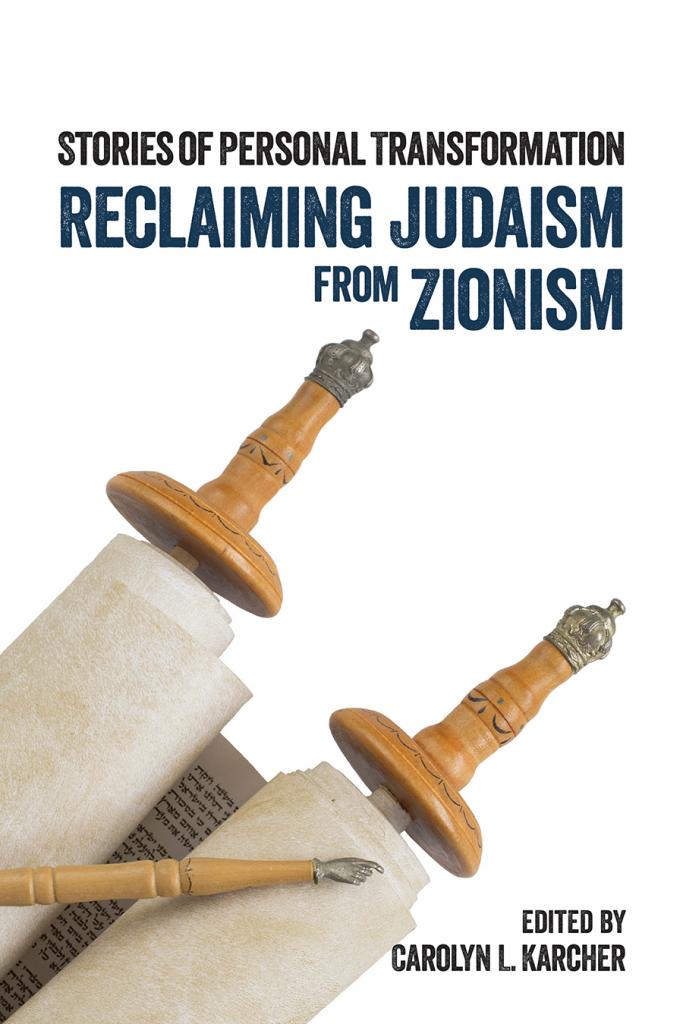

I’m pleased to welcome Carolyn L. Karcher to the Anxious Bench. Editor of the just-released Reclaiming Judaism from Zionism: Stories of Personal Transformation, Karcher is professor emerita of English, American studies, and women’s studies at Temple University, where she taught for 21 years. She is active in Jewish Voice for Peace and its DC Metro Chapter and is also associated with the New Synagogue Project. She is the author of Shadow over the Promised Land: Slavery, Race, and Violence in Melville’s America (1980); The First Woman in the Republic: A Cultural Biography of Lydia Maria Child (1994); and A Refugee from His Race: Albion W. Tourgée and His Fight against White Supremacy (2016).

***

David: Theodor Herzl was the “father of Zionism.” Who was he—and why did his vision resonate at the turn of the twentieth century?

Carolyn: Theodore Herzl (1860-1904) was a secular Viennese Jew whose pamphlet, The Jewish State (1896) is considered the “manifesto of the Zionist movement.” Herzl had moved to France, then regarded as the most enlightened country in Europe, and the one in which Jews were the most emancipated, to escape the recrudescence of antisemitism in his native Austria. Soon after his arrival, however, the Dreyfus case—the unjust conviction on flimsy evidence of a Jewish officer for treason—convulsed France; antisemitic riots erupted in nearly all of France’s cities and towns, as thousands filled the streets chanting “Down with the Jews.” Herzl concluded that antisemitism would never abate as long as Jews lived in Europe, and that their only recourse was to found a state of their own elsewhere. He initially cited Argentina and Uganda as suitable locations for a state that would serve as a refuge for Jews, but settled on Palestine because Russian Jews were already emigrating there in small numbers, and he realized that Palestine would prove more appealing to Jewish settlers. There were several reasons why Herzl’s ideas resonated at the turn of the twentieth century. First, this was the height of the imperialist era, when European nations were colonizing the Middle East, Asia, and Africa. Herzl naturally took his inspiration from imperialist ideology, presenting colonization as a beneficent enterprise. Second, he explicitly positioned the Jewish state he sought to found as an ally of the imperialist powers, “a rampart of Europe against Asia, an outpost of civilization as opposed to barbarism.” This argument would help convince the British to support a Jewish “homeland” in Palestine, as they did in issuing the Balfour Declaration in 1917, after Herzl’s death. Third, The Jewish State was truly a visionary work; it not only articulated the idea of a Jewish state, but provided detailed plans for establishing and developing such a state.

Rabbi Michael Davis writes, “Rabbinic Judaism is two thousand years old. Political Zionism is only 120 years old.” How does this historical argument help reclaim Judaism from Zionism?

Essentially, Rabbi Davis is refuting the common misconception that Zionism is part of Judaism. If political Zionism is only 120 years old, it obviously cannot be part of a religion that is two thousand years old. Historians have pointed out that the founders of Zionism were not religious Jews, yet these same founders used a very selective reading (and misreading) of biblical texts to justify their enterprise. Rabbi Davis is asking readers to return to the original religious principles that political Zionists have appropriated and in the process distorted.

You critique Zionists—not just conservatives, but also liberals such as Louis Brandeis and Felix Frankfurter—for being “blind” to the viewpoints of Palestinians. What were they not seeing?

You critique Zionists—not just conservatives, but also liberals such as Louis Brandeis and Felix Frankfurter—for being “blind” to the viewpoints of Palestinians. What were they not seeing?

As the historian John P. Judis points out, “Brandeis and his circle viewed the Zionist settlers as ‘pioneers,’ ‘pilgrims,’ and ‘puritans’ and the Arabs as ‘Indians.’” America’s seventeenth-century pilgrim and puritan settlers, of course, conducted wars of extermination against the Indians, and quoted biblical texts in justification of their bloody deeds. Later generations of pioneers continued these wars of extermination as they moved West, seizing the lands of other Indian tribes and forcing entire nations to relocate thousands of miles away, as in the Cherokee Trail of Tears. By idealizing the pilgrims, puritans, and pioneers, Brandeis and his circle were revealing their allegiance to the ideology of Manifest Destiny, which blinded them to the injustice of dispossessing the Indians. Of course, when they applied these categories to Jewish settlers and Palestinians, they exhibited the same blindness. For example, they advocated transferring the Palestinian population to other Arab countries, just as President Andrew Jackson and his supporters had advocated transporting the Cherokee from Georgia to Oklahoma. Similarly, Brandeis believed that Jewish settlers in Palestine were “trying to create a society based on democratic brotherhood,” but he did not realize that the exclusion and expulsion of Palestinians from this society made a mockery of its ideals of democratic brotherhood.

This volume contains dozens of personal narratives of Zionists who have moved toward solidarity with Palestinians and of Israelis striving to build an inclusive society. What are some of the common themes in these stories?

One of the common themes is shock, anger, and a sense of betrayal as those who visit occupied Palestine learn about the oppression to which Palestinians are subjected. “I kept asking myself how I could have gone so long without knowing any of this,” writes one contributor. “Was my upbringing one big lie that everyone else was in on? My teachers, family, camp counselors, family friends, my textbooks—did they all know? If so, why would they have lied to me, and how could I ever forgive them?” writes another. A second common theme is the recognition of a conflict between the progressive values that contributors have espoused in every other sphere of life, leading them to oppose the US wars in Vietnam and around the globe, and unquestioning support of Israel that Zionist ideology requires. A third common theme is the discovery that renouncing Zionism leads to the revitalization of both Jewish faith and Jewish identity. In the words of yet another contributor, “I have come to a place where Judaism—the texts, their ethical underpinnings, the idea of a cycle of holy time that separates holiness from the mundane—have come to be more meaningful to me than . . . when all religious practice seemed to pivot around Israel.” A fourth common theme is the embrace of solidarity instead of insularity, both as a response to antisemitism and as an assertion of Jewish identity. As Rabbi Brant Rosen puts it: “The new Diasporism seeks to recover the classically Jewish vision of a global peoplehood that discovers the presence of God anywhere throughout the world that our journeys may lead us. At the same time however, it rejects the narrow particularism of old; this new Jewish vision must inspire us toward solidarity, the building of bridges and the crossing of borders.” A fifth theme common to the narratives by Sephardi/Mizrahi, or non-European, Jews is the recognition that Israel has never been a haven for them. Most Ashkenazi (European) Jews are simply unaware of the extreme discrimination suffered by Sephardi/Mizrahi Jews in Israel and of the contempt with which their cultural heritage has been treated by the ruling Ashkenazi elite. These narratives shed new light on the racism that has pervaded Israeli society since its colonial origins (see question 3).

One of the contributors to the book, Rabbi Brant Rosen, says that Jews in Israel now “live in the most militarized state in the world, a garrison state that is becoming increasingly isolated from the international community.” Does this, ironically, represent a new kind of Jewish exile?

Rabbi Brant Rosen indeed asserts that the Jews who live in Israel are “experiencing a new form of exile”—that is, self-chosen exile from the world community. I would also call it a new form of ghettoization. A mantra that is continually repeated in Israel is “the whole world is against us.” The purpose of convincing the Israeli public that the whole world is against them is to induce them to believe that a garrison state offers their sole protection. At the same time, by flouting international law and institutionalizing human rights abuses, Israel is turning this mantra into a self-fulfilling prophecy that reinforces the perceived need for a garrison state.

Many of the contributors to this volume are Reformed Jews. How common is it for Orthodox Jews to reject Zionism?

Originally, of course, as my Introduction explains, and as Rabbi Michael Davis’s narrative confirms, both Reformed and Orthodox Jews rejected Zionism. Now the majority of both liberal (Reform, Reconstructionist, Jewish Renewal) and Orthodox sects uphold Zionism. Among the Ultra-Orthodox, however, the Neturei Karta still steadfastly condemn Zionism. Among other Orthodox groups, I know of a few people who reject Zionism. Many “observant” Jews (i.e., those who observe the kosher laws and the rules governing shabbat, regardless of whether they belong to Conservative, Reformed, Reconstructionist, or Jewish Renewal synagogues) also reject Zionism. A key factor seems to be the degree to which the teachings of the Jewish group in question emphasize ethical principles and interpret them as applying to all human beings.

Many readers of the Anxious Bench are evangelicals. There are still many Christian Zionists, but increasing numbers—including Gary Burge and attendees of the Christ at the Checkpoint Conferences at Bethlehem Bible College—express concerns about Zionism and would resonate with the message of this book. Do you see this movement growing or making a difference in American or Middle East politics?

You are in a better position than I am to judge whether the movement away from Zionism among evangelicals is growing. Certainly, if it does grow, it has enormous potential to make a difference in American Middle East policy. The Christian Zionist community is by far the largest and most militant pro-Israel constituency. In fact, Netanyahu has boasted that with the political and material support of Christian Zionists, he doesn’t need American Jews. Israel is definitely losing support among American Jews, especially young ones, who increasingly see a conflict between their liberal values and ethical principles and the policies of the Israeli state. If the same phenomenon were to occur among evangelicals, it would surely exert an impact on US policy toward Israel and eventually, perhaps, on Israeli policy.