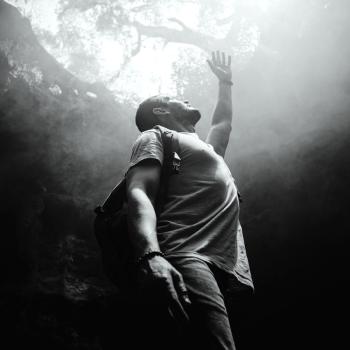

Pulitzer-prize winning writer Timothy Egan takes to the road as a pilgrim not because it is easy but because it is hard. His book,, A Pilgrimage to Eternity: From Canterbury to Rome in Search of Faith, admits the cluster of concerns that set him out on the path: his family’s mixed and painful experience with Roman Catholicism; personal intentions, including prayers for a sister-in-law’s cancer; desire to hear from Pope Francis. But perhaps most compelling is his hopeful searching for evidence that faith really is warranted, that God is and that humans can accountably credit something rather than nothing: “if there are a small number of hardened truths to be found on this trail, let the path reveal itself….We are spiritual beings. But for many of us, malnutrition of the soul is a plague of modern life.” Egan chooses to travel the Via Francigena, less popularized than the Spanish camino to Santiago but a venerable route from Canterbury to Rome. Marked by a jaunty cartoon of a pilgrim in cape with staff, the well-maintained V.F., as Egan nicknames it, was charted for posterity by Archbishop of Canterbury Sigeric in 990. Since then, millions of pilgrims have walked the road over centuries. The EU applied its stamp of approval in 1994, supporting efforts to mark the way and ever more heartily encouraging travelers, religious or not, to enjoy this treasure of European cultural heritage.

Egan is surprised as he walks. As such, he is doing exactly what pilgrims should do. He discovers things as he arrives in places, Laon, Rheims, Saint Bernard, Aosta, Pavia, Bolsena. Perhaps Americans should know European history well enough not to be surprised, to have at handy reference the order of religious wars, empire risings and dissolutions, state unifications, canonizations, revolutions of science and economics and industry. But we don’t. And, amenably, Egan takes readers on his journey of discovery in ways that should be recognizable to charitably disposed and curious American travelers of all kinds. It takes being in these places, stumbling upon the earth-shattering or life-changing event or edifice that we all but forgot, to understand that they were and why they matter. Egan is credible and serviceable in narrating his discoveries. We are glad he learns them and learn along with him.

The startling thing to him, though, is that while Americans may not readily recognize the indispensable milestones of the history that made us the way we are, Europeans don’t either. Not any more. From his start in England, Egan discovers “the kingdom is fast losing its belief in God. For the first time, more than half of all British say they have no religion at all. Some are looking for answers in the five-thousand-year-old Neolithic mystery of Newgrange in Ireland….Others are dogmatically atheist.” Egan’s interest is in what happens to the landscape of faith when faith has vanished, when, as he reports, blasé Frenchmen in a village where he seeks markers of a massacre of French Huguenots not only can’t direct him to the right place, but hardly recall why such an event would have happened in the first place.

The relevance of religious history for the present, indeed. Egan may discover, and Europe may boast, a religious amnesia that blooms in tolerance, wisdom, and diversity. But too often it doesn’t. What Egan sees in Calais persuades him that it doesn’t, where supporters of “French identity” vilify refugees seeking safety there but Secours Catholique, a church-affiliated agency, distributes aid.

So here is another boomerang: a religion [Roman Catholicism] whose leaders once called on followers to wage savage war against faraway cities held by people of a different religion now fights to feed and protect forsaken members of that same faith from those same faraway cities. It’s heartening, a selfless act. The handful of people who still work every day to keep Christian tradition alive in France—those who should be most threatened by loss of identity from outsiders of another religion—are practicing core tenets of what they preach. On this day in May, the great centuries-old sanctuary of Notre-Dame may be unwelcoming and lifeless, but don’t let it be said that the Catholic church has given up on Calais.

Egan learns as though for the first time the legacy of religious conflict in Europe’s past, and his disapproval is a thread throughout, from assessment of the Crusades through early modern conflict to the world wars of the twentieth century:

A larger question, then: How can you join a faith whose nation-state followers have spent most of their years killing others of that same creed? How can you believe in a savior whose message was peace and passive humility, when the professional promoters of that message were complicit in so much systematic horror?

Egan might profit from leisurely tutelage in just-war theory and theologies of pacifism. But like most readers, like most people, he has not that luxury. To his credit, Egan addresses these topics as a solidly educated and curious-minded layperson who wants to know. Egan encounters religious folk who seem compelling to him—Pope Francis perhaps above all—and also those who disappoint. Monastics are alternately forbidding, inspiring, or inscrutable. He respects doubt, honest seeking. From my vantage, he is hasty in his assessment of figures like Augustine. But he has littlest patience with confident disbelief.

But I have another motive to get moving in this sanctified pathway. For the enfeebled Church of England, the figure of Jesus is almost an afterthought; he is “sometimes compelling,” as the Anglican bishop of Buckingham recently put it. I’m looking for something stronger: a stiff shot of no-bullshit spirituality….I’m no longer comfortable with the squishy middle; it’s too easy.

I like the book, though I dissent from some of his judgments. What impresses me is Egan’s inquiring gaze, humane evaluation, and the admission of limits, not least those of his pilgrim feet, which are not beautiful. Egan addresses readers viewing the Via Francigena as from afar. I have the happy fortune of reading the book as I am about to walk a piece of the V.F. with a group of students from Gordon-in-Orvieto, a college program hosting predominantly Protestant students in study of art, faith, and history. In coming posts, I will report on our experience, in conversation with Egan’s report on his.