With good reason, pundits, journalists, and scholars like us have spilled buckets of virtual ink trying to explain white evangelical support for Donald Trump — to the point of rethinking the very term “evangelical.” If you continue to find such questions interesting, let me encourage you to read two recent articles in the Washington Post — Elizabeth Bruenig’s account of her trip to evangelical churches in Texas and Julie Zauzmer’s report from three battleground states — plus Angela Denker’s new book, Red State Christians. (I’ll have an interview with Denker at Anxious Bench next month.) But I wonder if we haven’t focused too much on one branch of the American Protestant tree.

What of the Baptist, Episcopalian, Lutheran, Methodist, Presbyterian, and other Christians collectively known as the “mainline”? Their long-declining numbers now lag behind those of evangelicals, Catholics, and “the nones,” but white mainline (or, if you prefer, “ecumenical”) Protestants still account for nearly 15% of the American population. And their politics are far more complicated than you may realize.

Right away, let me stress that I’m not a political scientist, nor a historian of mainline Protestantism. But both because I’m currently attending a mainline church and because people like me have tended to look past that particular intersection of religion and politics in order to zoom in on evangelicalism, I want to note some statistics and hazard some perhaps foolish explanations. If actual experts out there would like to write a guest post following up on this one, get in touch with me. Now, on with the show!

Consider the largest Protestant denomination in my part of the country: the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (ELCA). At its annual meeting earlier this month, the ELCA not only passed statements condemning patriarchy and white supremacy, but made national news for declaring itself a “sanctuary church body.” Hundreds of delegates joined Lutheran activists in marching a mile to the Milwaukee office of the federal office of Immigration and Customs Enforcement, where they held a prayer vigil and posted 9.5 theses on care for refugees and other immigrants. “We put the protest back in Protestant,” proclaimed some of the signs held by protestors. (And I don’t think they meant it like one of our blogging neighbors does.)

As religion reporter Emily McFarlan Miller had predicted, the 2019 ELCA assembly offered “a window into the issues important to many progressive Christians across the country.” But how many of the ELCA’s 3.5 million members are actually (politically) progressive?

Gathering under the theme "We are church," voting members of the 2019 Churchwide Assembly of the #ELCA made a number of key decisions to further the mission and ministry of this church.

Summary of #ELCAcwa actions: https://t.co/aMk2oy4kVj pic.twitter.com/mTqTJNsY0V

— ELCA Lutherans (@ELCA) August 15, 2019

Consider some of the numbers that political scientist Ryan Burge has been crunching from the Cooperative Congressional Election Study (CCES), which surveys over 64,000 Americans every two years. Not only do 49% of ELCA respondents in the 2018 CCES identify as Republican (vs. 42% as Democrats), but even more approve of Donald Trump: 52% of those Lutherans, 35% strongly. When Burge drilled down to look at religious behavior, he found that ELCA support for Trump was strongest among those who attended church most often and weakest among those who show up just once or twice a year.

I don’t want to make too much of this. Pro-Trump numbers among ELCA respondents are dwarfed by those for evangelical denominations. For example, about half of Southern Baptists, Nazarenes, and Assemblies of God Pentecostals strongly approve of Trump’s performance, as do the majority of the ELCA’s Missouri Synod cousins. (Here too, it’s the most faithfully religious who are most likely to identify with the political right in the Age of Trump.) Meanwhile, other mainline groups skew darker blue: e.g., 55% of Episcopal and UCC respondents strongly disapprove of Trump, and historically black members of the National Council of Churches like respondents from the African Methodist Episcopal Church (83% strongly disapprove) and AME Zion (91%) are even more unified in their feelings about this president.

But the ELCA rank and file is not alone in defying the conventional notion of the mainline having become the Democratic Party at prayer. The PCUSA isn’t nearly as red on Burge’s chart as the PCA or Orthodox Presbtyerians (the single most pro-Trump group in the set, with 70% strong approval), but 52% of Trump’s fellow (?) Presbyterians do approve of his performance. The United Methodist Church skews even more sharply to the right, with almost three in five continuing to back this president.

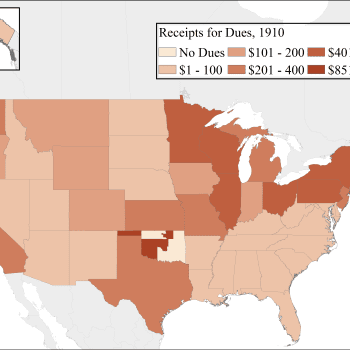

With Americans just over a year away from deciding on a second Trump term in office, these figures are not insignificant. The ELCA is particularly strong in Republican bastions like the Dakotas and Nebraska, but it also accounts for significant numbers of voters in three states that had tiny electoral margins in 2016: Pennsylvania and Wisconsin (two of the states Zauzmer visited) plus my own Minnesota. And each also has a good-sized UMC presence. (I’m relying on 2010 figures from the Religious Congregations and Membership Study for the adherence rates.)

- Minnesota (Clinton +1.5%): 139.1 ELCA per 1000 of population, 19.2 UMC

- Wisconsin (Trump +0.8%): 72.9 ELCA, 20.2 UMC

- Pennsylvania (Trump +0.7%): 46.6 UMC, 39.5 ELCA

In what’s bound to be a close 2020 decision, changing the opinion of these Christians could potentially alter the map of the Electoral College. Yet this far into the Trump administration, there continues to be a disconnect between denominations that loudly protest the most regressive aspects of the Trump presidency and their more politically complicated members.

There’s also a divide between clergy and laity. Consider a 2017 article by political scientists Eitan Hersh and Gabrielle Malina., who wondered just how partisan Christian pastors and their flocks were. Using earlier versions of the CCES survey and public data from the 29 states where voters register by political party, they found that clergy partisanship varies dramatically, if predictably, by denomination. Not only did nearly 100% of the ELCA’s seminary faculty register as Democrats, but so too did 73% of its pastors — vs. just 46% of the ELCA respondents in the CCES data, one of the biggest clergy-laity divides in the study.

They note how few religious Americans choose their congregation because of politics — not even 20%, according to a 2012 study — so it’s not necessarily surprising to see this kind of clergy/laity political split. (At one point in Red State Christians, Angela Denker writes about having supper with some Lutherans in Missouri. One young Trump backer glanced at an ELCA pastor in the group “and then looked away. ‘I don’t want my religion to influence my political beliefs,’ Eric said. ‘That makes it much more complicated.'”) Hersh and Malina still conclude that pastors have the ability to persuade differently-minded congregants on specific issues. But it wouldn’t surprise me if the pro-Trump rank-and-file in the mainline are just as likely as their evangelical counterparts to take more of their cues from Fox News and social media than from credentialed religious leaders speaking from more traditional pulpits.

Not that the evangelical/mainline distinction is as clean-cut as I’m making sound. There are no doubt lots of evangelicals sitting in Methodist, Presbyterian, and other mainline pews. And as I suggested here last fall, the fact that those churches are part of historically mainline denominations doesn’t keep them from participating in evangelical networks, supporting evangelical ministries, and using evangelical music and media.

All of which to say… mainline denominations are no more monolithic than evangelicalism. The ELCA resulted from a convoluted series of mergers that fused together Lutheran bodies of diverse theologies and pieties. I’m sure the same is true of the not-so-United Methodists, seemingly on the brink of a schism over sexuality and marriage. Here I’d also love to see someone like Burge break down the CCES data by location. He did find little difference between mainliners in the South vs. everywhere else, but I suspect that Lutherans, Methodists, and Presbyterians in rural areas, smaller cities, and exurbs would tend to have different politics than their urban and perhaps suburban co-religionists.

Or perhaps large numbers of white mainliners — and no American denomination is whiter than the ELCA — have simply been no more eager than their evangelical cousins to relinquish their historic influence over a country going through rapid social, economic, demographic, and cultural change. Maybe it’s not just evangelicals who can fall under the spell of Christian nationalism.

Or perhaps large numbers of white mainliners — and no American denomination is whiter than the ELCA — have simply been no more eager than their evangelical cousins to relinquish their historic influence over a country going through rapid social, economic, demographic, and cultural change. Maybe it’s not just evangelicals who can fall under the spell of Christian nationalism.

In her book, Angela Denker’s focus is on evangelicals, but I’d expect to find plenty of mainliners among the Red State Christians who “want to be the ones who get to define what America is, and for them, it must be conservative, and it must be Christian” — even if it takes a Donald Trump to keep it that way.