This is going to be intriguing. In 2019, it was announced that the terrific director Yorgos Lanthimos (The Lobster, The Favourite) will be directing a version of Jim Thompson’s 1964 novel Pop 1280. I have no idea where that project stands in light of the current maelstrom in the movie industry, but I will be interested to see if and when the film does emerge. Apart from being one of my favorite modern novels, it is also an authentic American religious classic, and specifically, one of the great Southern novels. It has a lot to say about themes we think about so much today, including racial violence and systematic corruption.

You would not get that religious quality from quick descriptions of the movie project. According to Vulture, Pop 1280 “tells the story of a crooked sheriff trying to game the upcoming election for his position so he can maintain the small town’s ‘careful balance of criminality’.” Well yes, that’s accurate, but only in the sense that Dante’s Inferno is about a guided caving holiday in Italy.

Jim Thompson (1906-1977) was born in Anadarko, Oklahoma, the son of local sheriff Big Jim Thompson, and that last fact is more than biographical trivia. Diabolical sheriffs with dark secrets are central to Jim junior’s best writing. The younger Thompson floated between jobs in the 1930s, until he found his métier as a pulp novelist. He wrote disposable paperbacks commonly marketed with sensational pictures of scantily clad women and heavily-armed men. But some of those books were authentically brilliant, particularly The Killer Inside Me (1952). However bizarre the analogy might have sounded in his lifetime, Thompson today can properly be read alongside Flannery O’Connor, while French critics compare him to William Faulkner.

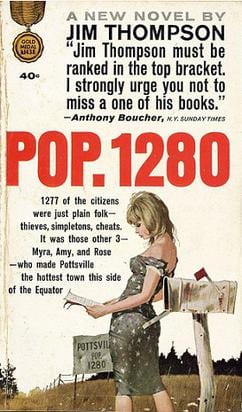

So what about Pop. 1280? The original book was marketed as a sensational and sexy thriller, and the cover bore the enticing description you see illustrated here: “It was those other three — Myra, Amy, and Rose — who made Pottsville the hottest town this side of the Equator.” I’ll come back to that “hottest” thing. It’s really a hell of a town.

Pop. 1280 includes some of Thompson’s most explicitly religious themes, although portions of it are so riotously funny that you may find it hard to believe that there is serious content: but indeed there is. Pop. 1280 has unsettling autobiographical overtones. It is the story of a claustrophobic small town named Pottsville around 1917, with its apparently hapless sheriff, Nick Corey. The setting sounds a lot like the real-life Anadarko of Thompson’s childhood. Although the title refers to the sign you see entering the town, “Pop” suggests the paternal theme. Jim’s real-life father, the sheriff, was an exceedingly smart and quite cultured man whose masquerade as a country boob allowed him to gain an enormous advantage over anyone who took his Barney Fife act seriously. Or to use another reference from that same Andy Griffith universe, Jim’s Pop was both as deceptive, and as dangerous, as the singer star of the brilliant 1957 film, A Face in the Crowd.

But Pop. 1280 is not just a historical work, written as it was at a time of the most intense racial violence against the civil rights movement. That gave leftist veteran Thompson a platform for his bitterest condemnations of small town racism and bigotry. (He claimed to have served as Secretary of the Oklahoma Communist Party back in the 1930s). It is the American South of 1964 that Thompson is damning to perdition. When French director Bernard Tavernier triumphantly adapted the novel into the film Coup de Torchon (“Clean Slate”, 1981), he moved the action to colonial French West Africa in 1938, in order to preserve the atmosphere of pervasive racial oppression.

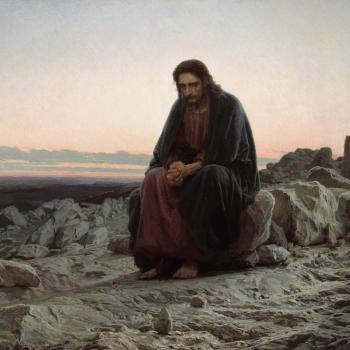

Coup de Torchon caught precisely the religious and apocalyptic tone of the book, an impressive feat for anyone not as immersed as Thompson was in the language and worldview of Bible Belt hellfire revivalism. Although we first meet Sheriff Nick as a comical loser, exploited and put upon by family and neighbors, he ultimately appears as a Miltonic or even biblical figure, sent as judge and executioner of an utterly evil society rotted by racism, hypocrisy, cruelty, and exploitation.

In his own messianic fantasy, Nick sees himself as Christ on the Cross, sent to Potts County “because God knows I was needed here.” At the same time, he is something between an avenging angel and the Native American Trickster. He gradually purges and slaughters the town’s sinners, using their own crimes and lusts in order to destroy them. After all,

“Just because I put temptation in front of people, it don’t mean they’ve got to pick it up …. I was just doing my job, followin’ the holy precepts laid down in the Bible …. It’s what I’m supposed to do, you know …. To coax ’em into revealin’ theirselves, and then kick the crap out of them.”

Only at the end do we fully comprehend Nick’s spiritual role, as a devil, if not The Devil. Old Nick is the sheriff of Potts County, a microcosm of the sinful world, in which he goes about as a roaring lion, seeking whom he may devour. But his victims are not individual sinners. As Nick says,

“There can’t be no personal hell, because there ain’t no personal sins. They’re all public … we all share in the other fella’s and the other fella shares in ours.”

The whole society demands purgation.

And why Potts County? As St. Paul told us in Romans, mere creatures have no right to protest against God’s will, however severe its effects might be. They’re just pots:

Hath not the potter power over the clay, of the same lump to make one vessel unto honor, and another unto dishonor? What if God, willing to shew his wrath, and to make his power known, endured with much longsuffering the vessels of wrath fitted to destruction? (Romans 9.21-22, KJV).

In that sense, we all live in Potts County.

According to your reading, Pop.1280 is an apocalyptic satire of America, a theological account of temptation and damnation, or a masterly case-study of religious mania. It might even be Jim Thompson’s riposte to Job. But however you take it, it transcends its pulp genre to become a religious classic.

So how much of that will come out in the film?

I just have an odd synchronicity to report. As I was completing this post, I read a National Review piece about a new edition of the letters of John Berryman, that wonderful Catholic poet. In the 1920s, his family lived for some years in Anadarko, where he was an altar boy at the local Catholic church. He was a few years younger than Thompson, and I have no idea if their paths ever crossed in that small city, but it’s fun to speculate.