I’m pleased to welcome Hillary Kaell to the Anxious Bench. She is an associate professor of anthropology and religion at McGill University and a faculty fellow at Concordia University’s Centre for Sensory Studies. She writes about North American Christianity, often focusing on how Christians make and imagine global connections. She is author of Walking Where Jesus Walked: American Christians and Holy Land Pilgrimage (New York University Press, 2014) and, most recently, Christian Globalism at Home: Child Sponsorship in the United States (Princeton University Press, 2020). What follows is a conversation we had last fall about child sponsorship. –David

***

David: When did child sponsorship begin?

Hillary: “Sponsorship,” as I define it in the book, is a charitable fundraising system that, at a basic level, asks individuals or small groups to support one “special object” abroad, as nineteenth-century people put it. The iconic ‘special object’ is definitely a child—although the same principle has been applied in other ways too. With that definition out of the way, the short answer is that North Americans were first introduced to sponsorship on a (relatively) large scale in about 1816, shortly after the first American Protestant foreign missionaries arrived in India and Ceylon (Sri Lanka). They were casting about for a good way to raise money fast, create long-term support for their schools, and inculcate global sentiments in home audiences. This kind of fundraising—which they called “adoption”—seemed to address each of those priorities.

In an interview with you, a Compassion executive talked about “Mrs. Jane Q Sponsor.” Who is she?

In an interview with you, a Compassion executive talked about “Mrs. Jane Q Sponsor.” Who is she?

“Jane” is a statistically typical sponsor. She’s a married white woman, usually with kids. Traditionally, and still in Christian organizations, she is also a committed church goer. She is often middle-class, but she can also be much less well off. That’s not too surprising, since sponsorship developed to encourage charitable donors among the poor and middle classes by offering them a chance to contribute just a little bit in regular instalments each month. Today, for example, sponsors usually pay $35 or $40 a month, which most people can afford. Sponsorship was never aimed at wealthy patrons who could give major bequests and donations. It’s also important that the Compassion exec said “Jane” and not “Joe.” From the start—way back in 1816—sponsorship was envisioned, in part, as a way for women and children to focus their ‘affections.’ Male fundraisers and missionaries thought (almost certainly incorrectly) that women couldn’t understand the abstraction of global connection without a specific individual on the other end.

Is child sponsorship a distinctively American activity?

Not at all. But it’s a distinctively Protestant activity, at least in its initial framing. Evangelical missionaries felt that children in their mission schools needed a rather lengthy formation until they were mature enough—as people and Christians—to profess Christ. Sponsorship—which, ideally, was a commitment to support one pupil until adulthood—created regular, long-term support. So the method of fundraising was specifically related to a Protestant theology of conversion. On that note, the other thing about evangelicals is they felt that a mature Christian (the donor) could “encourage” a potential convert or new Christian (the child) in faith, and this process could be accomplished through letters. This model comes from Paul’s letters in the Bible. Sponsorship, which always included some kind of exchange of letters, appealed to Protestants at that level too.

Today, sponsorship is much more widespread, of course. Catholic, Hindu, and Muslim organizations run child sponsorship plans; lots of Jewish or non-religious people have told me about sponsoring through non-confessional organizations like Save the Children. But we can still see the legacy of that Protestant affinity with sponsorship: more than half of the two hundred most significant programs are based in the Protestant-inflected societies of the United States and United Kingdom. Of the ten largest sponsorship organizations, five were founded in the United States, two in England, and one in Denmark, Austria and Germany, respectively. Most were started by Protestants.

How does participating in sponsorship give Christians a “pleasurable swept-up-ness”?

That’s a term from an article Melani McAlister wrote back in 2008—it’s so evocative that it stuck with me. Christian Globalism at Home suggests that a sensory approach to this material can help us better understand the multiple practices through which Christians at home feel their way into global connection. Visceral feelings—including joy and pleasure—drive people to keep giving. One of the reasons I like “swept-up-ness,” too, is that I argue that globally minded Christian sponsors are not only trying to create an intimate one-to-one connection with a child abroad. I found lots of evidence that they are just as intent on forging connections to something much bigger than themselves—the immensity of a God that is everywhere at once. Fundamentally, the book traces a necessary interplay between intimacy and immensity.

“Eat your dinner. There are starving children in Africa.” Why was this such an appealing adage for American Christians in the twentieth century?

I grew up with “Africa,” which it marks me as a child of the post-1970s. It was “Armenia” in the 1910s and 1920s and “China” in the 1930s. Readers probably know other versions too. The phrase is appealing to adults because it is aimed at disciplining their own children. And disciplining children—‘guiding them’ is perhaps a better way to put it!—to become globally minded is a major part of the impetus for child sponsorship. Especially over the twentieth-century, sponsorship has also provided a potent way for U.S. adults to talk to each other about child-to-child charity as a solution to global problems of war, politics, etc. Of course, significant scholarship has pointed out the problems inherent in any notion of charity or development work as devoid of politics.

Why do Christian sponsors like statistics and audits so much?

Christian donors are no different from other donors in North America or Western Europe—we all like statistics and audits! Our collective love affair with audits speaks to the problem of trust inherent in a capitalist economy, including its charitable manifestations. How do you know that your money is going where brokers say it will go? That issue is especially pertinent in global projects, where you can’t see the result of your giving. It gets at the moral difficulties in capitalism, which is one theme that runs throughout the book. What does differ about Christians who give to Christian organizations, however, is that many of them use multiple forms of ‘audit’ in order to assure themselves of God’s presence in the process. In terms of statistics, my interest is a bit different. I am more focused on the “aesthetics” of statistics, that is how displaying big numbers and an accumulation of things can make people feel swept up in immensity.

How did orphan sponsorship and adoption reflect a desire for kinship and racialized unity?

In discussing “racialized unity,” I underline how images of global togetherness generally use ‘race’ as a signpost. In Christianity, for example, there are iconic images of the “nations” (often pictured as children) gathered around Jesus. Although such images seem to transcend dichotomies between “us and them,” they pack an emotional punch precisely because they are couched in an unspoken legacy of assumptions about the ‘natural’ segregation of races. For Christians, these images therefore seem to testify to the miracle of God’s ability to unite and override ‘natural’ differences—even to the point of creating in them a kin-like longing for, and relatedness with, Asian or African children.

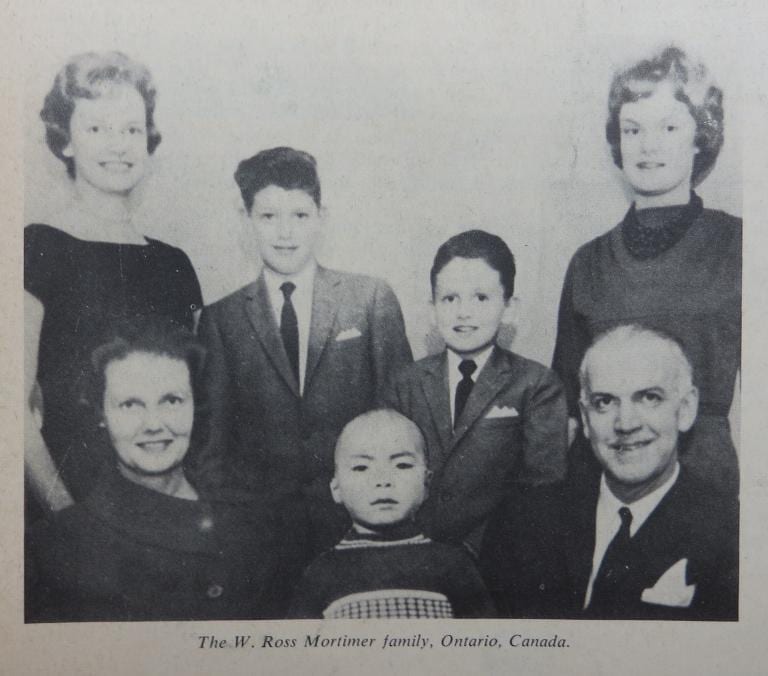

Sponsorship is a great example of how intimate and immense scales reinforce each other. Big hopes for global racial unity are lived at the intimate level in those ‘kin-like’ longings. And the intimate connections donors create with the child, for example by reading his letters aloud or praying for him at the dinner table, cultivate a sense of global unity. As I noted above, I’m especially interested in the sensory, practical dimensions of imagined connections. For example, in the book I included a photo of the Mortimer family. In 1962, they posed for a family portrait but left a space in the middle. After printing the photo, they cut out a photo of the Korean child they sponsored and pasted it the gap. They kept a copy of this ‘complete’ family portrait and sent one to the child and one to World Vision—where I found it a generation later.

I definitely don’t want to dismiss sponsors’ yearnings for kin-like connection and global unity, since they are very real. But it’s also important to note that this imagery—whether made by organizations or families like the Mortimers—has generally been created by and for White people. As a result, it has subtly reinforced a view of White people as endowed with the capacity to create charitable networks and, ultimately, lead humanity forward.

I definitely don’t want to dismiss sponsors’ yearnings for kin-like connection and global unity, since they are very real. But it’s also important to note that this imagery—whether made by organizations or families like the Mortimers—has generally been created by and for White people. As a result, it has subtly reinforced a view of White people as endowed with the capacity to create charitable networks and, ultimately, lead humanity forward.

What surprised you most in your research?

The whole scope of the project was a surprise! I’d read a lot about sponsorship before beginning and it all pointed back to Save the Children, just after World War I. Although it was linked to the Quakers, Save the Children was not a ‘religious’ organization per se. So my assumption was that sponsorship exemplified how Christian entrepreneurs in the 1930s-1950s picking up a humanitarian model and mobilizing it for their own audience. It fit with the story that we often tell about neo-evangelicals like Billy Graham who were so adept at deploying popular culture; in fact, Bob Pierce, who started World Vision, was a buddy of Graham’s. But once I went to the archives, I realized that there were actually dozens of other organizations doing sponsorship during the war—a few years before Save the Children. And even more interestingly, some of them had missionary ties. So I started to pull the thread and it brought me back more than a century before I expected.

What are you working on now?

Well, the pandemic has closed the Canada-U.S. border, which means my research plans are on hold for the foreseeable future…! So maybe I can just mention something I’m working on now that is related to this project. As I was writing the book, I kept mentioning places outside the U.S.—I cover dozens of locations—but could never really explore them in depth. I’m also aware that we, North American scholars of the United States, don’t read enough work by our colleagues overseas, especially if they are outside of Europe and Australia. There are a number of reasons for that and I do think we’re getting better at recognizing the problem. So I wanted to find a way that this book could help further that discussion. Though it was a bit nerve-wracking, I “cold called” scholars in some of the locations I cover in the book and then I sent each one a chapter, related to their area, and asked them to use it as a jumping off point to discuss their own work and perspective. It’s a wonderful group—scholars from India, Hong Kong, Singapore, South Africa, and Turkey—and we’re going to publish the collaboration in American Religion, online and in print. I’m excited to highlight their work, and I hope the collection could also be a kind of object lesson to prompt discussion, particularly among graduate students, about methodology and power dynamics in our field.