An article printed last year in Christianity Today posed the following question: Do demons actively work to destroy marriages? Here’s how Chad Ashby, a Southern Baptist pastor from South Carolina, set up “Keeping Satan’s Fingerprints Off of Your Marriage”:

It was pitch black as I rode in the back of a safari vehicle, the headlights trying their best to cast a beam down the rocky path through the African bush. In the driver’s seat, a soft-spoken missionary was opening up about difficulties in his marriage: “Sometimes I’d be talking with my wife from another room, and she would burst out in tears. When I came around the corner and asked her face-to-face why she was upset, she said she had heard me say something deeply insulting. The problem was the words she had heard weren’t even close to the words I’d said. After it happened several times, we realized something demonic was going on.” As I listened, a question dawned on me that I’d never entertained before: Do demons actively work to destroy marriages?

So what made Ashby suddenly consider a possible connection between marriage and demons? I would suggest that it partly had to do with the enchanted setting of the African bush. Far away from home and feeling vulnerable while driving down a rocky path, Ashby was sensitized to supernatural realities he perceived to be swirling in and around him.

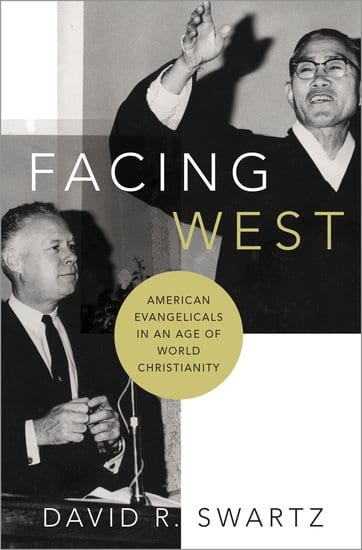

As I describe in Facing West: American Evangelicals in an Age of World Christianity, Ashby represents a much broader trend in the twentieth century. On one level, many evangelicals felt a profound dissatisfaction with what they perceived as a spiritually arid West. David Shibley, director of missions for the charismatic Church on the Rock in Rockwell, Texas, explained that the explosion of Eastern religions and the occult in America proved that “our sterile technology has created a thirst for metaphysical experience.”

As I describe in Facing West: American Evangelicals in an Age of World Christianity, Ashby represents a much broader trend in the twentieth century. On one level, many evangelicals felt a profound dissatisfaction with what they perceived as a spiritually arid West. David Shibley, director of missions for the charismatic Church on the Rock in Rockwell, Texas, explained that the explosion of Eastern religions and the occult in America proved that “our sterile technology has created a thirst for metaphysical experience.”

American Christians, these critics suggested, were products of their own context. Fuller Theological Seminary’s Charles Kraft, a missiologist and anthropologist, explained that Americans had inherited a deistic, mechanistic view of the world from rationalists such as Isaac Newton, Jean Jacques Rousseau, and Thomas Jefferson. This worldview allowed for the possibility of the supernatural but functionally left God out of everyday life. Filipino social anthropologist Melba Maggay contended that the West was “just as culture-bound” as the non-West. In combining Enlightenment thought and Christianity, wrote Lesslie Newbigin, a missionary to India, American evangelicals were “just as syncretistic” as African Christian polygamists. They were puppets of their rationalistic worldview.

At the same time, evangelicals traveling abroad observed an invigorated supernaturalism in the East. Paul Long, a Presbyterian missionary to the Baluba people in Congo, described demonic power at a spirit mound. “When I stood to speak, I felt the oppressive presence and power of overwhelming evil. The utter darkness was suffocating me. I felt the cold fingers of death press around my throat and I could not speak. As I stood there in foolish helplessness, the medicine people laughed; it sounded like voices from hell.” Long, who became a professor of missions at the Reformed Theological Seminary in Jackson, Mississippi, represented tens of thousands of missionaries who returned home telling supernatural tales.

Another missionary, having lived in both the United States and Nigeria, wondered if his rationalistic sensibilities meant that he was “teaching with one hand behind [his] back.” In their gloomiest moments, some missionaries even worried that they were colonizing enchanted villages in Africa with functional atheism. At the very least, Western rationalism suddenly seemed anomalous when viewed through the lens of world Christianity.

The list of American evangelicals who moved toward more supernatural discourse, practices, or sympathies in the twentieth century is long. They included missiologists C. Peter Wagner and Paul Hiebert and humanitarian Bob Pierce of World Vision. Pastor and speaker Chuck Swindoll wrote a pamphlet entitled “Demonism” in which he confessed that after years of skepticism, he was “now convinced” that a Christian could be possessed. Christianity Today editor Harold Lindsell, who had experiences that reminded him of the Book of Acts, explained that he now believed that “New Testament power is available to Christians today.” In the early 1980s, Campus Crusade for Christ formally lifted its ban on tongues-speaking by staffers.

The list of American evangelicals who moved toward more supernatural discourse, practices, or sympathies in the twentieth century is long. They included missiologists C. Peter Wagner and Paul Hiebert and humanitarian Bob Pierce of World Vision. Pastor and speaker Chuck Swindoll wrote a pamphlet entitled “Demonism” in which he confessed that after years of skepticism, he was “now convinced” that a Christian could be possessed. Christianity Today editor Harold Lindsell, who had experiences that reminded him of the Book of Acts, explained that he now believed that “New Testament power is available to Christians today.” In the early 1980s, Campus Crusade for Christ formally lifted its ban on tongues-speaking by staffers.

Billy Graham’s Angels: God’s Secret Agents (1975) sold millions of copies, and the mid-twentieth-century American discovery of C.S. Lewis led to millions reading Miracles (1947) and Screwtape Letters (1943), which featured a senior demon instructing his demon nephew on how to corrupt human souls. Many of the most compelling accounts came from outside the United States. Bob Pierce’s film A Cry in the Night (1958), for example, featured what it said was “an actual view of demon possession” on the island of Bali.

In the enormously popular book The Cross and the Switchblade (1962), Nicky Cruz, a converted gangster, described his Puerto Rican childhood as the son of a satanic priest and priestess. “Satan must be unmasked,” Cruz explained. “He is not a harmless caricature or a myth left over from humanity’s primitive past.” In numerous books and countless speaking engagements, Cruz fired salvos at a rationalistic church culture increasingly “ignorant” and “apathetic” toward Satan’s threats. He and many others dominated a new wave of charismatic programming on radio and television in the 1980s.

The supernatural turn shaped even progressive evangelicals, many of whom had previously viewed Pentecostalism as an opiate that distracted adherents from addressing social inequalities. In a fascinating synthesis of supernaturalism and leftist critiques of technocratic liberalism, theologian Walter Wink spoke of expelling demons and principalities from political, economic, and cultural structures.

The enchantment of the Global South, in contrast to the West’s arid rationalism, appeared strikingly hopeful to evangelical boosters. A vast literature of miracle narratives, suggesting that God was dramatically working salvation abroad, circulated in the United States. This, combined with the postcolonial mood of the late twentieth century, suggested that Americans had much to learn from wonder-working Latin Americans.

If, as one Latin American theologian observed, “Liberation theology opted for the poor and the poor opted for Pentecostalism,” then perhaps spiritual warfare could save North America too. As conservative Protestants in the United States bemoaned what they perceived as pervasive secularism, dropping church attendance, and other pressing problems of modernity, new attention to angels and demons re-enchanted the West.

If, as one Latin American theologian observed, “Liberation theology opted for the poor and the poor opted for Pentecostalism,” then perhaps spiritual warfare could save North America too. As conservative Protestants in the United States bemoaned what they perceived as pervasive secularism, dropping church attendance, and other pressing problems of modernity, new attention to angels and demons re-enchanted the West.

In his article, Ashby, a pastor from a religious tradition not known for its Pentecostal vibe, maintains that immaterial realms matter even in the most mundane material realms of home living. Citing Paul’s letter to the Ephesians—“Our struggle is not against flesh and blood, but against the rulers, against the authorities, against the powers of this dark world and against the spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly realms”—Ashby exhorts husbands and wives to “suit up for spiritual war.” I don’t know that this exhortation happens without missionaries describing their experiences in the Majority World.