The first issue of Sojourners (originally called The Post-American) was published in the fall of 1971, which means that this progressive evangelical standard turns fifty this year. Happy birthday!

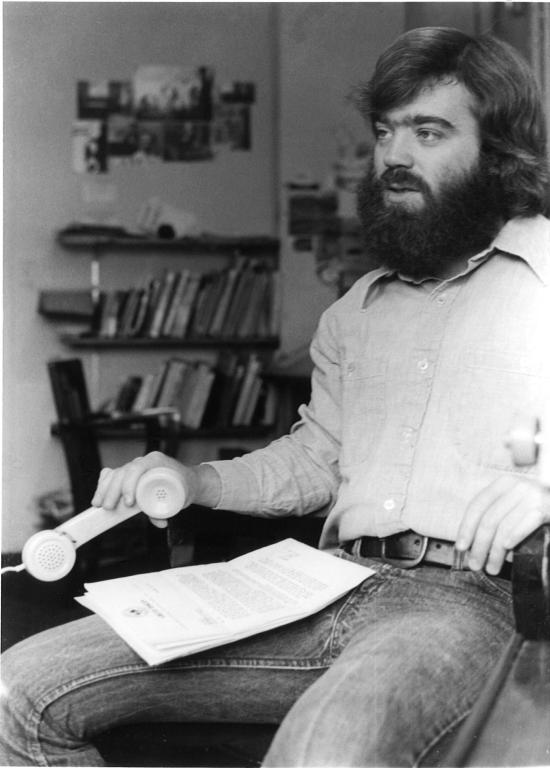

Though located in Washington, D.C., for the majority of its life, the magazine was actually launched in the Chicago suburbs by a group of Trinity Evangelical Divinity students, including provocateur Jim Wallis. A Michigan State University graduate with connections to Students for a Democratic Society, Wallis had started seminary the year before. He motored around the southern tip of Lake Michigan in his Ford Falcon, ready to combine his revived faith with a radical critique of American politics and international policy. Wallis intended to “take on the evangelical world with Jesus and the Bible.”

Though located in Washington, D.C., for the majority of its life, the magazine was actually launched in the Chicago suburbs by a group of Trinity Evangelical Divinity students, including provocateur Jim Wallis. A Michigan State University graduate with connections to Students for a Democratic Society, Wallis had started seminary the year before. He motored around the southern tip of Lake Michigan in his Ford Falcon, ready to combine his revived faith with a radical critique of American politics and international policy. Wallis intended to “take on the evangelical world with Jesus and the Bible.”

The young seminarian quickly incited the conservative campus into heated debate about the war in Vietnam. Every Wednesday at noon, students and faculty met for lunch and debate at The Pits, a small café in the basement of the administration building where polite discussion often spiraled into heated arguments between just war advocates and pacifists. A noisy student with red hair and a bushy red beard, Wallis was “the archetype of a prophet,” a classmate remembered, who often served as the lightning rod in these debates. [Be sure to click here from some priceless photos of a young Jim Wallis and his longhaired seminary friends.] His fellow students would “sit there with mouths agape getting really mad at him” as he charged Trinity with having departed from biblical ideals.

With unrelenting appeals to Scripture, the young firebrand worked hard on his classmates. Wallis ripped out all the pages in the Bible that dealt with money and poverty, leaving only a tattered shell remaining, to make his point that social justice mattered. While others in the New Left made their case using sociological arguments, Wallis “made it theological” and insisted on scriptural justification for arguments. This was a tactic that convinced disenchanted divinity students to rally around his leadership.

The “Bannockburn Seven,” named for the wealthy section of Deerfield where Trinity was located, rallied first against stringent campus standards. When the faculty rejected a 93 percent student vote urging the loosening of parietals, Wallis and his friends released a manifesto charging that the school “will become either a center of progressive evangelical thought, or a fundamentalist enclave of legalism, sell-out religion, and reactionary thought. The choice is yours.” They invited the Chicago Tribune to observe a mock funeral held in front of the administration building, where they played Taps, built a makeshift graveyard, and “buried student opinion.” They particularly targeted eminent evangelical theologian and dean of the seminary Kenneth Kantzer, who told protesting students seeking reform “outside the framework of legitimately elected student government” to consider themselves “not welcome.” Faculty, he reasoned, had come from the “greatest universities on earth, prepared to write volumes on the decisive theological issues of the day”; instead, they were getting “tied up for significant amounts of time debating whether visiting hours for girls should be from 3-12 or 4-11 on Saturdays and Sundays.”

The Bannockburn Seven, however, quickly broadened their agenda beyond campus rules to critique the evangelical non-engagement with broader social issues. Bob Sabath felt “deep alienation from the church,” telling a Milwaukee newspaper reporter that “I felt the evangelical church had betrayed me, betrayed itself. It was not dealing with those questions of racism, war, hunger.” In a “Deerfield Manifesto,” written in late 1970, the seminarians stated that the “Christian response to our revolutionary age must be to stand and identify with the exploited and oppressed, rather than with the oppressor.”

By the summer of 1971, Wallis and his compatriots had formed the People’s Christian Coalition (though they more often called themselves the “Post-Americans,” which was the name of the magazine they would soon edit) to address violence, race, poverty, pollution, and other “macro-ethical subjects.” They met regularly for prayer, Bible study, sociological study, celebrations called “God parties” (which always opened with a rendition of Three Dog Night’s “Joy to the World”), and demonstrations against the war. Under threat of expulsion and as the Coalition rapidly grew and took up more of their time, they finally stopped taking classes at Trinity. But their common “alienating seminary experience,” as Sabath put it, continued to bind them together. In early 1972, twenty-five of their Trinity classmates joined their intentional community, located initially in an apartment building in Rogers Park on Chicago’s north side and then in the impoverished Uptown area.

By the summer of 1971, Wallis and his compatriots had formed the People’s Christian Coalition (though they more often called themselves the “Post-Americans,” which was the name of the magazine they would soon edit) to address violence, race, poverty, pollution, and other “macro-ethical subjects.” They met regularly for prayer, Bible study, sociological study, celebrations called “God parties” (which always opened with a rendition of Three Dog Night’s “Joy to the World”), and demonstrations against the war. Under threat of expulsion and as the Coalition rapidly grew and took up more of their time, they finally stopped taking classes at Trinity. But their common “alienating seminary experience,” as Sabath put it, continued to bind them together. In early 1972, twenty-five of their Trinity classmates joined their intentional community, located initially in an apartment building in Rogers Park on Chicago’s north side and then in the impoverished Uptown area.

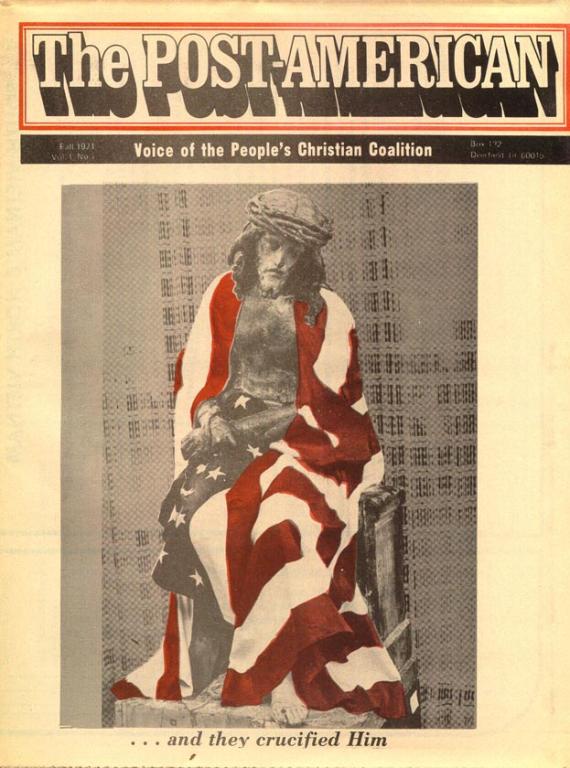

The seminarians’ most enduring legacy came from their tabloid, which featured a signature blend of evangelical piety and leftist politics. The first issue of The Post-American featured a cover of Jesus wearing a crown of thorns and cuffed with an American flag that covered his bruised body. America, the depiction implied, had re-crucified Christ. Inside, “A Joint Treaty of Peace between the People of the United States, South Vietnam and North Vietnam” declared that the American and Vietnamese people were not enemies and called for the immediate withdrawal of U.S. troops. The “American captivity of the church,” Wallis continued, “has resulted in the disastrous equation of the American way of life with the Christian way of life.”

For Wallis the publication of the Post-American’s first issue was a deeply spiritual moment. Having stayed up all night editing, returning proofs to the printer, and hauling stacks of freshly printed issues back to his small apartment, he paused in the early morning hours. He placed a copy on his bed, dropped to his knees, and began to pray. Strong feelings of “gratitude, expectation, and bold, confident faith” rushed over him as he reflected over the long journey that had led him to this point. “The gospel message that had nurtured us as children was now turning us against the injustice and violence of our nation’s leading institutions and were causing us to repudiate the church’s conformity to a system that we believed to be biblically wrong.”

It was an audacious declaration. And the Post-Americans proclaimed it widely. They distributed 30,000 copies of the first edition, printed with $700 in pooled money. They blanketed fifteen colleges and seminaries in the Chicago area and sold copies for 25 cents throughout Chicago. Within several months, they had sold 225 full subscriptions. The real growth potential, however, lay in the thousands of other disillusioned evangelical students across the country. They borrowed mailing lists and took their searing critique on the road in an attempt to awaken sleepy evangelical campuses and to startle big state universities. Wallis and Clark Pinnock, his mentor and a professor at Trinity, traveled to the University of Texas at Austin under the auspices of InterVarsity to preach and condemn the war on the streets. Another sixteen-day trip in spring 1972 took the Post-Americans to evangelical campuses, major universities, intentional communities, and churches in northern Indiana, lower Michigan, northern Ohio, central and eastern Pennsylvania, and up the east coast from Washington, D.C. to Boston. They brought copies of their magazine, distributed reading lists full of New Left writers, and offered free university courses in Christian radicalism, the New Left, women’s liberation, and racism.

They gained even more publicity when Mark Hatfield, a U.S. Senator from Oregon, and John Stott, Britain’s leading evangelical figure, endorsed them. Within two years, 1,200 people had subscribed to the Post-American; within five years, nearly 20,000. The Post-Americans had clearly tapped into a substantial market of angst-ridden evangelicals searching for authentic faith.

Through the 1970s, the magazine offered a steady diet of radical critiques of the American liberal establishment. Citing New Left voices Herbert Marcuse and Charles Reich, it offered economic critiques of unlimited growth. Keynesian economics, writers charged, merely justified corporate greed. The Post-Americans denounced Proctor and Gamble, Ford, AT&T, and Westinghouse for perpetuating the “liberal-industrial scheme” of unlimited economic growth. “We protest,” Jim Wallis declared in an exemplary critique of liberalism, “the materialistic profit culture and technocratic society which threaten basic human values.” Over one hundred articles on the poor and disenfranchised appeared in the Post-American from 1973 to 1978, many of them explicitly blaming consumer culture, big business, and the liberal scheme of consumption to stimulate the economy for creating economic stratification.

Through the 1970s, the magazine offered a steady diet of radical critiques of the American liberal establishment. Citing New Left voices Herbert Marcuse and Charles Reich, it offered economic critiques of unlimited growth. Keynesian economics, writers charged, merely justified corporate greed. The Post-Americans denounced Proctor and Gamble, Ford, AT&T, and Westinghouse for perpetuating the “liberal-industrial scheme” of unlimited economic growth. “We protest,” Jim Wallis declared in an exemplary critique of liberalism, “the materialistic profit culture and technocratic society which threaten basic human values.” Over one hundred articles on the poor and disenfranchised appeared in the Post-American from 1973 to 1978, many of them explicitly blaming consumer culture, big business, and the liberal scheme of consumption to stimulate the economy for creating economic stratification.

The magazine also objected to faith in science and to the “spirit-deadening assembly-line routine” of technology. Technology gave the “powers and principalities,” as Wallis called governments, corporations, and other brokers of power, an even more insidious means of wielding control over “the people” than traditional uses of power. One of their most compelling examples was infant formula. From all appearances it seemed like a technology that could help orphaned babies and mothers who didn’t have a milk supply. Instead, it led to costly dependence on American companies, intent only on increasing their consumer base and the reach of their economic empires. Given the need for clean water, sterilization, and the formula itself, contended the Post-Americans, offering classes on techniques of breastfeeding would be simpler and less disruptive to cultural norms. The ties between technology and big business led many New Leftists to despair about “the technocracy,” a term used with regularity among radical evangelicals. The technocracy perpetuated a bureaucratic maze that threatened to extinguish human autonomy and creativity.

The rhetoric of the Post-American pointed not only to evangelical appropriation of New Left social critiques, but also to a radical political style—one that sharply contrasted with the mid-century neo-evangelical inclination to court establishment structures. The church “forsakes the spirit of Christ,” an editor of Christianity Today had argued in 1967, when it uses “picketing, demonstration, and boycott.” Evangelical radicals countered that dissent was necessary to correct the status quo. Spiritual resources should be used to judge, not merely legitimate current conditions. The Post-Americans dismissed decorous evangelicalism as passé, even immoral, in the face of social injustice. Their protests, reflecting the demonstrative methods of the Left, such as guerrilla theater, picketing, leafleting, and direct confrontation, marked a profound departure from evangelical quietism.

The rhetoric of the Post-American pointed not only to evangelical appropriation of New Left social critiques, but also to a radical political style—one that sharply contrasted with the mid-century neo-evangelical inclination to court establishment structures. The church “forsakes the spirit of Christ,” an editor of Christianity Today had argued in 1967, when it uses “picketing, demonstration, and boycott.” Evangelical radicals countered that dissent was necessary to correct the status quo. Spiritual resources should be used to judge, not merely legitimate current conditions. The Post-Americans dismissed decorous evangelicalism as passé, even immoral, in the face of social injustice. Their protests, reflecting the demonstrative methods of the Left, such as guerrilla theater, picketing, leafleting, and direct confrontation, marked a profound departure from evangelical quietism.

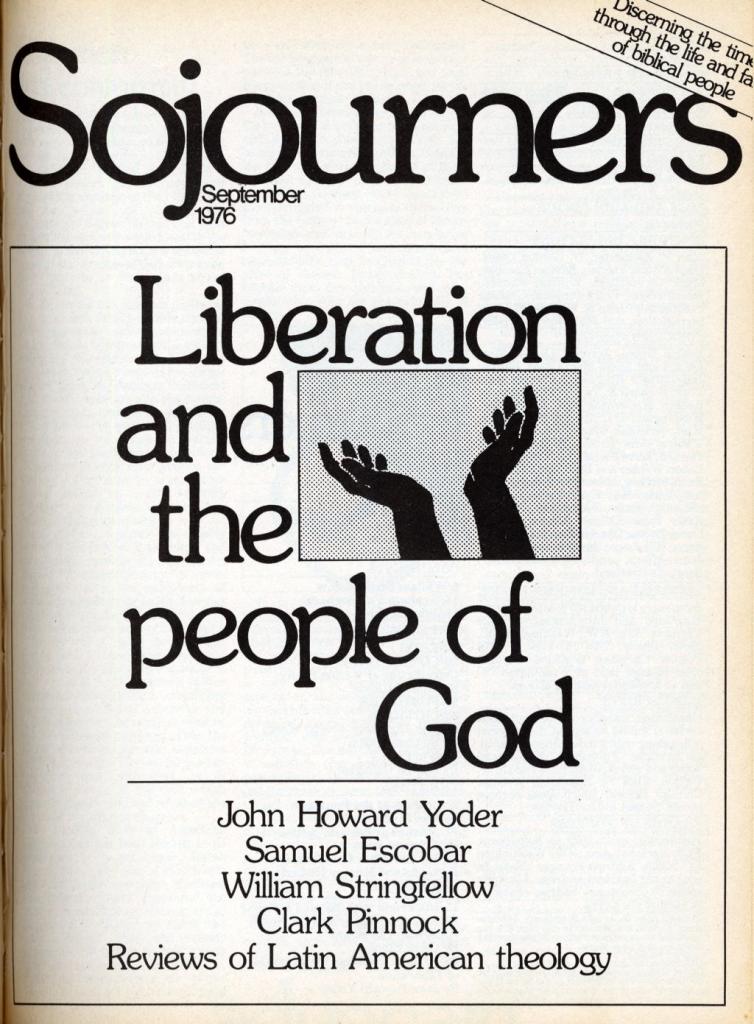

Renaming the magazine Sojourners—a biblical allusion that more clearly transcended the American context of the group’s founding name and captured a sense of community—and moving in 1975 into a dilapidated neighborhood in the northern section of the District of Columbia, the group and magazine continued their program of contentious dissent. They pledged to move more intentionally toward “nonviolent direct action.” “Our resistance to evil,” one statement read, “must never be passive but active, even to the point of sacrifice and suffering. … We therefore refuse military service, military-related jobs, war taxes, and will engage in nonviolent direct action and civil disobedience for the sake of peace and justice as conscience dictates and the Spirit leads us.”

Despite these sensibilities, which contrasted sharply with the religious right emerging in the 1970s and 1980s, the magazine’s subscription base grew. By 1983, it reached 55,000 subscribers. But it paid its employees only “subsistence level salaries,” and its reach couldn’t match the religious right, which was successfully attaching itself to the Republican Party. By 1990 the evangelical left as a coherent organizational movement had been left behind, exiled from American political structures and power, it had indeed been left behind.

Perhaps in response to its political homelessness, Sojourners evolved over the next decades. In the 1990s and 2000s, it became more centrist and establishment in ways that would have nauseated the twenty-somethings that launched it. Jim Wallis, softening from his fiery New Left suspicion of traditional political structures, began working comfortably with political moderates and the Democratic Party. A virulent critic of the technocratic Jimmy Carter in the 1970s, Wallis began to appear on event stages with the former president. By all accounts, the two had become good friends and found common political ground.

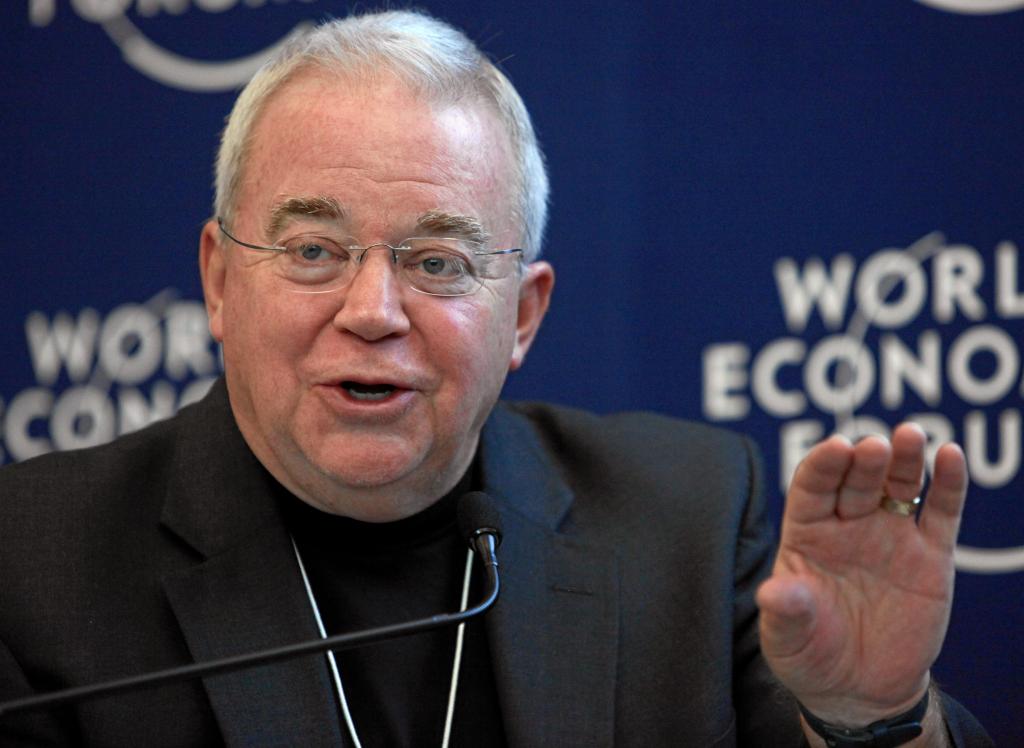

He worked with contemporary leaders too, some of the most powerful in the nation and world. On a single day, Wallis testified at a Senate hearing on the Employee Free Choice Act, participated in a conference call with President Obama’s Advisory Council on Faith-Based and Neighborhood Partnerships, and then enjoyed dinner with United Nations Secretary General Ban Ki-moon. Catapulted to prominence by his relationship with Obama—and by his 2005 bestselling book God’s Politics: Why the Right Gets It Wrong and the Left Doesn’t Get It—Wallis in the 2000s regularly appeared as a guest on CNN and on comic Jon Stewart’s The Daily Show. He attended World Economic Forum meetings in Davos, Switzerland, each year, and sales from God’s Politics, which spent fifteen weeks on the New York Times bestseller list, infused Sojourners with cash. In 2007 Sojourners sponsored a CNN forum on faith and religious values in which three of the top Democratic presidential candidates, Hillary Clinton, John Edwards, and Barack Obama, participated. According to Time editor Amy Sullivan, several years earlier the same forum had attracted only a single congressperson.

This new centrist trajectory offered progressive evangelicalism more political space and more potential to build an organized movement. For a time, it seemed to be working. “I’ve been 40 years in the wilderness, and now it’s time to come out,” he told a reporter as the magazine and a partner organization Call to Renewal surged. In 2006, longtime staffers, along with a new team of political organizers, fundraisers, and communications specialists, moved into gleaming new headquarters in Washington, D.C. Thirty-five years after the Post-American was founded, the magazine had arrived at the center of American politics.

Whatever one thinks about the political and ecclesiastical evolution of Sojourners, it has produced thousands of compelling articles. Some have been outrageous and provocative, others nurturing and deeply spiritual, still others smart and wise. The magazine has consistently encouraged its readers to think better, pray harder, and in the words of its mission statement, to live out “a gospel life that integrates spiritual renewal and social justice.” Sojourners has been a gift to American evangelicalism.