Through writing about church history in many different eras, I have acquired a long standing interest in apostates and apostasy. In so many ways, apostates stubbornly refuse to fit into our normal assigned categories. We spend a huge amount of time addressing why people convert to particular faiths and causes, but rather less on why they leave. In the history of Christianity, this latter angle is actually a vast topic, and one that hugely occupied the minds of church councils and bishops through the centuries, especially in times of persecution. Let me offer a couple of thoughts about this here – on the matter of apostasy – and I’ll return to the point in later columns. Perhaps you can’t understand the nature of faith without analyzing how and why it is lost.

The word apostasia means something like defection, abandonment, or falling away, and it occurs a c0uple of times in the New Testament, in Acts 21.21 and 2 Thessalonians 2.3, where it suggests a grand event in the end times. That is quite apart from general references to different kinds of falling away, most famously in the parable of the Sower.

As he was scattering the seed, some fell along the path, and the birds came and ate it up. Some fell on rocky places, where it did not have much soil. It sprang up quickly, because the soil was shallow. But when the sun came up, the plants were scorched, and they withered because they had no root. Other seed fell among thorns, which grew up and choked the plants. (Matt 13.4-7)

But what about the history of actual apostates?

One of the very earliest external sources for church history is the famous letter of Pliny to the Emperor Trajan, written in 112 AD in the region of Bithynia and Pontus, at a time when the New Testament was still a very fluid state. Pliny is widely quoted on the nature of early belief and liturgy, but we may pay rather less notice to what he says about ex-Christians, who were already a substantial group. As he writes,

A libel was sent to me, though without an author, containing many names [of persons accused]. These denied that they were Christians now, or ever had been. They called upon the gods, and supplicated to your image, which I caused to be brought to me for that purpose, with frankincense and wine; they also cursed Christ; none of which things, it is said, can any of those that are really Christians be compelled to do; so I thought fit to let them go. Others of them that were named in the libel, said they were Christians, but presently denied it again; that indeed they had been Christians, but had ceased to be so, some three years, some many more; and one there was that said he had not been so these twenty years. All these worshiped your image, and the images of our gods; these also cursed Christ. [my emphasis]

Other versions suggest the last person cited had left the faith as much as twenty five years previously.

Assume for the sake of argument that these dates are more or less correct, and not just “Christian? Oh yeah, but that was twenty years ago! Nothing serious, just a phase.” We would have to imagine a man converted in the 70s, say, who abandoned the faith around 90, and was thus a member of the church during a time of effervescent creativity in Christianity, at the time when for instance the gospels were being written – and who then gave it up, for whatever reason.

I am speculating completely, but I wonder why he defected? He lost interest? Pressure or threats from neighbors or family? Pressure from pagans or Jews? Quarrels within the church? Can we just assume that he “had no root,” as in the parable? Or was he a passionate believer who faced a spiritual crisis? And what did he convert from, and back to? Was he a pagan who dabbled in Christianity, for three years or for thirty? Or was he a Jew who explored the Jesus movement, and then returned to mainstream faith. Would the Romans have forced a Jew to worship the emperor’s image? It all cries out for discussion, if only we had anything whatever to go on. We’ll never know.

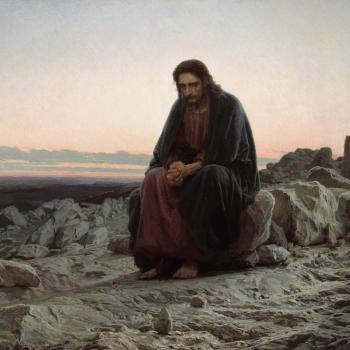

And of course, there are excellent reasons why we don’t have more to go on, namely who is going to write about such people? We hear a lot about the stubborn believers who held out to the end, but far less about the ones who compromised – “He’s gone, good riddance!” Go to an art gallery and count the Old Master images of martyrs who persisted to the end – a daunting task. Now count the great apostates, if you can find any.

Hmm, Peter as he heard the cock crow, maybe.

Nor do we hear much about that other interesting category, those who left but who would would turn back to the faith again in later years. And there must always have been plenty of those, especially in times of persecution and violence. If you ever read Shusaku Endo’s stunning novel Silence, he gives a terrific sense of this subculture of serial apostates and floating believers, in the Japan of the seventeenth century, and of the psychology of individual turncoats. (I wish I could claim to have invented the phrase “serial apostates”).

Also from that early modern era, there is a sizable literature on Christians who deserted the faith to flight for Islam, mainly in the Mediterranean world – those who denied, or “renegades.” Tobias P. Graf has a 2017 book on The Sultan’s Renegades: Christian-European Converts to Islam and the Making of the Ottoman Elite, 1575-1610; and Claire Norton edited a 2017 collection of essays on Conversion and Islam in the early modern Mediterranean. Dr. Norton also published an article on “Lust, Greed, Torture, and Identity: Narrations of Conversion and the Creation of the Early Modern Renegade.” Now that’s a title.

So what are the other big eras for research and writing? Christian Hornung has a fine academic study of related themes in early Christianity, in his 2016 book Apostasie im antiken Christentum (Brill) but I don’t believe it’s been translated yet. It covers issues of theology, church discipline and pastoral care, mainly from the fourth century onward.

There’s a big literature on Donatism, which is not exactly full-scale apostasy, but which touches on precisely the same issues. That involved clergy and church leaders who handed over scriptures to the authorities in times of persecution, thus becoming “traitors” (traditores, from traditor, literally, a “hander-over”). The issue then was not whether they had left the church entirely, but what should be the standards applied to those who had erred so badly, and how could they resume their previous roles and prestige? Many Donatists held rigorist and perfectionist views on these matters. If a bishop was a traditor, then he could not lawfully ordain anyone, so the credentials of the person ordained were invalid. The Donatists held that existing clergy had betrayed the church, and schisms followed (See Richard Miles, ed., The Donatist Schism, 2016).

In late Roman North Africa, struggles over Donatism often amounted to a virtual civil war among Christians, and came close to destroying Roman authority. Donatist controversies took up a lot of St. Augustine’s time as bishop. Out of the arguments came a lot of later theories about separating the sacred nature of the priestly office from the sinful qualities of the individual office holder.

As I will argue over my next couple of posts, you actually have a great range of issues and questions that almost define themselves as book chapters: the idea of apostasy; reasons for abandoning a church; the nature of apostasy – actual or clandestine; degrees of apostasy; double faith, double lives, and double minds; the motives for return; church responses; and so on. It cries out for comparative discussion over many different eras and places.

Help me here: does anything like such a book actually exist already?

More on this next time.