Is the theologically conservative Reformed wing of evangelicalism going to permanently divide over race and politics?

This month, Kevin DeYoung, a pastor and professor at Reformed Theological Seminary (as well as a popular author and a major figure in the “young, restless, and Reformed” movement) wrote an insightful article for the Gospel Coalition tracing a movement fissure that is in the making. On one side of the divide are Reformed racial progressives who support Black Lives Matter and denounce Donald Trump and Christian nationalism. On the opposite side are Reformed political conservatives who voted for Trump and who believe that Black Lives Matter is anti-Christian. And in the middle are two groups of moderates – one group that leans toward the progressives and probably did not vote for Trump but wants to keep the peace with the conservatives, and the other that leans toward the conservatives but does not want to disfellowship the progressives even while questioning some of their decisions.

DeYoung places himself in this last camp of conservative-moderates. He would like to reunite the coalition, but fears that it already may be too late to bring the progressives and conservatives together again – a situation that he finds lamentable, especially in view of the common theological ground that the two camps share on so many other issues. After all, as DeYoung noted, all groups in this coalition of conservative Presbyterians, Reformed Baptists, and the like are biblical inerrantists and strong Calvinists, and most are complementarians or at least lean in that general direction. With so much to unite them theologically and even culturally, are issues of race and politics really sufficient to permanently break apart this coalition?

No one can reliably predict the future, of course, but for insight into this question, I’d like to consider the historical experience of another evangelical movement that experienced a permanent schism over race and politics in spite of its message of unity and the moderation of its most prominent leader. That movement is 19th-century Stone-Campbell Restorationism.

At first glance, the Stone-Campbell Restorationist movement, which eventually gave rise to the Churches of Christ and the Disciples of Christ (as well as the Independent Christian Churches), might seem an unusual choice for an analogy with contemporary conservative Reformed evangelicalism. As a product of the heavily Arminian Second Great Awakening, the Stone-Campbell Restorationist movement was one of the most strongly anti-Calvinist Protestant movements in American history; the free will of the unregenerate sinner to choose or reject Christ was a key tenet for the movement. But aside from this point of theology, which obviously is at odds with the views of the “young, restless, and Reformed” movement of the early 21st century, 19th-century Stone-Campbell Restorationism and early 21st-century conservative Reformed evangelicalism share a great deal in common: Both movements were strongly biblicist, both favored rational and logical appeals over emotional displays, and both promised a textual and theological pathway to the restoration of the original Christian message. Presaging the trans-denominational appeal of 21st-century Reformed evangelicalism, the 19th-century Stone-Campbell Restorationist movement drew converts from Baptist, Presbyterian, and Methodist groups in roughly equal measure. But perhaps most significantly, Stone-Campbell Restorationism paralleled the “young, restless, and Reformed” movement in its view of the church’s relationship to politics; although interested in social and political reform causes, many members of the movement believed that the restoration of the New Testament church offered a pathway to social reform that was superior to what any political party could advocate. The only problem was that the members of the movement could not agree on what that pathway should be. Nowhere was this more evident than on the issue of slavery.

Most members of the Stone-Campbell movement, which was concentrated most heavily in the Appalachian and trans-Appalachian regions of Ohio and Tennessee, were generally opposed to slavery. Some of the northern Ohio Campbellites were abolitionists, and a smaller number of southerners (especially those in Alabama or Texas) owned slaves, but the majority believed in abstaining from direct participation in slave ownership – yet they disagreed about how to do it.

David Lipscomb

David Lipscomb

One of the leading voices among the conservatives was David Lipscomb of Tennessee. When Lipscomb was a boy, his father traveled to Illinois to free the family’s slaves, but upon reaching adulthood, Lipscomb himself seems not to have fully shared his father’s views, since he owned five slaves at the time of the 1860 census. But Lipscomb was not a Confederate. In the presidential election of 1860, he voted for the Constitutional Union Party candidate John Bell, not a secessionist or states’ rights Democratic candidate. During the Civil War, he refused to fight, and by the end of the war, he had become so disillusioned with politics that he decided to renounce voting in the name of Christ. Only through the pursuit of the kingdom of God could a Christian reform society; politics would only corrupt the church and corrupt the Christian.

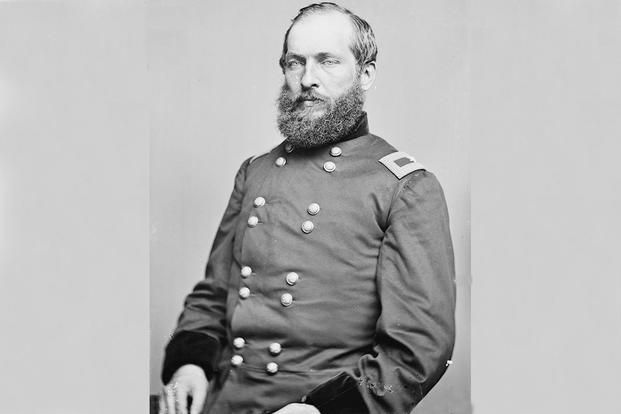

The most politically prominent figure among the progressives was James A. Garfield, an Ohio Disciples preacher-turned-politician who served as a Union general and was later elected president of the United States after serving in the US House of Representatives. Garfield became increasingly agitated about slavery during the late 1850s and, immediately after the Civil War, he embraced the cause of Black voting rights and the Radical Republican vision of Reconstruction. His strong antislavery views led him to embrace a path to social reform that Lipscomb considered dangerously heretical. For Lipscomb, slavery seems to have been a matter of indifference, but violence and politics were not. For Garfield, freeing the slaves and protecting African American civil rights were important enough causes to fight for – even if it meant rethinking the principles of biblical interpretation that had guided the “founding father” of the movement.

Alexander Campbell, the most influential figure in the movement – and the one who, along with Barton Stone, probably came closest than anyone else to being this highly decentralized movement’s founder – was both a pacifist and a moderate opponent of slavery, though for him, that did not necessarily mean embracing the antislavery cause in the political sphere. He had such strong faith in the church’s capacity to solve all social problems that he saw no need to embrace a political solution to the matter. He also believed that while the evidence seemed to suggest that 19th-century American slavery was incompatible with the teachings of Jesus, it was not so clear-cut as to justify condemning or excommunicating a fellow Christian who thought differently and owned slaves. Campbell’s moderation was analogous perhaps to Kevin DeYoung’s in the 21st century; he shared some convictions with people on both sides of the divide, but also wanted, above all, to preserve the unity of the movement.

That unity was not preserved. In 1863, members of the Stone-Campbell movement’s American Christian Missionary Society, meeting in Cincinnati (and largely without southern delegates, who were unable to travel to Ohio during the Civil War), voted to endorse the Union government and “tender our sympathies to our brave and noble soldiers in the field, who are defending us from the attempts of armed traitors to overthrow our Government.” Lipscomb and other southerners in the Stone-Campbell were aghast. Not only had the northern delegates acted precipitously against their southern brothers and sisters but they had also sullied the church by linking it to a political cause, and a violent one at that. They never forgave the northern Christians for this abrogation of the movement’s principles, as they saw it.

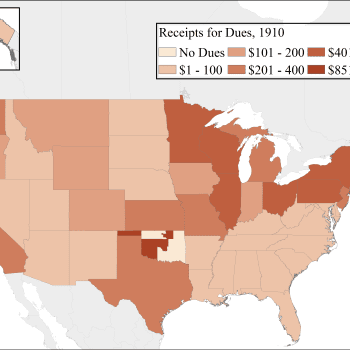

With Campbell’s death in 1866, the movement lost a moderating figure who could keep the two sides from growing further apart – if even Campbell could have done so, which is perhaps doubtful. Over the next few years, the faction of the movement identified with Lipscomb and other southerners denounced the more progressive Disciples for other innovations, such as instrumental music in worship and even the idea of missionary societies themselves. Both sides in the controversy saw their disagreements as doctrinal in nature, but in the mid-1960s, historian David Edwin Harrell conducted an exhaustive socioeconomic study that found that these doctrinal disagreements fell along economic lines; the conservative Churches of Christ associated with Lipscomb were much poorer, more rural, and more likely to be confined to the South than the more progressive Disciples congregations associated with the Republican Party politics of James Garfield and the American Christian Missionary Society. By 1906, the two factions were listed in the religious census as separate denominations – a recognition of a reality that probably began as early as the 1860s.

What implications does the historical trajectory of the 19th-century Stone-Campbell Restorationist movement – which is not usually told in the context of the history of Reformed evangelicalism – have for the future of the “young, restless, and Reformed” Christians? I think that it suggests that religious unity in the face of political divisions over racial justice is almost impossible to maintain, even for a movement that prioritizes it.

By some measures, one would have expected the Stone-Campbell movement not to divide in the Civil War. A moderate antislavery ethos pervaded the movement, even in parts of the South. There were very few strong pro-slavery voices in the movement, and while there were a few more abolitionists, those voices were also a rather small minority. Perhaps most importantly, the movement’s center was occupied by people who were pacifists by religious conviction and who had a strong belief that the church, not politics, was the key to societal reform. And they had a strong commitment to movement unity. Why, then, did the movement divide anyway?

It divided, I believe, because eventually, a sufficiently large number of northern members decided that their moral principles – which were informed by the political currents of the time – were too important to continue sacrificing for the sake of an elusive unity. If slavery was evil, Christians could not continue to tolerate slaveholders, as Campbell wanted. And they especially could not tolerate those who took up arms against their government. The conservatives, in turn, could credibly claim that the northern Disciples faction had abandoned a historic tenet of the movement when it came to the church’s relationship to war and politics, and that they could not tolerate this deviation from the pacifist teachings of Jesus. In embracing the cause of social reform through the Civil War, northern progressives had embraced the ethic of violence, which violated the teachings of the Sermon on the Mount. Both sides thought the other group were heretics.

Perhaps the “young, restless, and Reformed” movement is on the verge of entering similar territory. For the last twenty years, the movement has condemned racism and emphasized interracial coalitions, but has also leaned toward political conservatism. It has also promoted a social vision that has emphasized the work of the church far more than any earthly reform-minded political coalition. On the most conservative end were those who (like John MacArthur) said they opposed social reform movements altogether, and on the progressive end were people like Tim Keller who said that the church was called to embrace social justice. But even some of the most politically progressive people in the movement tended to believe that the church, not a political party, should be the instrument of social justice campaigns. There is thus perhaps an understandable dismay among the conservatives to see their progressive counterparts embrace a secular movement such as Black Lives Matter or vote for Democratic candidates who support abortion rights – despite the movement’s longstanding and uniform condemnation of abortion. It is as though, in the eyes of the conservatives, they were betraying some of the foundational tacitly understood beliefs of the movement and turning their backs on the unborn – just as, in the eyes of the progressives, the conservatives were abandoning the interests of their Black brothers and sisters and imbibing a toxic brew of anti-immigrant, Christian nationalist bile.

But why did this split not occur earlier? Why, in the 19th century, could Lipscomb, Garfield, and Campbell remain in the same movement without rancor in the 1850s, only to decide in the 1860s to part ways? Why could the “young, restless, and Reformed” coalition easily hold together without partisan bickering in the first decade of the 21st century, only to become strained in the second decade and on the verge of a permanent fragmentation in the third? I think that the answer is that the moral causes that splintered the movement did not seem so important and obvious to either side in the movement’s early years. In the 1850s, some Restorationist Christians considered slavery a grave moral evil, but perhaps not quite so consequential an evil as they did after the Civil War began. Other Stone-Campbell Restorationists likewise considered political violence a serious sin, but they never dreamed that many of their brothers in the movement would embrace a call to arms until they actually did in the Civil War. Similarly, today, many Reformed evangelicals may not have considered political questions of race a dividing point until they became one in the larger culture. And many never dreamed that the Christians who sang the same songs and attended the same conferences would embrace the sort of politics they did in the Trump years – until they actually made those choices.

Larger national culture wars can divide the most apparently united and apolitical religious movements. It’s easy for Christians to claim that the church will rise above politics and offer a kingdom-centered vision that crosses party lines. But when moral issues are at stake, and Christians within a movement decide that their fellow brothers and sisters are making immoral political choices, whatever unity they once professed becomes remarkably hard to maintain.

I still believe that with the guidance of the Holy Spirit and a determination to resist the siren songs of the partisan slogans on both sides of a culture war divide, Christian unity can be maintained even among those with sharp partisan differences. But maintaining this unity will require a concerted effort to look past the political labels of the Christians on each side of a political divide and focus on the orthodox Christian principles that both groups are seeking to maintain even as they fight over significant political differences that cannot be ignored. The Stone-Campbellites failed to look beyond the partisanship a century and a half ago, and their movement therefore experienced a permanent fissure. Unless they make a conscious effort to forge a different path, the “young, restless, and Reformed” Christians may experience a similar division today.