When Dr. Seuss Enterprises announced that six books written by the late bestselling children’s author would be taken off the market because of their allegedly racist illustrations, the reactions predictably split along partisan lines. Some conservatives rushed to buy the books, pushing previously obscure titles like And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street or If I Ran the Zoo into Amazon’s top 20 list. On the other hand, some progressives questioned whether this move had really gone far enough in confronting racist undertones in Dr. Seuss’s work.

![Ted Geisel (Dr. Seuss) half-length portrait, seated at desk covered with his books] / World Telegram & Sun photo by Al Ravenna. - Library Of Congress Public Domain Image](https://cdn4.picryl.com/photo/2019/09/09/ted-geisel-dr-seuss-half-length-portrait-seated-at-desk-covered-with-his-books-95b9cd-1600.jpg)

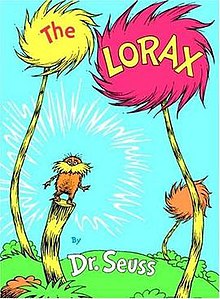

The irony of all of this is that Theodor Seuss Geisel (1904-1991) was never a conservative during his life. He was a politically outspoken, rights-conscious, northeastern liberal – born in Springfield, Massachusetts, and educated at Dartmouth – whose books were guided by the progressive or liberal politics of his age. From the moment he began drawing political cartoons urging the United States to stand up against Nazism in early 1941 to the moment he wrote The Butter Battle Book (1984) as an allegory against the nuclear arms race during the Reagan administration, Dr. Seuss supported the internationalist, human rights-oriented wing of the Democratic Party. He wrote numerous stories about the virtues of anti-elitist democracy, as any reader of Yertle the Turtle (1958) or the story of King Looie Katz can attest. He exposed the foolishness of racial discrimination based on skin color in The Sneetches (1961). And he wrote a bestselling environmentalist tract called The Lorax (1971).

In every decade of his career, Dr. Seuss trumpeted the prevailing American liberal opinion of the time. In the year leading up to America’s involvement in World War II, he denounced Adolf Hitler and sided with FDR in favor of American intervention in Europe. In the Cold War years of the 1950s, he advocated for democracy in his lampoons of totalitarian turtles who were toppled by a small “Yawp.” At the height of a liberal ecumenical civil religion of good will and acceptance in the late 1950s, he wrote his bestselling heartwarming book about the meaning of Christmas being found in joy and human (or Who-Grinch) kindness. In the year of the Freedom Rides, he wrote against racism. Immediately after the first Earth Day, he embraced the cause of environmentalism. When liberals denounced nuclear arms buildup, Dr. Seuss did, too, despite his earlier advocacy of international military intervention. When liberals called for President Richard Nixon’s resignation, Dr. Seuss did, too, publishing “Richard M. Nixon, Will You Please Go Now?” in the Washington Post. (Fans of the good doctor will probably recognize the allusion to Marvin K. Mooney in the line, “Richard M. Nixon, will you please go now! The time has come. The time is now”).

In short, Dr. Seuss had impeccable liberal credentials; at no point in his career was he ever out of step with the liberal mainstream, and at every point he favored the expansion of democracy and concern for the less fortunate. The heroes of his books were often the oppressed and marginalized. Of course, Dr. Seuss didn’t use words like “marginalized” in his children’s books, but what better way to characterize the small unseen community that Horton the elephant valiantly tried to protect in Horton Hears a Who (1954) – the book whose most memorable line might be “A person’s a person no matter how small”?

The progressive critics of Dr. Seuss are therefore targeting a fellow liberal when they excoriate Dr. Seuss’s racism. Yet this does not mean they are entirely wrong. Some of Dr. Seuss’s early works from the 1930s and 1940s do contain racist imagery, and his World War II political cartoons of Japanese people (whom he derisively called “Japs” at the time) did feature exaggerated, stereotyped facial features for the purpose of derision and ostracism. But this probably tells us as much about the history of American liberalism as it does about Dr. Seuss. And I fear that both the progressive critics and the conservative defenders of Dr. Seuss may misunderstand this larger history.

Perhaps the key to understanding the racial attitudes of mid-twentieth-century American liberalism – including the liberalism of Dr. Seuss – is to realize that both the civil rights advocacy and the racial insensitivity of white American liberals were based on a humanitarianism that could be both refreshingly egalitarian and shockingly racially insensitive at the same time. In fact, it was precisely because they wanted to reform the world along egalitarian, democratic lines that mid-twentieth-century progressives could, in the name of progressivism and democracy, pursue policies that today we realize are the very opposite of such ideals.

This was certainly true of Dr. Seuss’s fellow New Englanders, who, as Melissa Wilde’s recent book Birth Control Battles shows, were the nation’s strongest advocates of eugenics during the 1920s. And the loudest calls in New England for lowering the birth rates of the region’s Catholic and Jewish immigrants came from the region’s most theologically and politically progressive denominations that enthusiastically championed the Social Gospel. The Unitarian, Universalist, and Congregationalist churches were in the vanguard of eugenics advocacy in the 1920s because they believed that the key to reducing poverty and promoting democracy and progressive thinking was to reduce the birth rate among impoverished immigrants whom they believed would be a drain on society. In other words, they could be both Social Gospel advocates and eugenicists at the same time.

Whether or not the Episcopal church that the young Ted Geisel attended with his mother during the 1910s and 1920s followed the lead of its own denomination and other liberal New England churches in openly championing eugenics, the young Geisel undoubtedly was exposed at some level to the prevailing New England message that social reform necessitated limitations on the prerogatives of the less fit. At the time that he entered Dartmouth, the small New Hampshire college maintained an admissions quota that sharply limited the number of Jewish students in order to preserve the white Anglo-Saxon Protestant heritage of the school. “Life is so much pleasanter in Hanover, the physical appearance of the place is so greatly benefited and friends of the college visiting us are so much happier with the decreased quota of the Hebraic element,” Dartmouth College’s president mused in 1933. Dr. Seuss resisted the anti-Semitism of his college’s president, and he embraced an internationalist outlook that sought to welcome people from other cultures instead of excluding them, but that did not mean that he was entirely immune from the racially charged thinking that pervaded American society at the time.

When Dr. Seuss graduated college and embarked on a brief career in advertising and political cartooning, he entered a political world in which liberal defenses of human rights were inseparably intertwined with racist actions. Liberals of the early 1940s sanctioned some of the most egregious human rights violations against Japanese Americans in the name of winning a war on behalf of human rights. The American president who signed the executive order authorizing the internment of Japanese Americans in California was the liberal internationalist Franklin D. Roosevelt, and the California governor who oversaw the relocation was the liberal Earl Warren, who, as chief justice of the Supreme Court in the next decade, would author the Brown v. Board of Education decision mandating the desegregation of American public schools. Roosevelt, in fact, ordered the internment while loudly trumpeting the principles of civil rights and civil liberties. Only two years earlier, he had told the American Committee for Protection of Foreign Born that “we must scrupulously guard the civil rights and civil liberties of all our citizens, whatever their background,” because “any oppression, any injustice, any hatred, is a wedge designed to attack our civilization.” But in Roosevelt’s view, the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor was an attack on civilization, and civil liberties violations that might be unthinkable in peacetime were necessary to win a war that was necessary to protect the rights and liberties not only for Americans but for the world.

This was Dr. Seuss’s attitude as well. At the same time that he was drawing anti-Japanese cartoons, he also published cartoons that promoted international human rights and humanitarian intervention to save Europeans from Hitler. His cartoons blasted the America First Committee for their lack of concern about children in Europe who were “foreign”; the loss of freedom in Europe should be Americans’ concern as well, he argued. And if the Japanese were fighting against human rights, he had no qualms about using the racist imagery of the day to denounce the Japanese through his art.

In doing so, of course, Dr. Seuss drew on negative white stereotypes about Asians as “other.” And this was reflected in his other work during that time as well. One of the complaints about And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street is that it includes a picture of a man with slanted eyes eating with chopsticks in a pose that could be considered demeaning and racist. In 1937, when Dr. Seuss wrote this book, US immigration policy prohibited all immigration from Asia, and people of Asian descent comprised less than 1 percent of the American population. Most of those people lived in California or the territory of Hawaii, which meant that a small-town New Englander like Dr. Seuss would have been highly unlikely to have had meaningful interactions with any of them. Did Dr. Seuss therefore think of Asians as “other”? Probably. So did a lot of other liberal Americans of his day.

But if the young Ted Geisel viewed Asians as “other,” he did so not out of malice or even necessarily smug superiority but out of a naïve boyhood dream to break out of Springfield and see a world that he could encounter only in his imagination. And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street is the product of a boyhood daydream that imagines a town transformed by something more interesting than a bunch of white New Englanders who had never left the region. Dr. Seuss imagined men from India riding elephants and Chinese eating with chopsticks. At the time Dr. Seuss wrote this book, the first Thai restaurant in the United States was still more than twenty years in the future. Because of American immigration policy – which was in turn based on anti-Asian racism – a young Ted Geisel (and even a young adult Dr. Seuss) could only dream about seeing Asians in a small New England town. What he imagined might have reflected white stereotypes of Asians more than reality. But if that is the case, it’s hard to see how it could have been otherwise in a nation that refused to let Asians come in.

The best response to Dr. Seuss, I think, is neither to uncritically defend the pictures in his early books (as some conservatives are doing) nor to condemn them (as some progressives have), but rather to seek to understand their historical context and their place in Dr. Seuss’s larger work. Dr. Seuss’s creative talent was extraordinary, and the words and pictures of his book were sui generis, but when it came to politics, he was a fairly conventional follower of the liberalism of his day. Sometimes those liberal views led him to adopt imagery that we now consider racist, though more often they led him to embrace ideas of equality and democracy that moved away from the anti-Semitism of Dartmouth College and toward the human rights vision of Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt. It’s sadly ironic, I think, that a man who spent his entire adult life following the path of political progressivism is now being shoved aside by a few political progressives who are heirs to that same ideology. It is far better, I think, to realize that whatever shortcomings there might have been in Dr. Seuss’s political vision were shortcomings of twentieth-century American political liberalism. These shortcomings cannot be addressed merely by taking some of Dr. Seuss’s books out of circulation, but instead must be confronted with an honest reckoning of a much larger part of our past.

A Christian who believes in the doctrine of original sin has the tools to look at a person like Dr. Seuss both critically and sympathetically. Dr. Seuss was the product of a twentieth-century secularized liberal Protestantism. Though he attended Lutheran and Episcopal churches as a child and even memorized the books of the Bible in his youth by using a creative rhyme that he made up (“The great Jehovah speaks to us / In Genesis and Exodus; / Leviticus and Numbers, three / Followed by Deuteronomy”), he was never, as far as I know, a Christian believer in any orthodox or evangelical sense of the term, and as an adult, he took his moral compass more from a political ideology than from religion. But in its secularized political form, liberal Protestant ideals of equality and universality remained his guides throughout his life, and they led him to some inspiring insights of concern for the less fortunate, and perhaps even to a joie de vivre that he desperately tried to hold onto during moments of personal grief, such as when his wife committed suicide after more than a decade of illness, leaving the children’s book author without any children of his own.

In the midst of the positive aspects of the secularized liberalism he inherited, Dr. Seuss imbibed both the insights and the blind spots of his time and place – including insights and blind spots that shaped his thinking on race. On race, he wrote as a 1940s liberal during the 1940s, and as a 1960s liberal during the 1960s. He was, in other words, a liberal man of his time, and his writing reflected all that was both right and wrong with twentieth-century American liberalism. And for such a man I think we can have both admiration and compassion, not least because he was a faithful follower of the liberal ideology of his own age, even going so far as to change with it through its every evolution. Had he been a New England liberal in the nineteenth century, perhaps he would have been a stronger moralist but less of an egalitarian. And had he been a New England liberal in the twenty-first century – who knows? Maybe he would now be voting to take his own early books out of circulation. But he lived in the mid-twentieth century, and as a product of that time, his works embody all of the positive and negative qualities of that era’s ideology.

Regardless of what choices Dr. Seuss may or may not have made if he had lived in a different time and place, I think that for myself personally, Dr. Seuss’s political journey gives me the desire to transcend the values of my own time and place, even as it also gives me the realization that fully achieving this will be impossible on this side of heaven. I personally would like to have a more fixed political compass than a prevailing political ideology as my guide, because I suspect that, just as Dr. Seuss discovered, the moral norms of political progressives in one decade will not necessarily be the moral norms that guide them in the next. If we want to avoid the vicissitudes that Dr. Seuss experienced over the course of his half-century creating children’s books, maybe we’ll need to have a firmer ideological anchor. But regardless of how hard we try, we know that we’re never going to fully escape the fallacies of the cultural moment in which God has placed it. We’re a part of this world even as we seek to be transformed in our thinking. And if that’s the case even for the most earnest believer, perhaps it’s not surprising that it would also be true for an unbeliever – even an extremely gifted liberal and egalitarian unbeliever like Dr. Seuss.