In the classic romantic comedy When Harry Met Sally, Harry famously asserted, “Men and women can’t be friends because the sex part always gets in the way.” The popularity of the “Billy Graham rule”—that a married man should never be alone with a woman who is not his wife—would seem to indicate that many Christians today agree.

This summer I’ve enjoyed participating in a discussion group on male-female friendships in the American church that challeng ed that proposition. Fellow participants all work at Baylor, but range across various departments and student life. All identify as broadly evangelical, but worship in different types of churches. And all agree that these friendships are both essential and culturally fraught. We wanted to think through the challenges and how we can encourage better mixed-sex friendships in the church.

ed that proposition. Fellow participants all work at Baylor, but range across various departments and student life. All identify as broadly evangelical, but worship in different types of churches. And all agree that these friendships are both essential and culturally fraught. We wanted to think through the challenges and how we can encourage better mixed-sex friendships in the church.

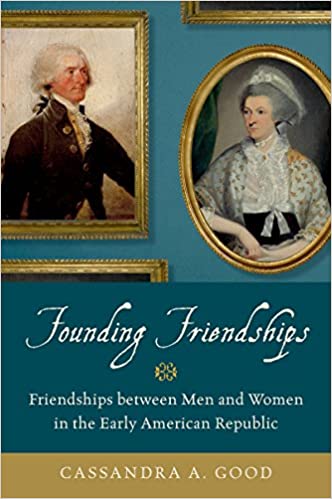

The group also made my historian heart happy: someone from another field proposed we center the conversation on Cassandra Good’s book Founding Friendships: Friendships Between Men and Women in the Early American Republic. Examining what mixed-sex friendships looked like in a past culture casts into sharper relief the strengths and weaknesses of our present culture.

Conversation produced a wealth of theological, cultural, and practical reflection. I therefore asked a couple participants to share some brief written reflections. Their thoughts reflect their different disciplinary approaches and the different church environments they have inhabited. I’ve included my own thoughts at the end.

Ian Gravagne, Electrical and Computer Engineering (Ian noted that this might be his first time writing something without an equation in it!):

Christians who openly nurture meaningful opposite-gender friendships will not get far before the whispering starts: You’re playing with fire. He thinks he can tip-toe right up to line without crossing it? Those two are one step from becoming lovers. This can only go two ways: family or fornication! The list goes on, and the message is clear: befriending the opposite sex is too… risky.

Founding Friendships examines the idea of risk throughout, noting that the friends often bore risks (e.g. to reputations through gossip) that were substantially elevated compared with today. Some potential risks have not diminished with time; for example, Good examines the risk of misunderstandings about the emotional character of the friendship. But what exactly is risk in this context?

Risk, properly stated, always consists of two parts: a probability of an undesirable outcome and a cost associated with that outcome. In many fields, risk is stated with numerical precision, for example, “There is a 1% chance of a flood causing $100m worth of damage each year.” Sometimes the cost is implied, such as, “There is a 1-in-5 chance of developing breast cancer in your remaining lifetime.” (The potential costs of cancer being understood to include money, suffering, and possibly death.) The whispered critiques above are essentially statements of risk, and because the implied costs are moral in nature church leaders often espouse rules that they believe will nullify the probability part of the risk equation.

Overlooked in their well-meaning but short-sighted guidance, however, are three essential facts about risk: First, there is no such thing as zero risk in any meaningful human activity. In fact, we accept risk in virtually everything we do. If you drive a car, you have accepted some risks with potentially large costs, including death. Human beings were created to be in relationship with each other and with our Creator. Where there are relationships, there is more risk. Jesus engaged in close relationships with women, accepting many of the same risks as the friends in Founding Friendships. Why? Because, second, we accept risk in order to obtain something valuable! Rationally, the men and women in Founding Friendships would not have carried on but for the value they found in friendship, including intellectual fulfillment, companionship, services (especially for women), and others Good examines in wonderful detail. Third – a point that cannot be overstated and warrants an essay all its own – reducing the cost of a particular risk often simply displaces that cost to another place, person or group. (Could it be that relational risk aversion is partly behind the growing loneliness epidemic in America?)

Good suggests that we suffer both a deficiency of language and of imagination in building caring and close friendships across gender lines. I agree, and submit that our Christian tradition and theological framework offers a third way, a path forward for opposite-gender friendship to grow neither toward family (necessarily) or fornication but toward spiritual union – a kind of love that defies easy categorization but can be deep, abiding and fulfilling. In part, I think this is what scripture suggests with language about “brothers and sisters”. If we have been set free from the bondage of sin, are we free to trust and affirm one another instead of viewing the other as a risk? Are we free to invite the Holy Spirit to be an ever-present third person in the relationship, helping to work through misunderstandings and avoid temptations? Can we see our friends as God sees them – not as calculated risks, but as eternal, created beings with value that transcends gender or appearance? (Are we free to even talk about these ideas in typical church culture?) These are complex questions, but many of the founding friends answered them with a resounding YES – over 200 years ago!

Lori Kanitz, Institute for Faith and Learning (Check out Lori’s new book on the theology of Annie Dillard!):

I bought a chest freezer this past weekend. I did so because my friend—I’ll call him Richard—who is a self-defined “prepper” has been dogging me lately to prepare better for the unknown pandemic terrain. Richard and I met in eighth grade art class when one day he snuck his monster drawings down the row to me. That was over forty years ago. He has been happily married for years and has a family now. I married my work. Yet Richard remains my friend and for the same reasons we became friends at thirteen. He’s simply one of the most interesting, funny, and kind people I know. I have learned a lot from him.

I imagine (and hope) many people have similar stories of enduring and significant heterosocial friendships—fulfilling, formative friendships with a person of the opposite gender with whom one is not romantically involved. Yet heterosocial friendship is hard to find and even harder to defend in a culture, particularly Christian culture, that assumes men and women who share a deep connection will inevitably stray into forbidden territory either emotionally or sexually. To insist otherwise is thought to be naïve or disingenuous. “We’re just friends.” Sure, you are.

As Cassandra Good points out in Founding Friendships, unfortunately this leaves us with neither the imaginations nor the nuanced vocabulary needed to describe and create the sorts of friendships that are extraordinarily important to human well-being, particularly in times of crisis or profound change. In the early Republic when old social systems (e. g. monarchy, aristocracy) simply no longer existed, friendships between educated men and women became crucial to forming a new social order: they “expanded an individual’s networks beyond marriage and family, offering new sources of affection, intellectual exchange, and practical assistance” (6).

Interestingly, these sentiments appear nearly verbatim in Mandy Len Catron’s July 18 article in The Atlantic, “There is So Much More Than the Nuclear Family, Even Now,” as she reflects on friendships not in the early Republic but in the current pandemic. Americans have idealized the nuclear family, despite data that shows only about twenty percent of us actually live in one. Crisis exposes the fragility of that structure and the vulnerability of those outside it, but also creates opportunities for new social infrastructures that we might previously have avoided or decried. Suddenly the old rules defining hospitality, family, neighbor, and, yes, friendships, get suspended in the acuteness of immediate need.

This may be friendship’s moment. At least I hope so. Despite the daily horrors of the pandemic, it is creating new categories, or perhaps resurrecting forgotten ones, for all the beautiful, creative, and multi-faceted ways we can love and care for others. As a university educator I have long wished for a new lexicon to name the infinite ways my students can enjoy friends of the opposite gender without marrying them or hooking up with them. I long for the same among my Christian brothers and sisters. How much richer would our lives in Christ be if we could learn to give and receive the gift of heterosocial friendship wisely but without fear and censure? What if we all had a “Richard” or two more in our lives? In my experience, they would be infinitely richer.

Andrea Turpin, History:

In one chapter, Good analyzes three pairs of “Founding Friendships”: Abigail Adams and Thomas Jefferson—who need no introduction—schoolteacher Eloise Payne and minister William Ellery Channing, and schoolmistress Mary Pierce and lawyer Charles Loring. (The friendships Good analyses tend to be among relatively well-off white women and men because they are the ones who most often left behind extensive personal correspondence.)

What struck me about these friendships is that they were essentially egalitarian within a hierarchical world. Women were legally and culturally subservient to their husbands in the early American republic, women could not vote or hold political office, and women did not have access to the same educational and vocational opportunities as men. Yet both men and women sought out friendships in which they could relate as equals. The fact that both parties could opt in or out at will made this dynamic possible.

Good highlighted something else I think particularly relevant to healthy friendships in the church today: the mixed-sex friendships that worked best tended to be between people not pigeon-holed into extreme gender roles. Male and female friends valued the different perspective they each brought to the table because of their gender, but they also valued each other as individuals and had enough common traits and experiences on which to base their connection. Here is Good:

What was it that made these close friendships with the opposite sex work?….[T]here are several common characteristics of these pairs that may apply in varying degrees to other pairs of friends. Perhaps most notably, Thomas, William, and Charles were all described by people who knew them as somewhat feminine. In the context of the time, this did not refer to sexual proclivities, but to a softness of demeanor, empathy, and an ability to connect with women…..[F]eminine qualities did not necessarily detract from manhood. The women, in turn, all had unusually sharp intellects that perhaps went beyond the intelligence thought becoming to a republican woman.

These particular men and women, and perhaps others who became friends, pushed at the edges of standard manhood and womanhood in ways that were ultimately compatible. A woman with a “mannish” intellect and a man with a “feminine” demeanor could be a natural fit as friends. All three of these pairs of friends shared common interests, whether in children, politics, education, religion, or even the outcome of a romantic relationship [with someone else]. In some ways, these men and women were much more alike than different: intelligent, frank, strong-willed, and in need of friendship. Mutuality, reciprocity, and emotional connection overcame gender difference (36).

Bringing these insights into today’s church, it would seem that the benefits of male-female friendships are easier to experience in church cultures that do not rigidly segregate men and women or rigidly stereotype their respective characteristics. Indeed, anecdotally in our discussion group, such friendships were more common and accepted in church cultures where the sexes aren’t as culturally segregated (mostly my experience) than in contexts where they are (the experience of some others in the group).

And what are the benefits of mixed-sex friendships? Men and women bring different experiences to the table. One of the implications of God making us male and female is that by definition no one person can have the complete human experience. We are forced into community. But a spouse cannot carry all the weight of providing the opposite sex’s perspective. We are not only male and female; we are also individuals. And many of us are single. The marriage bond is special and sacred, but church communities flourish more when women and men warmly cooperate in other ways as well.

PS: I have not read it yet, but evangelical theologian Aimee Byrd wrote what looks to be a good book advocating for mixed-sex friendships in the modern church. This summer, Aimee became the target of disdain from an online community of men in her denomination for challenging the rigid subcultures of men and women within it, even though she holds to her denomination’s theology of gender difference. Her experience adds evidence for the proposition that male-female friendships flourish better in church cultures that value women’s and men’s different perspectives without forcing them into narrowly defined subcultures.