White evangelicals don’t like immigrants or refugees. Instead, they love Trump, travel bans, and border walls.

That’s the takeaway from Pew surveys about the intersection of religion and immigration over the past several years. If you scratch beneath the surface, evangelical opinion on such matters is more complex, not least because many evangelical leaders – Leith Anderson, Richard Stearns, Russell Moore – have articulated far more progressive stances.

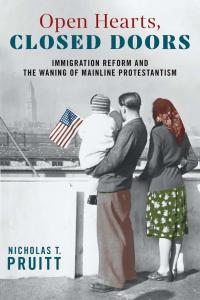

Nicholas Pruitt’s Open Hearts, Closed Doors scratches well beneath the surface of Protestant debates about immigration in the first two-thirds of the twentieth century. As Pruitt explains, “evangelicals have inherited many of the debates and talking points that mainline Protestants held at midcentury, while also echoing a similar missional impulse.”

Nicholas Pruitt’s Open Hearts, Closed Doors scratches well beneath the surface of Protestant debates about immigration in the first two-thirds of the twentieth century. As Pruitt explains, “evangelicals have inherited many of the debates and talking points that mainline Protestants held at midcentury, while also echoing a similar missional impulse.”

Pruitt begins his story with the run-up to the 1924 Immigration Act, which excluded all Asian immigrants and set strict limits and nation-based quotas for all other immigration outside the Western Hemisphere. White Protestant denominations at the time had robust “home mission” programs, which included a host of ministries to immigrants. Denominational leaders and many laypeople had absorbed the values of the Social Gospel movement, and in efforts to promote the “brotherhood of man” they ran schools on Ellis Island and counseled Mexicans facing deportation along the southern border.

In the 1920s, many white Americans – and thus many white Protestants – wanted much tighter restrictions on immigration, which they associated with political radicalism, Catholicism, and the loss of Anglo-Saxon and old-stock supremacy. Accordingly, Congress in 1924 passed an immigration act that expanded exclusion of Asian immigrants and imposed strict limits and a nation-based quota system on immigration from elsewhere outside the Western Hemisphere.

A host of Protestant voices opposed the 1924 act, both before and after its passage. In particular, they criticized the blanket exclusion of Japanese immigrants both because of its racism and because it hampered missionary efforts. “It has raised great question marks,” commented William Axling, a former Baptist missionary to Japan, “against such central Christian truths as a divine Fatherhood, world brotherhood, justice, fair play and good will.” At the same time, though, many Protestant leaders – and more laypeople, presumably – favored limitations on immigration and the quota system. “Protestants at the time the 1924 Immigration Act passed,” Pruitt concludes, “were not knee-jerk nativists hell-bent on keeping foreigners out of the country, but neither were they immune to nativst ideals.”

Three decades later, mainline Protestant leaders became vocal proponents of immigration reform. But what sort of reform? They largely opposed the 1952 McCarren-Walter Act, which ended the complete exclusion of Asian immigrants but maintained quotas based on national origins. President Harry Truman vetoed the 1952 act. “It repudiates our basic religious concepts,” Truman maintained, “our belief in the brotherhood of man, and in the words of St. Paul that ‘there is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither bond nor free … for ye are all one in Christ Jesus.” Congress overturned the veto, but the Truman’s rhetoric illustrates the cultural power of Protestant Christianity as of midcentury.

Indeed, mainline Protestantism was at the height of its public and political influence during these years. The National Council of Churches tirelessly lobbied Congress to pass more sweeping immigration reform. Methodist Bishop Gerald H. Kennedy spoke at the 1960 Democratic convention and called for an immigration law “commensurate with our national ideals and international long term interests.” Protestant leaders held conferences, issued statements, wrote letters, and met with politicians.

The Hart-Celler Act of 1965 did away with quotas based on national origins and exempted the relatives of U.S. citizens from immigration restrictions. According to Pruitt, who subtitled his book The Immigration Reform and the Waning of Mainline Protestantism, the 1965 act also did away with “mainline Protestant claims on America.” Progressive mainline leaders, some of whom had made peace with religious pluralism and some of whom maintained hope in a Protestant or at least Christian American future, “inadvertently … contributed to their culture decline.”

As Pruitt notes, there was a clear gap between the progressive reformist ideals of denominational leaders and those of the folks in the pews. In early 1965, 65% of all American Protestants wanted to maintain or decrease levels of immigration.

Open Hearts, Closed Doors is a compelling analysis of white mainline denominationalism during these decades. It should take its place along recent books by Healan Gaston, Matt Hedstrom, and David Hollinger, to name just a few. Pruitt excavates little-known stories about home missions, refugee resettlement, and immigration-reform lobbying, and his well-chosen quotes provide windows into the culture and mentality of his subjects.

I am less persuaded by the subtitle’s argument that immigration reform is closely connected to the “waning of mainline Protestantism.” Pruitt puts his finger on an irony, and on the mixed motives of mainline leaders. They “accepted cultural pluralism and immigration reform, while thinking they could still manage a Christian nation.”

They couldn’t, but not because Muslims, Hindus, Buddhists, or even Catholics flooded into the country. The waning of mainline Protestantism and its political influence is the story of internal collapse and demographic decline. It was evangelicals who muscled mainline Protestants out of the way, both numerically and in terms of political clout. Even today, Americans who adhere to non-Christian religions amount to less than ten percent of the population. Regardless, the mainline had lost much of its clout before the 1965 Immigration Act had much of an effect on the American religious landscape.

Finally, it’s worth noting, as does Pruitt, that opposition to immigration extends beyond the fuzzy confines of white evangelicalism. By a slimmer majority, white mainline Protestants also favored expanding the border wall during the Trump presidency. White mainline Protestants, again by a fairly slim margin, did not think the U.S. had a responsibility to accept refugees. The numbers for white Catholics are not all that different. Progressive Protestant (mainline and evangelical) support for refugees and immigrants has persisted, as have broad-based white Christian fears about racial and religious diversity.