that I find so life-giving is the pattern of fasting and feasting, and the opportunity to regularly lean into different aspects of the Christian life that our finitude requires experiencing in sequence.

And what makes Advent distinct from Lent—both “fasting” seasons before “feasting” seasons—is the emphasis not so much on personal repentance, though that is more than appropriate at any time. It’s the crying out with the psalmist, “How long, O Lord?” Confronting our disappointment, disillusion, frustration, even despair. And, like the psalmist, working through to “But I trust in your unfailing love.”

This has been quite the couple of years, in American society and in the American church. Injustices surrounding race and sexual abuse, an actual domestic political rebellion, and a global pandemic have been a lot to bear on their own, and for some more than others. Adding additional weight to this burden have been the fractures within churches along how best to respond. How long, O Lord, indeed.

This has been quite the couple of years, in American society and in the American church. Injustices surrounding race and sexual abuse, an actual domestic political rebellion, and a global pandemic have been a lot to bear on their own, and for some more than others. Adding additional weight to this burden have been the fractures within churches along how best to respond. How long, O Lord, indeed.

So for those looking to lean into Advent, here are a few of my favorite things: Anglican priest Tish Harrison Warren’s recent book Prayer in the Night: For Those Who Work or Watch or Weep exegetes a traditional Anglican nighttime prayer as a guide to processing the reality of the darkness and difficulty of this life from the standpoint of faith and hope in Christ.

Also, for many years I have loved a pair of “Christmas” albums by Over The Rhine: Snow Angels and Blood Oranges in the Snow. They call this music “Reality Christmas” but I realized this year that they are, in reality, “Advent” albums. The song “White Horse” from Snow Angels perfectly captures the connection between the first and second advents and the spirit of longing. It makes me cry, every time. How’s that for an endorsement of Christmas music?

But I’m crying because it is achingly beautiful. And it is cultivating that space for God’s beauty to break in that is the opportunity into which we are invited each December.