This Monday, the Clemson Tigers face off against the LSU Tigers in the College Football Playoff National Championship. For Dabo Swinney, Clemson’s coach, the game will not only be a contest of athletic skill, but also a testimony to religious faith. Under Swinney’s leadership, the Clemson Tigers have earned a formidable record—they are the defending champions, and Monday’s game will be their third appearance in the championship matchup in four years. But Swinney is famous not simply for leading his team to victory, but for doing so while putting his evangelical Christian faith front and center. In Swinney’s view, the team’s triumphs owe to talent, teamwork, and, above all, trust in God. Swinney made this conviction clear when Clemson captured the national title last year. “All the credit, all the glory, goes to the good Lord,” he proclaimed.

In the United States, the overlap of football and faith has long drawn the fascination of both the press and the broader public, especially in the case of Clemson’s football team, which has been both uncommonly successful and unabashedly Christian. A look at how the team is represented in news media reveals an enduring narrative: that Clemson’s football team is not only religious, but successful because they are religious. Indeed, as recent research shows, this narrative is part of a broader trend in American sports journalism that correlates religious faith with good character and athletic excellence. But such a favorable view of athletes’ religiosity is by no means universal. Elsewhere in the world, sports writers do not link religious faith with athletic or personal excellence and are, in fact, quite skeptical of athletes’ open displays of faith, if they choose to cover it at all.

Religious Athletes as Men of Good Character

In “Cross Cultural Comparisons of Religion as ‘Character’: Football and Soccer in the United States and Germany,” a paper recently published in The International Review for the Sociology of Sport, Michael Butterworth of Ohio University and Karsten Senkbeil of the University of Hildesheim argued that news media in the United States tend to portray the Christian faith of football players in a positive light. American sportswriters equate Christian faith with success in several ways. First, they connect religious faith—in particular, Christian faith—with both personal virtue and athletic achievement. They suggest that devout Christian faith helps coaches and players to be strong leaders. Finally, they portray a shared Christian faith as foundational to team cohesion. As Butterworth and Senkbeil wrote,

When it comes to athletic achievements, the American master narrative usually suggests that religious commitment translates into extra commitment and willpower on the field as well, and thus ultimately to a higher level of athletic performance under pressure,” wrote “Also, a team’s solidarity, determination, and self-reliance are enhanced by communal prayers, so religion is in fact a positive factor in athletic success.

A look at news media coverage of the Clemson Tigers football team confirms the findings of Butterworth and Senkbeil. In magazine and newspaper articles, journalists have regularly highlighted the team’s distinctive Christian culture, often presenting it as central to its success.

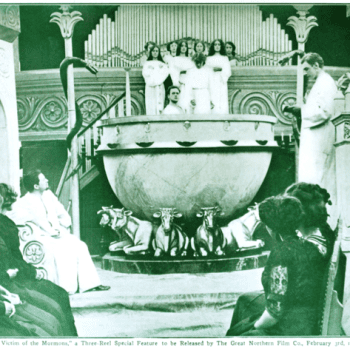

Consider, for example, how American sportswriters portray Swinney. To be sure, Swinney’s open emphasis on Christianity has drawn criticism and legal action, especially after one of his players was literally baptized on the football field. Nonetheless, Swinney has enjoyed favorable depiction in the news media as a devout evangelical Christian who is capable of leading and recruiting an excellent team because of his Christianity. For example, in “How Dabo Swinney’s Christian Evangelism Boosts Clemson Recruiting,” Joshua Needelman at the Charleston Post and Courier described how thirteen current and incoming players committed to Clemson because they were drawn to Swinney’s faith-centered approach to football. According to Needelman, Swinney’s Christian leadership and Clemson’s religious culture “struck a chord with prospects who come from strong Christian backgrounds.” Because success during the football season depends so much on success during the recruiting process, Needelman suggested that Christianity itself is Swinney’s winning strategy. Similarly, in the article “Faith, Football, and the Fervent Religious Culture at Dabo Swinney’s Clemson,” Tim Rohan at Sports Illustrated tied Swinney’s coaching triumphs to his emphasis on religion:

…Swinney has built Clemson into a one of the premier college football programs in the country, while keeping religion front and center. Swinney has hired a team of Christian coaches and support staffers; he’s used faith as a selling point for recruits; and he’s created an environment where players openly discuss and bond together over their Christianity. Steeped in religion, Clemson has won two of the last three national championships, and is ranked No. 1 again this season.

Put simply, both Rohan and Needelman portrayed Christianity not as as incidental to the Clemson Tigers’ triumphs, but as intentionally central to it, in large part due to Swinney’s Christian leadership.

At the same time, news media portrayals of Trevor Lawrence, Clemson’s star quarterback, illustrate how American sports journalists tend to present Christianity as a positive influence on athletes’ lives and as evidence of good character and virtue. According to media accounts, Lawrence had troubled beginnings but experienced a religious awakening that transformed both his faith and his football career—in other words, a classic conversion story, but this occurring in the world of elite college sports.

A September 2019 Sports Illustrated profile of Lawrence followed the familiar narrative arc of an old-time gospel hymn. “[Lawrence] was lost,” wrote the author, Ross Dellenger. “Not physically lost, but he was spiritually lost, emotionally lost.” Describing him as “deeply troubled,” Dellenger included a quote Lawrence, who offered a tantalizingly vague account of his life during his turbulent first year in college. “Being in college,” Lawrence said, “I made some decisions… first year being on my own, got this freedom now… I made some decisions, not good decisions.”

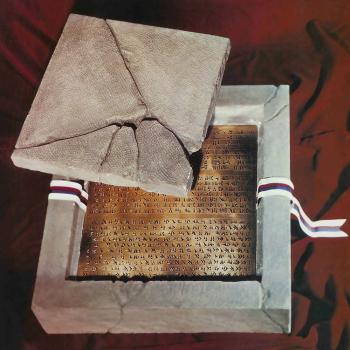

According to the article, though, Lawrence found success at Clemson because he found salvation, thanks to NewSpring Church, a South Carolina church that plans a weeklong religious retreat called The Gauntlet. As Lawrence told Sports Illustrated, the retreat was when he “was truly saved.” “I already believed there was a God, that was real,” Lawrence said. “I never had experienced it myself. Having them kind of as a guide and seeing things and getting advice… it was me seeing that this stuff was real. I could tell.”

As Dellenger wrote, faith became “an outlet to escape from the chaos” for Lawrence, who proudly shows his faith to the broader public:

Lawrence is not shy about discussing his faith. In fact, he wears it. On his wrists are a half-dozen personalized rubber bracelets, each a different color with its own message. There is one representing a church band, two more portraying Bible verses and another recognizing Clemson’s 2018 national championship.

Dellenger’s profile of Lawrence concluded not simply with the act of redemption, but with the possibility that Lawrence’s conversion and Christian conviction might change the lives of those around him. Dellenger described how Lawrence, who once was lost but now was found, shares his faith in a way that he hopes will inspire others:

It’s hot, it’s sweaty, but it doesn’t matter, because Trevor Lawrence is found. “I don’t think anyone has abilities for no reason,” Lawrence says. “I don’t think anything is coincidence. God gave me these things for a reason, not just talent on the field, but other opportunities to be a light to people.”

According to media accounts, the religiosity of Clemson’s team is not limited to Swinney and Lawrence, but defines the entire team. Lawrence leads a team that is depicted in the press as not only unabashedly religious, but as unusually close and affectionate—another way that the news media positively portrays Clemson’s Christian culture. As Gene Sapakoff wrote at the Charleston Post and Courier, “‘love’ is at the core of Clemson’s four national championship game appearances in five years.” Sapakoff described how team members regularly text “I love you” to one another and are united by strong bonds of care. In his story, Sapakoff did not discuss religion directly. However, his portrayal of the team’s culture reinforced Clemson’s popular image as distinctively virtuous, and it dovetailed with Butterworth and Senkbeil’s observation that American news media present religious piety as linked to good moral character, team solidarity, and athletic success.

Religious Athletes as “Remote-Controlled” Dolls

But how do news media portray the relationship between sports and religion in other countries and cultural contexts? Butterworth and Senkbeil argued that Americans’ tendency to equate Christian piety with athletic and personal excellence is not universal, and they presented the case of German news coverage of soccer to illustrate this point. Germany, like the United States, is characterized by a meritocratic sports culture and a majority Christian population. However, unlike their American counterparts, German sports journalists handle the religiosity of elite athletes very differently.

Butterworth and Senkbeil found that in Germany, sportswriters discuss the religious faith of athletes only rarely. European soccer organizations, they pointed out, do not involve themselves with religious organizations, and when they engage in social issues, they emphasize non-religious issues such as opposition to racism and environmental sustainability.

Even when an athletic event involves unambiguously religious figures and messages, the German news media describes the event in terms of secular values. For example, after the suicide death of Robert Enke, a goalkeeper for the German national team and a practicing Catholic, a Catholic priest led a prayer and offered a message about God’s grace to an arena full of grieving fans. However, none of the mainstream German media mentioned the religious figure or message at all and emphasized, instead, secular concerns such as mental health.

On the rare occasion that German sportswriters do talk about religion, they tend to be skeptical of overtly religious athletes. Religious figures in the German media have been described as “remote-controlled” (in the words of one publication) by money-hungry, corrupt churches. As Butterworth and Senkbeil wrote, German sportswriters “overtly belittle these players, implying that they, simply put, are too ignorant to fully understand what they are doing when they show their Jesus slogans.”

In sum, Butterworth and Senkbeil found that the German news media do not frame the religious faith of athletes as essentially positive, as American news media do, and German sports journalists do not see religious faith as essential to good character, leadership, community building, and athletic success. “German media imply no causality whatsoever between an athlete’s religiousness and his athletic success, neither positive nor negative,” they wrote.

Why do German news media—and German people in general—think about the relationship between faith and football differently from Americans? The researchers offered several explanations. First, religious diversity might play a role. The largest German stadiums are located in large, multicultural cities, with significant Muslim populations, and young, working-class, Muslim men comprise some of their most committed fans. Highlighting the Christianity of some players risks alienating this important fanbase. Moreover, German soccer is centered on a “youth culture” that rebels against messages that are “patronizing, moralistic, and condescending.” Finally, Germans tend to see religious faith as a private matter, rather than something that should be on public display.

Butterworth and Senkbeil’s research reveals very different media narratives and religious cultures, and it raises more questions for consideration. One wonders if, as the American population becomes more religiously diverse—including religiously unaffiliated—the overlap of faith and football, along with the news media celebration of it, will decline. Alternatively, and perhaps more likely, Americans’ existing assumptions about faith, character, and athletic excellence will be applied to religiously devout non-Christians, whose piety might be portrayed by sportswriters as essential to success. Will sports become yet another space where minorities need to claim a religion (and do so loudly) in order to be respected and appreciated in America?

Finally, sports could continue to be yet another arena in which American society becomes increasingly polarized. Evangelical Christianity remains so tightly linked to American football, but one wonders if non-evangelical groups will ever forcefully counter the status quo. Dabo Swinney, among all the praise, has no doubt been the target of criticism, but it is also hard to imagine anybody taking his job away as long as he is winning. Perhaps more than they love religion, Americans love winners—a lesson we have witnessed in politics, for sure, and also in sports.