“I have nothing to commend me to your consideration in the way of learning, nothing in the way of education, to entitle me to your attention; and you are aware that slavery is a very bad school for rearing teachers of morality and religion.” (Frederick Douglass, 1846)

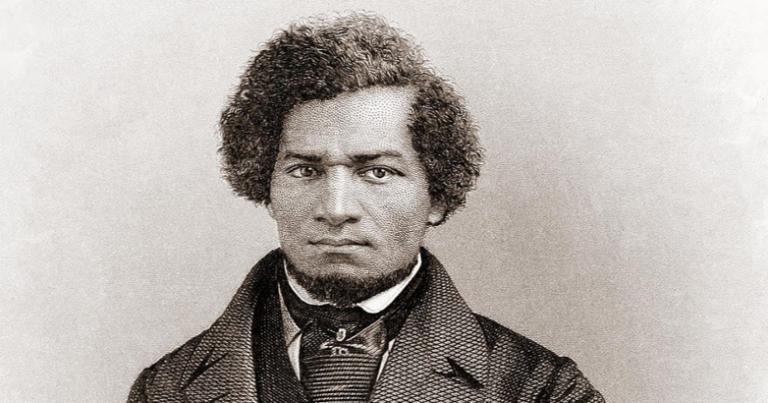

As a college professor, I know well the power of education mediated through teachers and institutions. But I’m also taken with the stories of self-taught learners, autodidacts as famous as the great abolitionist Frederick Douglass and as anonymous as Gust Peterson, a Wisconsin farmer whose father had emigrated from Sweden and whose great-grandson is writing this blog post.

In the last hundred years, famous autodidacts like Bill Gates and (yep) Charles Lindbergh have chosen to blaze their own educational trails, but in earlier eras, many people had no option other than to teach themselves. The United States’ vaunted system of public secondary education and impossibly vast array of postsecondary institutions were not accessible to most Americans until relatively recently. On the eve of World War II, the median American had completed fewer than nine years of school, a number that didn’t pass twelve until 1969. Even now, only about one in three Americans (age 25+) has a bachelor’s degree.

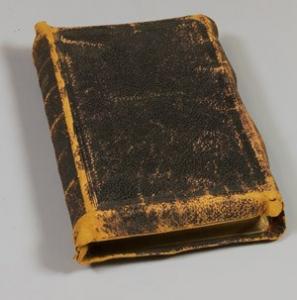

The Upper Midwest was a bastion of the high school movement at the turn of the 20th century, but recent immigrants like my Swedish ancestors had little choice but to prioritize work over education. (In the Peterson branch of my family tree, it was my mother’s generation that was the first to see consistent high school completion and the beginnings of college attendance.) Nevertheless, they were inveterate readers. After every hard day’s work on the farm, Gust Peterson spent time with the Bible (more on that soon) and books like Charles Morris’ Popular Compendium of Useful Information and Handy Dictionary of Common Things. A 1901 reference work that aimed to compile the most essential fields of knowledge for autodidacts, the compendium started with a preface insisting “that self-help is in all cases the best help, and home instruction often the best instruction… keep gathering knowledge or you will stagnate” (italics original).

That family history came to mind last month as I read David Blight’s biography of Frederick Douglass, whose ancestors had come to this country — and been kept from access to the education system — for very different reasons than my forebears. Douglass’ story illustrates how even self-directed education can lead to personal and social transformation, not just the acquisition of “useful information.”

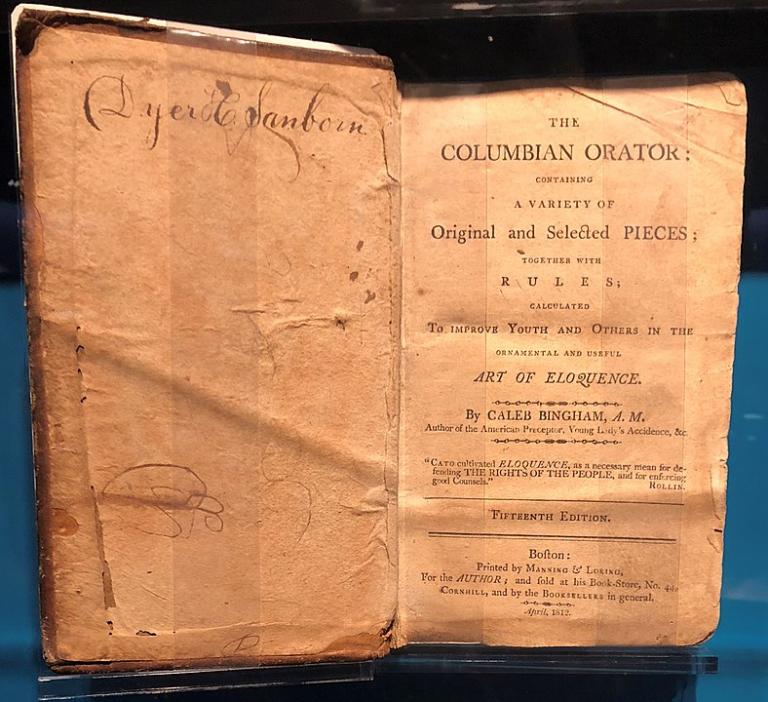

Born in 1818 as Frederick Bailey, he was sent to Baltimore at age 8, where Sophia Auld taught her young slave to read — to her later regret. By 1830 he had saved enough coins from odd jobs to buy a used copy of The Columbian Orator, the same reader that figured in Abraham Lincoln’s self-education. (Blight edited a bicentennial edition in 1998.) Compiled by Caleb Bingham, an anti-slavery teacher who was “determined to democratize education and instill in young people the heritage of the American Revolution, as well as the values of republicanism,” The Columbian Orator became Frederick’s “constant companion… almost his sole worldly possession when he escaped to freedom at age twenty.”

Recalling his plans to launch the North Star newspaper in the 1855 expansion of his memoir, Douglass remembered how many of his white friends were astonished at the notion of a “slave, brought up in the very depths of ignorance, assuming to instruct the highly civilized people of the north in the principles of liberty, justice, and humanity! The thing looked absurd. Nevertheless, I persevered. I felt that the want of education, great as it was, could be overcome by study, and that knowledge would come by experience….” In the preface to My Bondage and My Freedom, Dr. James McCune Smith — the first African American to complete medical school — lamented that “the force of their own education” kept most white abolitionists from appreciating “the highest qualities of [Douglass’] mind….”

From his public remembrances, it seems clear that Douglass was at once sensitive to the limitations of his learning, proud of his achievements as a self-taught man, and aware that his own educational story could help advance his war on slavery. Self-made men like himself, Douglass explained in an oft-repeated speech, are those “who, in a world of schools, academies, colleges and other institutions of learning, are often compelled by unfriendly circumstances to acquire their education elsewhere and, amidst unfavorable conditions, to hew out for themselves a way to success, and thus to become the architects of their own good fortunes.” But if he rejoiced that he was not among the “small class of very small men” for whom “the diploma is more than the man,” he bitterly recalled the particularly “unfriendly circumstances” that kept him “deficient in the polish and amiable proportions of the affluent and regularly educated man.”

“I have nothing to commend me to your consideration in the way of learning,” he told an English audience in 1846, “nothing in the way of education, to entitle me to your attention; and you are aware that slavery is a very bad school for rearing teachers of morality and religion… [The slave] is deprived of education. God has given him an intellect; the slaveholder declares it shall not be cultivated.” Douglass understood keenly that slavery and education could not coexist. He had started to develop the theme a year earlier in his first attempt at memoir, what remains the most compelling autobiography of an autodidact. “She was an apt woman,” he wrote of Sophia Auld, “and a little experience soon demonstrated, to her satisfaction, that education and slavery were incompatible with each other.” At first, Douglass recalled feeling that “learning to read had been a curse rather than a blessing. It had given me a view of my wretched condition, without the remedy. It opened my eyes to the horrible pit, but to no ladder upon which to get out.” But he soon came to see why slaveholders were so intent on denying him even literacy.

Lecturing on “The Nature of Slavery” in Rochester, New York in 1850, Douglass drew on his experience as an autodidact to explain why the “great mass of slaveholders look upon education among the slaves as utterly subversive of the slave system.

I well remember when my mistress first announced to my master that she had discovered that I could read. His face colored at once with surprise and chagrin. He said that “I was ruined, and my value as a slave destroyed; that a slave should know nothing but to obey his master; that to give a negro an inch would lead him to take an ell; that having learned how to read, I would soon want to know how to write; and that by-and-by I would be running away.” I think my audience will bear witness to the correctness of this philosophy, and to the literal fulfillment of this prophecy.

It is perfectly well understood at the south, that to educate a slave is to make him discontented with slavery, and to invest him with a power which shall open to him the treasures of freedom; and since the object of the slaveholder is to maintain complete authority over his slave, his constant vigilance is exercised to prevent everything which militates against, or endangers, the stability of his authority. Education being among the menacing influences, and, perhaps, the most dangerous, is, therefore, the most cautiously guarded against.

Nevertheless, The Columbian Reader came into his hands as a young man, and its prose, poetry, plays, and speeches started to give him “a vocabulary of liberation.” But Blight notes that it was “in a Baltimore church,” listening to white Methodist preachers, that a lonely, teenaged Frederick Bailey “may have encountered his first textual lessons in the natural-rights tradition, the philosophy that would give him a voice.” (Blight speculates that Douglass heard sermons on Galatians 3:28 — “…there is neither bond nor free… for ye are all one in Christ Jesus” — and perhaps 2 Corinthians 8:14 — “But by an equality, that now at this time your abundance may be a supply for their want, that their abundance also may be a supply for your want: that there may be equality.”) He had already heard Sophia Auld read aloud from the Book of Job, then an encounter with a black lay preacher commenced his lifelong reading and re-reading of the Old and New Testaments, in whose pages Douglass not only “cultivated his insatiable desire for knowledge” but learned to see “the world ‘in a new light” — to feel “new impulses for living, ‘new hopes and desires.’”

With the Scriptures as his core curriculum, Douglass absorbed the meaning of freedom from the letters of the apostle Paul and the stories of the Jewish people. (Heckled by racists in Boston in 1860, “Douglass answered from Exodus, ‘The freedom of all mankind was written on the heart by the finger of God!’”) Moreover, he used Scripture to teach himself the cadences of the prophetic voice. Blight observes that Douglass’ world-changing oratory remained “deeply indebted, consciously or not, to his life of reading and using the King James Bible.”

I hesitate to draw any especially close analogy between the situation of any 21st century American and that of 19th century Americans brutalized by slavery. But reading Blight’s biography of Douglass made me wonder if those of us who are part of the education system don’t perhaps underestimate the power of what we do. I came away all the more eager to discontent students with the figurative (hopefully never again literal) bondages of ignorance and offer them instead intellectual “treasures of freedom.” All the more so because I teach at a Christian university where any student in any discipline can reflect on biblical themes; for the story of Frederick Douglass’ self-education testifies abundantly to the liberating power of studying God’s word.