Even in the 75th anniversary year of the atomic bomb, December 22nd might seem like an odd day to blog about Hiroshima. But I’ve got two reasons for today’s topic. I’ll come back to the theological one, but let’s start with the practical rationale:

Last week I read Lesley Blume’s new book, Fallout, which recounts how John Hersey went to the first of Japan’s two “atomic cities” in May-June 1946, interviewed survivors, and published a 30,000-word article that stands as a landmark of American journalism. Making up the entire August 31, 1946 issue of The New Yorker, “Hiroshima” was a sensation: the magazine soon sold out, and readers had to find black market copies until Alfred Knopf rushed out a book version later in 1946. It’s been in print ever since.

Last week I read Lesley Blume’s new book, Fallout, which recounts how John Hersey went to the first of Japan’s two “atomic cities” in May-June 1946, interviewed survivors, and published a 30,000-word article that stands as a landmark of American journalism. Making up the entire August 31, 1946 issue of The New Yorker, “Hiroshima” was a sensation: the magazine soon sold out, and readers had to find black market copies until Alfred Knopf rushed out a book version later in 1946. It’s been in print ever since.

Borrowing a device from Thornton Wilder’s novel, The Bridge of San Luis Rey, Hersey told his story through the eyes of six eyewitnesses he had interviewed in Hiroshima. Remarkably, three of the six were Christians, though less than 1% of the Japanese population followed Christ: about 200,000 Protestants and half that many Catholics.

That he disproportionately represented Christian perspectives was something of an accident. Though Hersey was born in China to YMCA missionaries, an upbringing that Blume says instilled in the reporter “his reserve and pronounced moral compass… along with his staunch aversion to self-promotion,” she adds that he wasn’t religious himself. But in preparation for his trip to Japan, Hersey had come across an account of August 6, 1945 written by a Jesuit philosophy professor, John Siemes: “The river banks covered with dead and wounded, and the rising waters have here and there covered some of the corpses. On the broad street in the Hakushima district, naked burned cadavers are particularly numerous.” Siemes’ story led Hersey to the Jesuit mission in Hiroshima, whose head, Hugo Lassalle, remembered thinking that morning, “This is the end of me. Now, I will know what it’s really like in heaven.”

(The Jesuits had first come to Japan in the mid-16th century, thanks to the pioneering mission of Francis Xavier. But a vicious wave of persecution led to the martyrdom of dozens of Jesuits and drove the country’s few remaining Catholics underground. The Jesuits returned to Japan in 1908 and founded Sophia University five years later.)

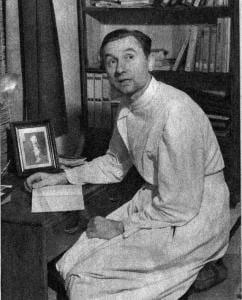

Hersey met a 39-year old German missionary named Wilhelm Kleinsorge, whose minor initial injuries had refused to heal. As the days and weeks went on, he suffered from fatigue, fever, nausea, and other symptoms serious enough to have him sent to the Catholic hospital in Tokyo, where he overheard a doctor tell the Mother Superior, “All these bomb people die.”

Kleinsorge survived to recount for Hersey how he had been reading a Jesuit magazine in his underwear when the bomb dropped that August morning. He blacked out and woke up to find himself staggering around the mission’s garden. He and other priests gathered in Asano Park, where they would try to assist the city’s shocked survivors. Carrying water to and from the park, he came across twenty soldiers, “all in exactly the same nightmarish state: their faces were wholly burned, their eyesockets were hollow, the fluid from their melted eyes had run down their cheeks.”

Kleinsorge then served as Hersey’s translator and introduced him to two more Christian eyewitnesses. First, a Methodist pastor named Kiyoshi Tanimoto, a Buddhist convert to Christianity who had studied at the Candler School of Theology and spoke English fluently. (Suspected of sympathizing with Japan’s enemy in World War II, Tanimoto chaired his local neighborhood association and organized its air raid defense.) Worried that “the Americans were saving something special for” Hiroshima, the pastor had sent his wife and infant daughter to a house in the suburbs and begun to move Bibles, records, and even the piano and organ from his church to a businessman’s summer home. That’s where he was when the bomb detonated above the city center and he saw the nightmarish immediate effects (as summarized from his testimony by Hersey):

The eyebrows of some were burned off and skin hung from their faces and hands. Others, because of pain, held their arms up as if carrying something in both hands. Some were vomiting as they walked. Many were naked or in shreds of clothing. On some undressed bodies, the burns had made patterns—of undershirt straps and suspenders and, on the skin of some women (since white repelled the heat from the bomb and dark clothes absorbed it and conducted it to the skin), the shapes of flowers they had had on their kimonos.

Tanimoto somehow found his wife and child in the wreckage, then joined Kleinsorge and the other Jesuits in helping survivors along the river. “As a Christian he was filled with compassion for those who were trapped,” explained Hersey, “and as a Japanese he was overwhelmed by the shame of being unhurt, and he prayed as he ran, ‘God help them and take them out of the fire.’” Tanimoto found a small boat and removed its five dead passengers. (“Please forgive me,” he told them. “I must use it for others, who are alive.”) In Blume’s description, the pastor used the craft “to transport gravely wounded survivors to the opposite bank like Charon ferrying the souls of the deceased across the river Styx.”

Tanimoto became the best-known of the six eyewitnesses in Hiroshima (and the co-translator of its Japanese edition). He spoke out against nuclear weapons, raised funds for reconstructive surgeries for survivors, and even prayed in the U.S. Senate in 1951. (“We thank Thee, God, that Japan has been permitted to be one of the fortunate recipients of American generosity.”) Blume also recounts his awkward experience on a 1955 episode of This Is Your Life, when the producers not only flew in Tanimoto’s wife and daughter, but introduced him to the captain of the plane that had dropped the bomb.

But Hersey’s story doesn’t open with Reverend Tanimoto or Father Kleinsorge. Instead, its famous first paragraph started with a 20-year old woman who was not a Christian at the time:

At exactly fifteen minutes past eight in the morning, on August 6, 1945, Japanese time, at the moment when the atomic bomb flashed above Hiroshima, Miss Toshiko Sasaki, a clerk in the personnel department of the East Asia Tin Works, had just sat down at her place in the plant office and was turning her head to speak to the girl at the next desk.

Sasaki lost her parents and infant brother and was still recovering from her own injuries when Hersey interviewed her. Crushed beneath falling bookshelves, Sasaki found shelter in the Goddess of Mercy Primary School. Her left leg wasn’t set properly and was three inches shorter than the right when Father Kleinsorge met her in the hospital in February 1946. Hersey reported their exchange about the problem of evil:

She asked bluntly, “If your God is so good and kind, how can he let people suffer like this?” She made a gesture which took in her shrunken leg, the other patients in her room, and Hiroshima as a whole.

“My child,” Father Kleinsorge said, “man is not now in the condition God intended. He has fallen from grace through sin.” And he went on to explain all the reasons for everything.

(While Hersey only mentioned Nagasaki in passing, a Catholic survivor of that second atomic attack, radiologist Takashi Nagai, described his experience in The Bells of Nagasaki. Historian John Dower observed that “Nagai’s message bordered on the mystical. Essentially, he regarded the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki as the act of a Christian God meant to bring the world to its senses.” Some of his countrymen “found such religious fatalism unpalatable, not to say fatuous, but even they could not deny Nagai’s contribution to the swelling of pacifist sentiment in Japan.” Nagai died of leukemia in 1951.)

Kleinsorge’s explanation, noted Blume “must have been convincing: that summer, in 1946, Miss Sasaki decided to convert to Catholicism.” She helped to start an orphanage a year later and took vows as Sister Dominique Sasaki in 1957. Indeed, Father Siemes claimed that the relief work done in the immediate aftermath of the bombing was, “in the eyes of the people, a greater boost for Christianity than all our work during the preceding long years.”

For his part, Wilhelm Kleinsorge later became a Japanese citizen, taking the name Makoto Takakura. “When Hiroshima was destroyed,” he explained, “I became determined to become Japanese… I want to remain forever in Hiroshima, as an instrument of God’s will.” Before he died in 1977 (as a “living corpse,” according to a note in his hospital chart), he claimed only to read the Bible and railway timetables, since they were “the only two sorts of texts… that never told lies.”

That was one of the details Hersey learned when he returned to Hiroshima in 1985 for a follow-up article. But that same year, he also published a novel called The Call. Based on the experience of Christian missionaries like his father, it questioned the effectiveness of the entire mission enterprise in Asia.

Hoping to stem the spread of Communism, Gen. Douglas MacArthur had openly celebrated the American occupation of Japan as “an opportunity without counterpart since the birth of Christ for the spread of Christianity among the peoples of the Far East.” But while the occupation czar opened the door for hundreds of Protestant and Catholic missionaries and millions of Bibles to come to Japan, conversion stories like Toshiko Sasaki’s remained unusual. After six years of occupation, the number of Japanese Catholics had grown by just 50,000, while the Protestant figure had only recovered to where it was before the war. To this day, less than 1% of the Japanese population is Christian.

But while Japanese pastors like Kiyoshi Tanimoto and Western missionaries like Wilhelm Kleinsorge made few disciples in that nation, they and Toshiko Sasaki did succeed in fulfilling a basic mission of Christians at all times and in all places: to bear witness to the truth.

Un-Christmas-y as it may sound, I’m glad I revisited the terrible story of Hiroshima just before the wondrous story of Jesus’ birth. For how else can we truly hear the angels’ announcement of peace on Earth if we don’t understand the most profound absence of peace that humans can imagine and inflict?

So let me close with this English translation of Pope John Paul II’s closing prayer at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial in February 1981:

Hear my voice, for it is the voice of the victims of all wars and violence among individuals and nations;

Hear my voice, for it is the voice of all children who suffer and will suffer when people put their faith in weapons and war;

Hear my voice when I beg you to instill into the hearts of all human beings the wisdom of peace, the strength of justice and the joy of fellowship;

Hear my voice, for I speak for the multitudes in every country and in every period of history who do not want war and are ready to walk the road of peace;

Hear my voice and grant insight and strength so that we may always respond to hatred with love, to injustice with total dedication to justice, to need with the sharing of self, to war with peace.

O God, hear my voice and grant unto the world your everlasting peace.