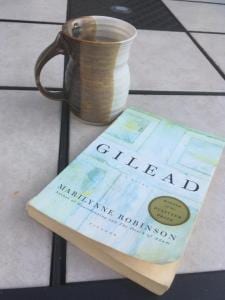

It’s time to reread Gilead.

Last week’s release of Marilynne Robinson’s new novel about the characters she introduced in Gilead is more than a publishing development. Addressing in fiction a past painfully relevant to our own, the book’s coming counts as an event in its own right. When excerpts of Jack started leaking out during the summer’s hot days of anguish over racial violence, sickness, and fear, I could hardly wait. But now I am not sure if I can bear it, the beauty of Robinson’s prose, the way she uncovers grace in people and things. I am also not sure I am ready for what the book might reveal or close off. To be clear, then, I have not yet read Jack at this writing.

Rereading Gilead is a good way to advance toward reading Jack. Robinson’s titular character is lonely, isolated, shamed, blameworthy, charming, beloved, and hard to rescue. When, a decade or so ago, my book group took up Robinson’s earlier novels, I thought we would plumb the mystery of this character, Jack Boughton. No revelation came: the group, careful readers who were mostly in counseling and social work, delivered their quick consensus that Jack had anhedonia, undiagnosed because the setting put young Boughton in a time and place before prescription medicine could have helped him.

Of course, there is more to it than that.

Though found on no map, Gilead, Iowa, is a place to sit in for while, even as we sit in the present moment where we are stuck. The book’s narrator, Rev. John Ames, carries memory of the pandemic of 1918 as he observes his town:

“People don’t talk much now about the Spanish influenza, but that was a terrible thing….It was like a war, it really was….People came to church wearing masks, if they came at all. They’d sit as far from each other as they could. There was talk that the Germans had caused it with some sort of secret weapon, and I think people wanted to believe that, because it saved them from reflecting on what other meaning it might have….

“It is hard to understand another time. You would never have imagined that almost empty sanctuary, just a few women there with heavy veils on to try to hide the masks they were wearing, and two or three men. I preached with a scarf around my mouth for more than a year. Everyone smelled like onions, because word went around that flu germs were killed by onions.”

Now many church sanctuaries are empty, or at least are emptier than usual. It is a policy that feels strange for institutions oftener expecting to draw people in, to welcome them; now showing love-to-neighbor comes by limiting access, requesting advance booking for attendance. No one tries to hide their masks.

(And, parenthetically, that last bit about the onions strikes me, since onions trouble this stage of my pandemic experience. In March I lost smell and taste for a month, suspected Covid but not tested. My senses mostly came back but some things still smell wrong. Onions are worst, with metallic pungency and a kind of sick sweetness.)

Some of Gilead’s central action turns around the redress of race-based injustice, by people ancestrally committed opposing race-based injustice but unable quite to remake the world or themselves to the degree necessary to enable an ordinary life for Jack and his wife Della, who is Black, and their son. As Elaine Showalter writes of Robinson’s new book in a New York Times review, “the Gilead books are unified as well by [Robinson’s] unsparing indictment of the American history of racism and inequality, and Christianity’s uneven will to fight them.”

That “uneven will” is not only a matter of half-heartedness but of principled disagreements about means. Even when the high-minded and pure-hearted array themselves against racism and inequality, things can go awry and they can inflict damage. Generational conflict threaded through Gilead sees competing goods reach impasse, movement on racial justice coming against pacifism. The narrator’s grandfather, Union-pledged, Kansas-fighting abolitionist preacher of a John Brown stripe—“the most unreposeful human being I ever knew”– contends with his son, a pacifist convinced that violence violates the Gospel. (This conflict Robinson shows by means of a handmade needlework hanging over the communion table, decorated with “flowers and flames” highlighting its message, “The Our God is a Purifying Fire,” which, when the pacifist son tells a church lady that the line is not in scripture, draws from her the retort,”Well…then it certainly ought to be.”)

People intently can want the good, and even be right about the good, but can utterly botch the means of securing it—as demonstrated in Gilead by the account of a “forgotten little abolitionist settlement” nearby. Its citizens aimed to serve the Underground Railroad by building a tunnel (“Tunneling was a popular activity at that time”), only to have the tunnel draw unwanted attention by collapsing under a visiting horseman. This sent a young man, who was likely fleeing enslavement, to get out as fast as he could: “I thank y’all kindly, but I think I best do this on my own.”

Letting white-hot passion for justice cool down has its dangers too. Jack, seeking pastoral care from Rev. Ames, asks whether his family, with his Black wife and child, could safely live in the town. Ames assures him so. But then he wakes up a few mornings later “thinking that this town might as well be standing on the absolute floor of hell for all the truth there is in it.” Thinking through all that had happened, environmental destruction and pandemic and economic hardship and war, Ames observes that even well meaning people “became like people who didn’t know their right hand from their left,” complacent after the “heat of an old urgency” was forgotten, having lost “courage and passion,” left “awkward and ridiculous.”

I am looking forward to reading Robinson’s Jack, though I am not ready yet. Some readers might take a while to be ready: The-promotional leaflet at my public library checkout desk warns that Jack “will not be for every reader. First of all, it’s a slow read,” though, the reviewer concedes, the moral freight of the not “vigorous” plot requires a bit of reflection. That it does.

Robinson’s stories are worth reading slowly, rereading slowly, maybe now more than ever, because of something else that Rev. Ames notes: “When things are taking their ordinary course, it is hard to remember what matters.” We are far out of ordinary course. Perhaps we can remember better.