In June protestors in Hong Kong lifted their voices in protest of a bill that would allow China to extradite fugitives from Hong Kong. In a surprise to global audiences, one million protestors, many of them young adults, sang the praise anthem “Sing Hallelujah to the Lord.” The Christian character of the protests is complicated, as Justin Tse pointed out last month at the Anxious Bench. Christians and non-Christians alike swelled the chorus, and singing a Christian song had some pragmatic benefits such as providing political and legal cover for the protests. But on some level the protesters were deploying religion in service of social justice. It reminds me of a protest in the 1980s that also used Hallelujahs. But this one took place in the Philippines.

On February 22, Adalia “Bing” Bustamante, a staffer in the operations division of World Vision-Philippines, joined the revolution. With the Filipino masses, she chanted “Sobra na, tama na,” meaning “Enough! We’re not going to take it anymore.” They formed a human barricade just outside Camp Aguinaldo, the military headquarters of President Ferdinand Marcos. Bustamante and a swelling crowd of several hundred thousand, which came to be termed People Power, accused the president of rigging elections, assassinating political opponents, presiding over unnecessary martial law since 1972, and not caring for the poor. They also sought to shield two high-level defectors of Marcos’s dictatorial regime.

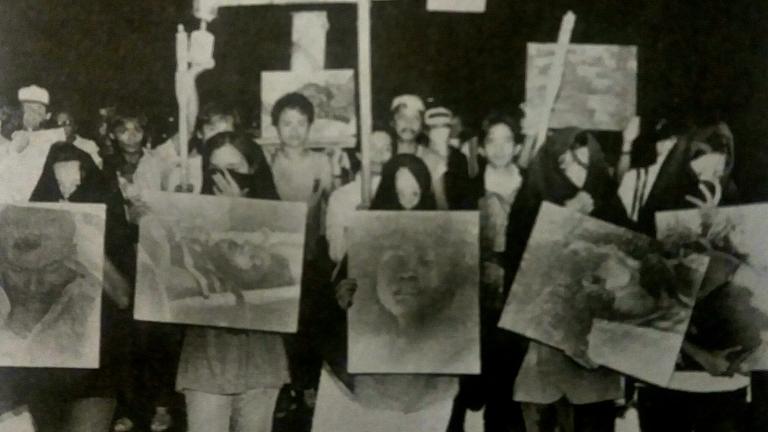

The atmosphere was both festive—a wall of yellow flags, posters, tents, and protesters extended five miles either way—and terrifying given the object of their protest. Marcos, a brutal dictator propped up by U.S. military bases on the island and Ronald Reagan’s political support, had been in power for nearly two decades. Helicopters and fighter pilots, waiting on instructions from the embattled dictator, circled overhead.

For Bustamante the dangerous protest was a “revolution of love” driven by her evangelical faith. At her day job, located only six kilometers away at World Vision headquarters in metro Manila, she went to daily chapel and encountered passages of scripture—“Let justice roll on like a river, righteousness like a never-failing stream” (Amos 5:24)—that compelled her toward the barricades. In turn, the protest, which immersed her in prayer and conversation with other protesters, reinforced her faith. “Being part of the human barricade,” she wrote, “was holistic ministry . . . that includes prayer, food, water, encouragement, intellectual, economic, everything.” “This is the Good News,” she proclaimed, “the Hope that we proclaim day after day. This is my Vision, being a part of World Vision Philippines.”

Bustamante was not the only evangelical in the barricades. In fact, the People Power movement was a turning point for evangelical social action in the Philippines. Having been taught by American missionaries that the only appropriate of method of social change was through personal conversion, most Filipino evangelicals for many decades had largely practiced quietism. But the social depredations of 1970s and 1980s—combined with the new emphasis on indigenous development and people’s participation among evangelicals associated with World Vision, InterVarsity, the Institute for Studies in Asian Church and Culture, and Diliman Bible Church—had changed the landscape.

In fact, during the month of February 1986, these “transformationalists,” as Al Tizon has called them, helped push the broader movement toward social action. Observers in fact watched the hermeneutical transformation in real time. At the beginning of the month, evangelicals, citing Romans 13, generally supported the dictator because he was the ruling authority. In fact, on February 14, the Philippine Council of Evangelical Churches (PCEC) issued a “Call to Sobriety,” which counseled its constituency to await the results of the election, not protest. On February 24, ten days after issuing the Call, PCEC issued a second statement that still showed hesitancy but nonetheless explained, “After much prayer, we have arrived at the moral conclusion that the legitimacy of the present administration should be questioned.” Almost immediately, many evangelicals went further than the PCEC’s mild rebuke, taking to the streets and declaring “war on Marcos with their feet and their actions.”

Evangelicals in fact became critically important to the larger movement. Initially led by the Catholic Church and Cardinal Sin, People Power took a blow when Marcos shut down the Catholic station Radio Veritas. But then the evangelical Far East Broadcasting Company (FEBC) took over. Announcer Eddie Villanueva and managing director Fred Magbanua broadcast updates, held marathon discussions on the use of civil disobedience, and ultimately urged listeners to join the barricades at Gate Two of Camp Aguinaldo.

Whole busloads, recalled Filipina evangelical social activist Melba Maggay, came from Bulacan, Batangas, Tagaytay, and other nearby provinces. She expected the sophisticated World Vision-like churches to appear, but she was surprised and impressed by the many “grassroots churches, simple folk who had come because they heard a call within them and knew it was right to come and be counted.” Isabelo Magalit, pastor of the Diliman Bible Church, acted as the “commander-in-chief” of an evangelical contingent in the barricade. Unarmed except for Bibles and hymnbooks, Magalit’s troops sought to avert a shooting war by creating a civilian buffer. “We believed in the safety of numbers, but our faith was in God,” he preached. In the end, even PCEC joined in. Jun Vencer, its general secretary, went to the airwaves to urge FEBC listeners to exercise “prayer power” by meeting in churches to pray for the success of the nonviolent revolution. He also visited the barricades and sent tents, food, and medicines.

The protest worked. Crowds of women and children offered candy and cigarettes to the soldiers. Evangelicals standing beside Catholics, they appealed for peace, placing flowers on the mouths of cannon. Tanks driven by gunners with tears in their eyes were ordered to ram through the barricades, but instead they turned back. On the second day Air Force officers commanded to bomb the camps refused. By the third day most of the military defected to the people. And on the fourth day, February 25, Marcos fled, whisked away by U.S. Air Force HH-3E rescue helicopters and planes to Anderson Air Force Base. News of his departure at 10:30 p.m. sparked a celebration. In a final demonstration of “people power,” deafening cheers broke out. Protesters danced in the streets and sang the Hallelujah Chorus. Bustamante declared, “It was God power working through people power which ousted a despotic and immovable ruler of 20 years.”

Filipinos associated with World Vision stood as a case study in how evangelicals could spearhead social action in a progressive direction. As Corazon Aquino took office, CBS reporter Bob Simon declared, “We Americans like to think we taught the Filipinos democracy. Well, tonight they are teaching the world.” Filipino evangelicals echoed Simon, calling their American “sisters and brothers to repentance … for past apathy and to become engaged in nonviolent struggle for justice, human rights, and freedom in the Philippines.” World Vision International president Ted Engstrom agreed, warning that the “euphoria accompanying the Philippines’ ‘revolution of prayer’ may soon turn to disappointment” if long-term, structural problems were not solved. World Vision, not seeing simple solutions in American power or mass evangelism, urged close attention to the severe economic and health problems of the nation.

This is an obscure narrative, one typically overshadowed by a different side of evangelicalism. Three years before these Filipino protests, President Reagan delivered his “Evil Empire” speech to a meeting of the National Association of Evangelicals. Advocating a hardline approach that would “write the final pages of the history of the Soviet Union,” Reagan was repeatedly interrupted by applause. Jerry Falwell, leader of the Moral Majority, threw his support behind Ferdinand Marcos. After being lavishly hosted by the Filipino strongman in Manila, Falwell told American critics to quit “bellyaching” about his corruption and brutality, instead urging Washington to put “its money where its mouth is” to prevent a communist takeover in a vulnerable region. Moreover, Filipino fundamentalists touted strong pro-Americanism and unfettered capitalism. This narrative of a resurgent fundamentalism—of Reagan’s triumphalism overwhelming Carter’s theology of limits—grabbed headlines in the 1980s and rightly remains the focus of sustained scholarly attention.

But other sectors were moving in a different direction. In 1986 evangelicals at the Far East Broadcasting Company and at World Vision helped lead a “People Power” movement that opposed Marcos in the mid-1980s. Billy Graham, after increased international travel in the 1970s and 1980s, pled for an end to the arms race, apartheid in South Africa, and “America’s exploitation of a disproportionate share of the world’s resources.” In this age of Trump, Falwell, and Franklin Graham, “People Power” reminds us that evangelicalism has taken a multiplicity of forms both geographically and historically.