“We seem,” said our guest preacher on Christ the King Sunday, to think “we have immunity from learning anything in history.” I don’t think she meant that Americans are disinterested in the past, but that we tend to look backwards in search of reassurance and validation — not challenges to our assumptions. As her sermon concluded a series on the kings of the Old Testament, I thought about the selective, convenient way that many of us peruse the history section in the library that is the Bible.

Consider, for example, how evangelical Christians who back Donald Trump like to liken the president to leaders from biblical history. To justify their support for a man of abundant iniquity and dubious piety, they compare Trump to the Persian ruler Cyrus, who conquered the Babylonian Empire and allowed Jewish exiles to return to Jerusalem. As Tara Isabella Burton explained last year:

For believers who subscribe to this account, Cyrus is a perfect historical antecedent to explain Trump’s presidency: a nonbeliever who nevertheless served as a vessel for divine interest.

For these leaders, the biblical account of Cyrus allows them to develop a “vessel theology” around Donald Trump, one that allows them to reconcile his personal history of womanizing and alleged sexual assault with what they see as his divinely ordained purpose to restore a Christian America.

Problematic as that analogy is, it’s not just Cyrus. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo has compared Trump with Esther, the Jewish queen of a later Persian monarch. Then last month outgoing energy secretary Rick Perry, another evangelical in the Cabinet, told Fox News that:

God uses imperfect people through history. King David wasn’t perfect. Saul wasn’t perfect. Solomon wasn’t perfect. And I actually gave the president a one-pager on those Old Testament kings about a month ago. And I shared it with him and I said, “Mr. President, I know there are people who say that you say you were the chosen one.” And said, “You were.” I said, “If you are a believing Christian, you understand God’s plan for the people who rule and judge over us on this planet in our government.”

I’ll leave it to historian John Fea to explain why Christian belief in God’s sovereignty doesn’t lead to Perry’s “chosen one” conclusion, and let historian Neil J. Young explain why “self-rationalization for voting for Trump… has given way to a sort of self-absolution for continuing to support him in light of his myriad imperfections in office, not least his debased character and rampant illegalities.” But Perry’s broader mention of “Old Testament kings” made me think back over those sermons our congregation has heard recently from the books of 1st & 2nd Kings.

Growing up, those were some of my favorite scriptures. While I know now that they’re not histories in the modern sense, they helped kindle my lifelong interest in the politics and religion of the past. And as a Christian who finds the Trump-as-Cyrus (let alone David) argument utterly unconvincing, I recognize that I’m still tempted to look to the political histories of the Old Testament for typologies that help explain events in my own time.

As our guest preacher took us through 2 Kings 22-23, for example, I felt my mind start to cast about for a contemporary American leader who matches the type of King Josiah. The last king of Judah who “did what was right in the sight of the Lord, and walked in all the way of his father David” (22:2), Josiah led a religious reformation, restoring the temple and calling his people back to monotheism when the high priest Hilkiah rediscovered “the book of the law” (likely Deuteronomy). As impressively, our guest preacher pointed out, Josiah acknowledged his own responsibility, ripping his garments when he realized that the people of God had neglected the word of God.

It’s easy to see how Christians across the political spectrum could adapt this story to their own partisan purposes, lamenting 21st century American versions of the various idolatries pervasive in Judah and celebrating a rising young leader of integrity and resolve who would help call Americans back to the path of truth and righteousness. Precisely because that analogy comes so easily, I’m trying to bear in mind the warning of Cambridge University scholars Judd Birdsall and Matthew Rowley:

To avoid the weaponizing of Scripture and the sacralizing of politics, we urge our fellow Christians to refrain from using biblical typologies in political life….

The problem with biblical typologies comes when we try to link them to the political leaders and causes of our day. Whereas New Testament typologies pointed to spiritual claims about Christ and his church and carried for Christians the authority of divine inspiration, typologies of the Trump-as-Esther sort serve partisan agendas and rely on subjective interpretation.

After all, the Bible “contains a vast array of possible biblical types that one can cherry-pick to legitimate just about any political leader or partisan agenda.”

But if we should beware self-serving historical analogies or typologies, we shouldn’t then decide that the royal stories of the Hebrew Bible have nothing to teach citizens of a democratic republic. The contexts of Josiah’s court and our system of government are vastly different, but Old Testament commentator Rebecca Kruger Gaudino still urges us to study this past with an eye to the present: (quoting here from her introduction to 1st Kings in the Renovaré Spiritual Formation Bible)

To read 1 & 2 Kings today is to be invited into an unsettling reflection on Israel’s public life—and on our public life. The theologians of 1 & 2 Kings insist that public life can and must be aligned with the law of God, and they mourn and rage that public life is, instead, the very place of routine compromise. To read 1 & 2 Kings is to see that all areas of public life—political, religious, economic, judicial, and military—and the lives of individuals caught up in this public life are open to God’s review and resolve. It is also to see that understanding God’s resolve for public life is an absolutely essential, and yet regularly perplexing, task.

…These biblical texts vehemently assert that there is a moral order in God’s creation, that God has a tenacious resolve about this world’s life—and that we resist this resolve at our peril.

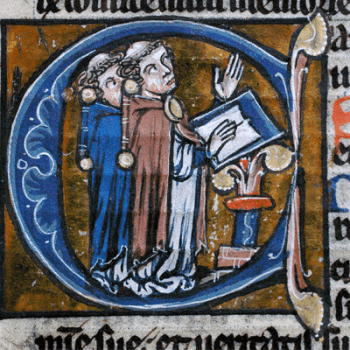

But instead of focusing our attention on the titular monarchs of 1st and 2nd Kings, Gaudino emphasizes the role played by another group: the prophets, whom “God mobilizes… to invade royal space and stand nose to nose with the king. Backed by the authority of the true Sovereign of Israel, the prophets look kings up and down and pronounce God’s word, in often searing language.”

And they do the same to us. As we read such texts, the prophets continue to “summon us to see the gods we and all our institutions and governments worship, often the very gods of 1 & 2 Kings: might, influence, wealth.”

So let’s go back to the story of Josiah, the rare king who gladly seeks out the oracle of God after learning that the law of God has been neglected. After the rediscovery of the Torah, he sends a delegation to a prophet, who gives them this message for the king:

“Thus says the Lord, the God of Israel: Tell the man who sent you to me, Thus says the Lord, I will indeed bring disaster on this place and on its inhabitants—all the words of the book that the king of Judah has read. Because they have abandoned me and have made offerings to other gods, so that they have provoked me to anger with all the work of their hands, therefore my wrath will be kindled against this place, and it will not be quenched. But as to the king of Judah, who sent you to inquire of the Lord, thus shall you say to him, Thus says the Lord, the God of Israel: Regarding the words that you have heard, because your heart was penitent, and you humbled yourself before the Lord, when you heard how I spoke against this place, and against its inhabitants, that they should become a desolation and a curse, and because you have torn your clothes and wept before me, I also have heard you, says the Lord. Therefore, I will gather you to your ancestors, and you shall be gathered to your grave in peace; your eyes shall not see all the disaster that I will bring on this place.” (2 Kgs 22:15-20)

In the end, Josiah goes to his grave in war, not peace, but he does avoid seeing the disasters that befall his less righteous sons and grandson.

The prophet reminds us here in the 21st century of the importance of humility in our leaders and should make us ask how we have abandoned God to worship our own idols. But as striking as the oracle itself is the identity of the person who speaks for God to the king. Here’s the verse I left out:

So the priest Hilkiah, Ahikam, Achbor, Shaphan, and Asaiah went to the prophetess Huldah the wife of Shallum son of Tikvah, son of Harhas, keeper of the wardrobe; she resided in Jerusalem in the Second Quarter, where they consulted her.

(See also the parallel passage in 2nd Chronicles.) Claiming to speak with the same authority as her contemporaries Jeremiah and Zephaniah, Huldah is one of five women in the Old Testament described as a prophet.

I don’t mean to identify a Huldah, Deborah, or Miriam already on the American religious scene. But if we’re going to learn any lesson from these biblical histories, it’s that time and energy spent legitimating those in power would be better spent listening for those who speak truth to power. If we dare to seek a historical type, let it be a Daniel, not a Cyrus; a Nathan, not a David; a Huldah, not a Josiah.

To do so, we likely will need to tune our ears to the voices of women like Huldah, and others drowned out by those who hold power in church and society. For if our contemporary prophets are anything like those Gaudino describes in 1st & 2nd Kings, they will be “figures of immense, God-given power” who “step out of… improbable places and from the ranks of… ‘no-account’ people to speak the truth about the kingdom.”