More than a third of this blog’s traffic this month has consisted of people reading a post on Christian responses to the influenza pandemic of 1918, when churches across the country closed for weeks at a time. Thousands more have come here to learn about the historical context for Martin Luther’s response to an outbreak of plague in 1527.

All that traffic points to one of the many reasons that historical study is so important right now, as people around the world cope with the spread of a novel coronavirus. As John Fea wrote last week, history can “put this pandemic in a larger context.” At his own blog, John has recounted multiple examples of Christian responses to the influenza pandemic of 1918, from the white evangelist Billy Sunday to the black Presbyterian pastor Francis Grimké. Other historians have written about Christian responses to earlier epidemics, from the Black Death of the mid-14th century to infectious diseases afflicting the Roman Empire. Tomorrow at noon Philip will be leading a free webinar for Baylor on this very topic.

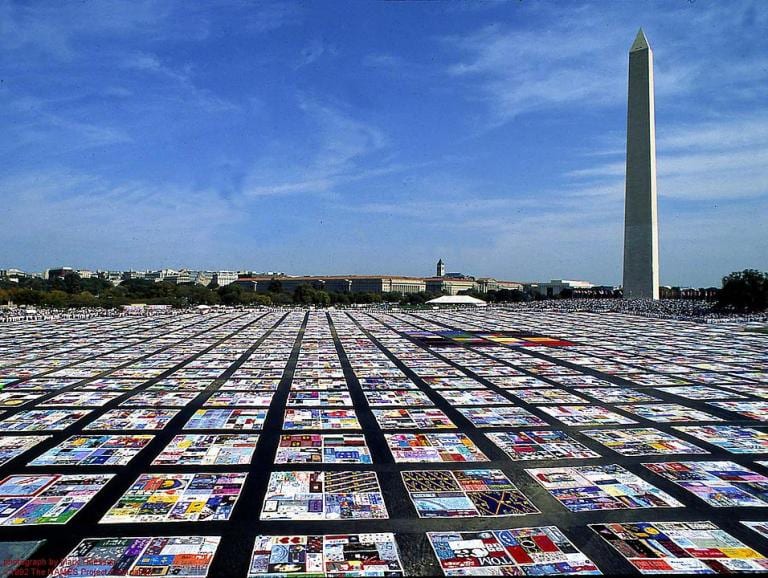

Why is all this so helpful? John suggested that historians might “alert us to potential present-day behavior by reminding us of what happened in an earlier era.” (That was certainly my goal in blogging about the 1918 flu, when Christians offered the same range of responses to the loss of public worship that we’ve seen this month: from creative adaptation to grudging acceptance to angry defiance.) While that kind of history can inspire us, as when I read of the 2,000 Catholic nuns who cared for influenza patients in hard-hit Philadelphia, it can also warn us of the limits of human compassion. Over the weekend, I was saddened to read historian Jim Downs’ reflection on two epidemics that revealed darker sides of American history: an 1860s outbreak of smallpox and the AIDS epidemic of the 1980s, tragic cases in which the government allowed disease to ravage minority groups (African Americans and gay men, respectively).

I’ve probably reached the limits of my ability to write meaningfully about the history of pandemics, but I hope that more knowledgeable historians will continue to share their expertise with an anxious, confused public. Studying pandemics past can help us respond to the present crisis more soberly: nearly blithe nor fearful, but able to take a longer view of events whose causes are complicated but knowable, and whose consequences are serious but difficult to predict.

Meanwhile, I plan to turn back to other topics, as I’m sure my colleagues here at The Anxious Bench will do. But even as we write about histories seeming to have nothing to do with disease, I think we can provide important service in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic.

First, we can provide distraction. With more people given more time to read, historians have a chance to feed different interests and to stimulate a wider curiosity about the past. As much as history promises to help us understand our response to COVID-19, it should also divert us from paying all of our attention to that disease.

For if C.S. Lewis was right that learning of all kinds should continue in wartime, so it should in the midst of a public health (and economic) crisis. “If you attempted,” he warned in a 1939 sermon, “to suspend your whole intellectual and aesthetic activity, you would only succeed in substituting a worse cultural life for a better.” What Lewis said about war — even in a cause that is, “as human causes go, very righteous” — pertains to disease — even one as serious as COVID-19: it “will fail to absorb our whole attention because it is a finite object, and therefore intrinsically unfitted to support the whole attention of a human soul.”

So teaching, research, writing, and the other tasks of historians should and will continue. If I’m taking seriously what I wrote last week about being faithful to my particular, multiple callings, then I need to recognize that I still have a Charles Lindbergh biography to write and I still have classes to teach — albeit online — on everything from sports history to historical methods.

But in the process of doing the work of history, on any topic at any time, I also think John Fea is right that historians can help cultivate the habits and traits of citizenship. Like other humanities disciplines, he wrote, history “teach[es] students how to think critically about their world” — e.g., to evaluate information and its sources, be they scientists, journalists, political leaders, or social media connections. Moreover, John argues that history helps prepare citizens possessing “the virtues necessary for a thriving democracy,” virtues like “empathy, humility, and selflessness.”

Yes, and amen. Perhaps history can continue to be the “engine of empathy” that I called it two years ago, in a post suggesting five reasons why Christians should study history:

…at a time when political, cultural, intellectual, demographic, and technological forces are segregating like-minded from like-minded, thinking historically expands the very definition of neighbor, so that it spans time as well as space. History teaches us to listen to those we might want to dismiss as enemies, to remember that those eyewitnesses to the past were fellow human beings whose vanished lives leave behind traces of the divine image they bore. For long moments, history even strands us in “a foreign country” and lets us feel what it’s like to be aliens and strangers.

If we needed historical empathy in March 2017, we need it all the more in March 2020. At a time when even our view of the coronavirus reflects political polarization, when our social fabric risks fraying even faster than it already was, when we’re physically separated from most other people — and forced into prolonged proximity with a few others… I pray that historians can help us learn to love our neighbors well.