As David hinted in his post last week, the history of American missionaries is closely linked with the projection of American power in lands far removed from the United States. But in the 19th century, the missions field included most of this country itself, as Christian groups contended for the souls of both indigenous persons and white settlers on the frontier. I’ve had to learn a bit more of that history in the process of writing the initial chapters of my spiritual biography of Charles A. Lindbergh, whose grandfather had significant encounters with at least two such “home missionaries.”

Well into the history of the United States, the frontier ran straight through Minnesota, which entered the Union three years before the Civil War. French Canadian clergy had visited the area since the 17th century, but Catholic missions achieved more permanent gains in the mid-19th century, when a Slovenian priest named Francis Xavier Pierz was assigned to the northern half of the Minnesota Territory. (“A missioner in America,” he explained to a priest back in Europe, “is like a plaything in the hand of God.”) While he made few converts among the Ojibwe, Pierz succeeded in recruiting Catholic immigrants from central Europe — and then in securing the help of monastic orders, including the Benedictine monks and nuns who founded what are now Saint John’s University and the College of Saint Benedict. One St. John’s teacher established his own academy in the late 1870s; its students included Charles A. Lindbergh, Sr., who went on to start a law practice in nearby Little Falls — where Franciscan nuns founded a hospital and orphanage.

Unwilling to cede any part of the United States either to Roman Catholicism or the religions of the native inhabitants, Protestant missionaries arrived in the same part of Minnesota about the same time as Father Pierz. In 1849, missionaries Frederick and Elizabeth Ayer relocated to Belle Prairie and founded a school that educated native, white, and mixed race children. By the end of that decade, the Ayers’ mission had spun off a group that founded the First Congregational Church of Little Falls, where Charles Lindbergh occasionally (and unhappily) attended worship services as a child.

Not far away, a Congregational pastor named Charles S. Harrison arrived in Sauk Centre in 1860. More famous as the home town of Sinclair Lewis — and the inspiration for his novel Main Street — Sauk Centre was little more than a village when Harrison was sent there for two years by the American Home Missionary Society (AMHS). Before moving on to a new missions field, Harrison wrote an article for the society about a remarkable incident the year before at Sauk Centre’s mill.

One summer day in 1861, a Swedish immigrant arrived to saw timber for the expansion of his growing family’s farm house in nearby Melrose. But in a freak accident, the saw blade cut so deeply into the left side of the Swede’s body that witnesses saw his heart beating. The victim’s name was August Lindbergh, grandfather of Charles.

[While I’m at it, let me share a digital map I’m working on, showing a variety of sites related to the spiritual biography of Charles Lindbergh and his family. I’m still adding to the map, but what’s already there for Minnesota will give you a clearer sense of this post’s geography.]

Just two years in the United States, he was in dire shape when Rev. Harrison arrived on the scene. While they waited for the nearest doctor to make the long journey from St. Cloud, Harrison talked to August Lindbergh through a translator. Here’s how the missionary told the story to readers back east:

We feared he would die before the surgeon came, and I was anxious to do something for his soul. I could not talk fluently with him myself, so I rode in haste, eight miles, for a good Scandinavian brother who labored with him faithfully all night, and in the morning the stern fortitude of this strong man softened into the calm serenity of the Christian’s hope. It was a sublime spectacle—a great man lying on his lowly couch. He had no tears for his own bitter anguish; he wept not at the agony of his loved companion; but when the love of God flooded his soul, with streaming eyes and touching eloquence he spoke, in broken language, of his new found joys. It was the most eloquent sermon I ever heard. His neighbors were assembled, and there was hardly one who did not weep with him. At length, after over thirty hours’ waiting, the surgeon came; his arm was amputated, and he lives, praising God’s mercy in afflicting him, and quoting that passage which speaks of “entering into life maimed” [Matt 18:8]. It was indeed a wonderful providence, sent on purpose for his soul’s salvation.

Did Charles Lindbergh’s grandfather really experience something like a near-death conversion? Rev. Harrison may have felt tempted to embellish the story, to reassure the AHMS’ Eastern backers that the spiritual fields of the West were indeed ripe for harvest. Not long before that accident, he had apologized in the same journal for not raising more funds ($1.50 for his first year in Sauk Centre), explaining that the people in that part of Minnesota “are poor, and there are but few of them professors of religion.”

Such missionaries, wrote church historian Charles Thrift in 1937, “were not exempt from the hardships and privations of the frontier. Indeed the very nature of their tasks often made them feel the harshness of their environment even more keenly than did the average settler.” Hardship and privation show up again and again in the pages of The Home Missionary. Harrison came to Minnesota “at great personal sacrifice,” another AHMS worker reported in 1861, after finding that the missionary, his wife, and infant child lived in a one-room house measuring less than 200 square feet. “I believe that not one of these places, in their present circumstances, could possibly give their missionaries a living, without your aid,” that correspondent concluded. “All these brethren are doing a blessed work; and most disastrous must it be to these communities, if the Society should be so crippled as to be obliged to withhold its appropriations… May God avert them from such a disaster.”

It wasn’t just evangelical groups that sent Protestant missionaries to Minnesota. After being installed as Minnesota’s first Episcopal bishop in 1859, Henry Whipple dispatched priests across the state to found new churches. In the diocese’s 50th anniversary history, George Clinton Tanner paid tribute to pioneering clergy like “that indefatigable missionary” George Stewart, who “ministered in prairie school houses and in logging camps.” (The latter later to be the setting of a different kind of missions project.)

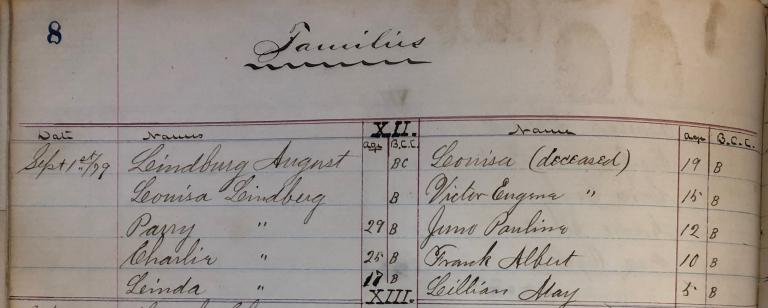

Writing in 1909, Tanner had to admit that the work of home missionaries rarely bore long-lasting fruit: “While only three parishes of that day have become strong centers of church work in all this field… this could not be foreseen. The pioneer missionaries of the Church in Minnesota sowed the good seed beside all waters.” One of the parishes that didn’t last was Trinity Mission Church of Melrose, where Stewart served as priest in the 1880s. Formally organized in September 1879, its parish record book lists a handful of founding families. Only one has a (misspelled) Scandinavian name: