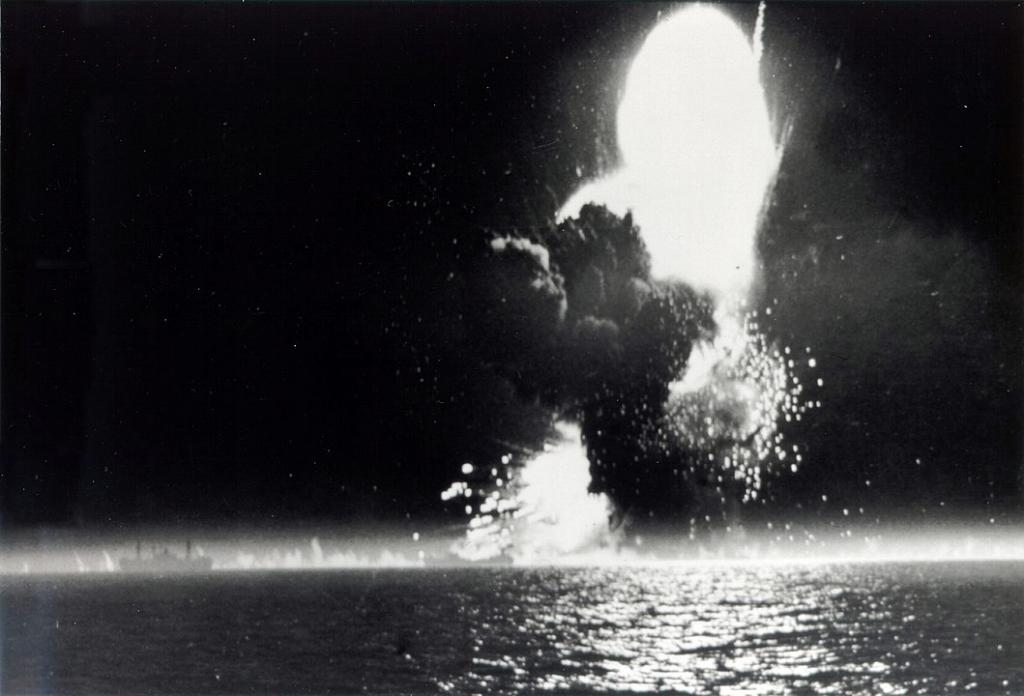

Like many Fourths of July before, I spent part of this weekend watching a movie about World War II. I’d first seen Greyhound last summer, thanks to our kids’ new MacBook earning us a free year of Apple+. Before we let that subscription lapse, I decided to rewatch this taut tale of a U.S. Navy destroyer escorting a convoy through a stormy, U-boat-infested Atlantic.

Starring and written by Tom Hanks, Greyhound is so economical that it tells its straightforward story in just over 80 minutes, which leaves little time for character development. (More on that before we’re done…) But Hanks does add a few intriguing brushstrokes to the portrait of his protagonist. A middle-aged officer finally commanding a ship at war for the first time, Commander Ernest Krause not only prays shortened versions of Martin Luther’s morning and evening prayers at the start and end of the film, but murmurs a table grace before every invariably interrupted meal.

And those few religious allusions are nothing compared to the source material for Greyhound: a 1955 novel by C. S. Forester entitled The Good Shepherd. While not as exciting as that author’s Horatio Hornblower tales or as immersive as Patrick O’Brian’s Aubrey-Maturin series, The Good Shepherd is the first naval history novel I’ve read that seems interested in what it means for a follower of the Prince of Peace to risk and cause death in a righteous cause, to live always amid the ending of life — having to decide which lives are worth more than others.

Forester’s Commander Krause (George, not Ernie, in command of the Keeling, not the Greyhound) not only prays to “the gentle Christ child” he first learned about from his long-dead mother, but is a Lutheran pastor’s son who knows the Bible so well that its “texts bobbed up in his mind as he tried to think. He could not ignore them.”

Virtually every experience conjures some memorized scripture from Krause’s memory. So the unseen U-boats are a “pestilence that walketh in darkness” (Ps 91:6) and watching a distant ship in the convoy reminds him to “Be sober, be vigilant, because your adversary the devil, as a roaring lion, walketh about, seeking whom he may devour” (1 Pet 5:8). Writing signals to other ships, he takes advice from both Ecclesiastes 5 (“Let thy words be few”) and Psalm 55 (“The words of his mouth were smoother than butter, but war was in his heart”). I stopped counting after a dozen such references, not even half the way into the book.

In the film version, little survives of this part of the characterization past a murmured proverb or two and the fact that Krause keeps an image of Christ in his cabin, framed by the reminder that Jesus remains the same, “yesterday, today, and forever.” And that image serves primarily to remind Hanks’ officer of the woman he wants to marry… who in the novel finds Krause’s prayers a source of amusement and leaves him for a lawyer.

For Forester’s Krause, seeing Hebrews 13:8 at the start of the novel “marked the fact that he was starting out on a fresh stage of his journey through the temporary world, to the grave and immortality beyond it.” But apart from giving “the necessary attention to that train of thought,” he is utterly consumed by the insistent demands of the “temporary world” — and seemingly uncertain that there is anything beyond it. “Weeping may endure for a night, but joy cometh in the morning,” he thinks as an exhausting night turns into a cold dawn. “It was not true. The heavens declare the glory of God. These heavens?… he thought of them with a bitter, sardonic revulsion of mind.”

Exhausted and frustrated, Krause comes close to casting “aside all thought of his duty, his duty to God.” He soldiers on — pausing just a moment to pray for forgiveness — but his duty is merciless, little touched by compassion. While Hanks’ version of Krause pauses pursuit of a U-boat in order to save four survivors of a torpedoed vessel, Forester’s does the opposite. “There was no Christian charity in the North Atlantic,” he tells himself. Like the Good Shepherd of John’s gospel, Krause is willing to lay down his life for others, but unlike the shepherd of Jesus’ parable, he protects the ninety-nine and leaves the one to perish.

I don’t think that Forester was a particularly devout Christian of any stripe, but his Lutheran protagonist in The Good Shepherd embodies something of Martin Luther’s notion that those who follow the Good Shepherd may nonetheless serve the kingdom of the world. Called to love his neighbor with what gifts he possesses, the Christian warrior is “under obligation to serve and further the sword by whatever means [he] can, with body, soul, honor or goods.” Just not in a particularly Christ-like manner, since “a man who would venture to govern an entire country or the world with the Gospel would be like a shepherd who should place in one fold wolves” — or Wolfpacks.

In his two-volume biography of his father, John Forester dispenses quickly with The Good Shepherd, dismissing Commander Krause as “a dull man who finds competence in the self-bounded, unlimited agony of war.” Meanwhile, even Greyhound’s generally favorable reviews have acclaimed it as a hypercompetent procedural, more interested in the machinery of naval combat than the people who operated it. “If that’s what you’re in the mood for,” concluded critic Alissa Wilkinson, “it’s thoroughly satisfying.”

It was, and it was. But as I watched Greyhound again last weekend, another reading suggested itself: if every character beyond Krause seems like a cipher, perhaps it’s because that’s how they seem to Krause.

It’s no surprise that a submerged enemy remains entirely invisible and silent in The Good Shepherd. (Though the movie lets an English-speaking U-boat officer periodically tap into the Greyhound’s communications and taunt Krause, a device only hinted at in the book.) But the men under Krause’s command are also a mystery to him. In Forester’s novel, he knows that he must “allow for the weaknesses of the human flesh under his command, and the flightiness of the human mind,” but he can only guess at the abilities, motivations, and fears of a crew he barely knows. Likewise, he agonizes over how the few, buttery words of his commands may be misinterpreted by the unseen British, Canadian, Polish, and other Allied ships in the convoy.

For that matter, the most important people in the entire story — the civilians whose survival gives the sailors their duty — are never seen, in novel or film. “A thousand miles ahead of them,” Forester starts his narration, waited “men and women and children, although they did not know of the existence of those particular ships, not their names, nor the names of the men inside them,” whose success would prevent hunger and disease, and tyranny.

That’s one reason I like to watch war movies on the 4th of July: they remind me that independence requires interdependence. But unlike families, congregations, and congregations, nations are imagined communities, few of whose members we will ever meet. So national service is almost always rendered to strangers, neighbors we love but never know.