Last week I received an email from my alma mater. Philip Ryken, the president of Wheaton College, wrote:

Dear David,

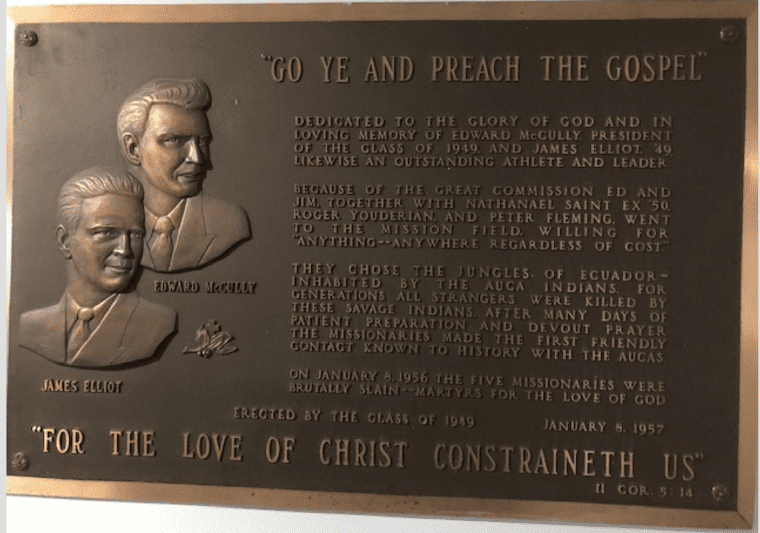

I write regarding the plaque hanging in the lobby of Edman Chapel that honors Jim Elliot ’49, and Ed McCully ’49, who—along with Nate Saint Ex ’50, Roger Youderian, and Pete Fleming—were slain in 1956 while endeavoring to carry out the Great Commission with indigenous peoples of Ecuador. In a heartfelt act of remembrance, the Wheaton College Class of 1949 gave this plaque to the College in 1957 to honor their fallen classmates and their colleagues.

In the 64 years since the College received this gift, we have continued to grow in our understanding of how to show God’s love and respect to others. Recently, students, faculty, and staff have expressed concern about language on the plaque that is now recognized as offensive. Specifically, the word “savage” is regarded as pejorative and has been used historically to dehumanize and mistreat indigenous peoples around the world.

Any descriptions on our campus of people or people groups should reflect the full dignity of human beings made in the image of God. With this in mind, the Senior Administrative Cabinet will appoint a task force to review the wording of the plaque and to make a specific recommendation by May 1 for its careful rewording and replacement, subject to a final decision by the Senior Administrative Cabinet, in consultation with the Board of Trustees. Members of the task force will include a faculty historian, a faculty missiologist, a representative from the Wheaton College Alumni Association Board of Directors, a graduate student, and an undergraduate student. . . .

The language on the plaque implicates more than just young Wheaton alumni. It reflects a troubling discourse embedded in the midcentury white evangelical missionary enterprise. Consider, for example, Through Gates of Splendor (1957), the widely read chronicle of the slayings written by Jim Elliot’s widow Elisabeth Elliot. She recalled that their first encounters with “isolated, unconquered, seminomadic remnant of age-old jungle Indians . . . thrilled their young blood. Would they someday be permitted to have part in winning the Aucas [a pejorative term meaning “savage” in the lowland Quichua language] for Christ?” As they engaged these warriors face to face, however, the young missionaries worried about living close to fundamentally untrustworthy “stone age” peoples. There was hope that the Huaorani could be redeemed, but the spiritual and cultural distance between civilized white Americans and the inscrutable Indians seemed enormous. In a raw concluding chapter, Elliot described dragging mutilated corpses to a common grave during a violent tropical storm—all while worrying that these “natural born killers” were waiting in the jungle to strike again. The Life magazine correspondent who accompanied the search party noted the eerie, grim, fantastical scene as helicopters descended into a cove and as guards with fingers on triggers stared tensely into the jungle. Everything about Elliot’s narrative suggested the savagery and otherness of the Huaorani.

The language on the plaque implicates more than just young Wheaton alumni. It reflects a troubling discourse embedded in the midcentury white evangelical missionary enterprise. Consider, for example, Through Gates of Splendor (1957), the widely read chronicle of the slayings written by Jim Elliot’s widow Elisabeth Elliot. She recalled that their first encounters with “isolated, unconquered, seminomadic remnant of age-old jungle Indians . . . thrilled their young blood. Would they someday be permitted to have part in winning the Aucas [a pejorative term meaning “savage” in the lowland Quichua language] for Christ?” As they engaged these warriors face to face, however, the young missionaries worried about living close to fundamentally untrustworthy “stone age” peoples. There was hope that the Huaorani could be redeemed, but the spiritual and cultural distance between civilized white Americans and the inscrutable Indians seemed enormous. In a raw concluding chapter, Elliot described dragging mutilated corpses to a common grave during a violent tropical storm—all while worrying that these “natural born killers” were waiting in the jungle to strike again. The Life magazine correspondent who accompanied the search party noted the eerie, grim, fantastical scene as helicopters descended into a cove and as guards with fingers on triggers stared tensely into the jungle. Everything about Elliot’s narrative suggested the savagery and otherness of the Huaorani.

Intriguingly, Elliot’s personal views shifted as she remained in the jungle to live with her husband’s killers, learn their language, and perform medical work. Her sequel, The Savage My Kinsman (1961), played with the established categories she had taken for granted in Through Gates of Splendor. While the book continues to show the brutality of the killings in striking rawness—one photograph shows a spear sticking in the side of a corpse floating in the river, and Elliot described her repulsion at the Huaorani’s “crudeness, limited interests, incomprehensible language, their everlasting meddling with my possessions and my affairs”—she found much that was attractive. “I watched the people I had called savages. Somehow immortal in their nakedness, speaking together in the subdued tones used among Indians, laughing childishly over small things, interested in the tiniest events about them, they seemed a lovely contrast to the elaborate dress, the loud voices, the sophisticated humor, the world-consciousness of our civilization.” Portraying them in an almost Edenic light, dozens of pictures of naked Huaorani, many of them frolicking alongside Elliot’s four-year-old daughter, hinted at native innocence. To use nineteenth-century terminology, they had become “noble savages.”

Intriguingly, Elliot’s personal views shifted as she remained in the jungle to live with her husband’s killers, learn their language, and perform medical work. Her sequel, The Savage My Kinsman (1961), played with the established categories she had taken for granted in Through Gates of Splendor. While the book continues to show the brutality of the killings in striking rawness—one photograph shows a spear sticking in the side of a corpse floating in the river, and Elliot described her repulsion at the Huaorani’s “crudeness, limited interests, incomprehensible language, their everlasting meddling with my possessions and my affairs”—she found much that was attractive. “I watched the people I had called savages. Somehow immortal in their nakedness, speaking together in the subdued tones used among Indians, laughing childishly over small things, interested in the tiniest events about them, they seemed a lovely contrast to the elaborate dress, the loud voices, the sophisticated humor, the world-consciousness of our civilization.” Portraying them in an almost Edenic light, dozens of pictures of naked Huaorani, many of them frolicking alongside Elliot’s four-year-old daughter, hinted at native innocence. To use nineteenth-century terminology, they had become “noble savages.”

Elliot sought to humanize the Huaorani for her evangelical readers. Living with the tribe, she explained, had made their strange customs intelligible. In a chapter entitled “The Civil Savages,” Elliot described intricate gender and marriage customs, and she sought to rehabilitate the image of the Huaorani by contrasting their habits with American sins. The Huaorani, she notes, did not participate in malicious gossip, vanity, or covetousness. The typical Huaorani man knew nothing of “drunkenness or wife beating. He may kill his neighbor, but he does not fight with him. . . . He may practice polygamy, but he faithfully supports all of the wives he has. . . . He does not wear clothing, but he has a strict code of modesty and is totally free from the American preoccupation with the human body, and all the absurd inhibitions this involves.” Elliot concluded, “At first glance, one might ask of the Auca way of life, ‘Is this the best they can do?’ but one soon finds that ‘this’ is very well indeed.”

Elliot’s third book, a novel called No Graven Image (1966), went much, much further. Its protagonist, a young missionary named Margaret Sparhawk, sailed to South America on a ship with air conditioning, perfumes, cigarette smoke, steaks, and alcohol. “The irresponsibility was intoxicating,” confided Margaret to the reader. “I found it hard to acknowledge that spiritual need was not somehow correlative to physical.” She disembarked from this spectacle of Western luxury to encounter the horrors of life in a poverty-stricken third-world city. There was a man with no eyes and no feet sitting on the pavement “with his back against a building … his head lolling back on his neck.” A girl of about eight “lay in his lap, emaciated and limp, with immense black eyes rimmed with shadows and shining with fever.” Margaret realizes that “witnessing” to him is not enough, despite the evangelical mandate to “tell them of Christ.” Like Bob Pierce of World Vision and swelling ranks of American evangelicals contemplating foreign misery, Elliot meant to encourage holistic missionary work.

Elliot’s third book, a novel called No Graven Image (1966), went much, much further. Its protagonist, a young missionary named Margaret Sparhawk, sailed to South America on a ship with air conditioning, perfumes, cigarette smoke, steaks, and alcohol. “The irresponsibility was intoxicating,” confided Margaret to the reader. “I found it hard to acknowledge that spiritual need was not somehow correlative to physical.” She disembarked from this spectacle of Western luxury to encounter the horrors of life in a poverty-stricken third-world city. There was a man with no eyes and no feet sitting on the pavement “with his back against a building … his head lolling back on his neck.” A girl of about eight “lay in his lap, emaciated and limp, with immense black eyes rimmed with shadows and shining with fever.” Margaret realizes that “witnessing” to him is not enough, despite the evangelical mandate to “tell them of Christ.” Like Bob Pierce of World Vision and swelling ranks of American evangelicals contemplating foreign misery, Elliot meant to encourage holistic missionary work.

The novel was also a stern indictment. Elliot’s oeuvre to this point had gently scolded American insularity, but No Graven Image issued a firm rebuke through its descriptions of ugly missionizing. Veteran missionaries who greet Margaret upon her arrival advise her to wash her hands a lot when interacting with the Indians. She also encounters a well-meaning, but culturally insensitive American missionary executive. As Margaret takes “Mr. Harvey” on her daily rounds of visiting the Quechua Indians, he takes photographs intrusively, turns up his nose at food, and distributes religious tracts to the illiterate Quechua. Her sending churches view the Indians as “godless heathens, pagan savages, degenerate serfs—they were all the same, and Christ had died for them.” Elliot, who later became famous for her establishment defense of male headship in marriage, was depicting a horror show of evangelical ethnocentrism. It was a portrait that primed evangelical children to question the superiority of American culture and politics.

The novel also pointed the way toward redemption. At first repulsed by the smells of the primitive thatch homes, Margaret grows to admire the Indians’ commitment to sustainable practices. For hundreds of generations, she notes, they “had cohabited with fleas and were not prepared to panic over them and spend hard-earned sucres on DDT just because the white man did.” Margaret also discovers their rich heritage. She delights in the elaborate costumes of a festival celebrating Saint Rafael. Though the music initially seems badly composed and performed, she realizes that it was using a sophisticated pentatonic scale. Not every culture, she observes, uses the Western octave. “The white man,” Margaret decides, “was not master of all that was good.”

At the heartbreaking end of the novel, Margaret plays a role in the death of Pedro, a new convert who died from a reaction to penicillin, which she had prescribed. She confesses, “I saw for the first time my own identity in its true perspective. Once I had envisioned Pedro, highland Indian, Christian, translator of the Bible, soldier of the Cross—because I, Margaret Sparhawk, had come. He was my project, he was the star in my crown. But here was another cross, with a name and a date, to mark where a dead man lay—because I, Margaret Sparhawk, had come.” Margaret’s confession was Elliot’s confession. Written for impressionable young missionary prospects, she warned that evangelization could be destructive.

The fictional character of Margaret meets considerable pushback. Some distressed supporters do not like how she questions traditional missionary approaches. One is suspicious of her “sympathy for the Indian outlook.” Donors contribute less money.

Author Elisabeth Elliot suffered similar rebukes in real life. While the New York Times praised the book—pronouncing it a “subtle and savage” satire on “fundamentalist missionary customs and attitudes”—evangelical insider Harold Lindsell displayed considerable ambivalence. The Christianity Today editor wrote that he appreciated its literary qualities, but he was not impressed with Elliot’s penchant for offering “no answers at all.” In fact, according to historian Sarah Ruble, he expressed “haunting doubt” about her evangelical credentials. Her critique struck too close to conservative certainties about the missionary enterprise.

The limits of Elliot’s critique became clear at the 1966 World Congress of Evangelism in Berlin. Held just three months after Lindsell’s uneasy review of Elliot’s No Graven Image, the gathering featured a traditionalist missiology. In front of hundreds of newsmen, including a reporter from the New York Times, two Huaorani converts just out of the jungles of Ecuador stood on a concrete Berlin stage as a display of successful religious conversion. The scene would have been funny—they stomped on the concrete surfaces, said an observer, “amazed that earth’s crust could get so hard”—if it wasn’t so poignant for attendees. Komi Gikita and Kimo Yaeti, the murderers of the five American missionaries, had been redeemed. As cameras flashed, the dazed Huaorani (who may have thought they were being worshipped) gave their “testimony” through Rachel Saint, whose brother was killed by Komi’s father. The twenty-nine-year-old Kimo, known back home as Red Squirrel, told reporters, “Before knowing about Itota (Jesus), we killed. There was much revenge and much madness.” But after the killings “we heard that the word of God is stronger than the devil. We listened. We were told that God said not to spear other people, only the wild hogs, the tapir, and the fish of the stream.” He concluded, “Before I lived sinning and God has done wonderful things and now I live well.” Of the ninety remaining members of the tribe, only five had not yet “received Christ as their personal Savior.” In fact, Kimo, only the year before, had helped baptize Saint’s two children near the spot on a river where the massacre occurred. Now dressed in suits and ties with hair parted on the side, as if now truly civilized, they stood as trophies of evangelical missions for the 1,200 delegates from nearly 100 nations gathered in Berlin.

Elliot must have liked the themes of redemption and nonviolence embodied on that stage. At the same time, the scene perpetuated the tropes of savagery and civilization she had worked so hard to leave behind. The evangelical establishment had rejected her critique and doubled down on a dualistic missions discourse. At Wheaton it remained carved in bronze for the next sixty-four years.

Elliot must have liked the themes of redemption and nonviolence embodied on that stage. At the same time, the scene perpetuated the tropes of savagery and civilization she had worked so hard to leave behind. The evangelical establishment had rejected her critique and doubled down on a dualistic missions discourse. At Wheaton it remained carved in bronze for the next sixty-four years.