Yesterday, the trial began for Dr. Scott Warren, a geographer and volunteer with the humanitarian aid organization No More Deaths, a ministry of the Unitarian Universalist Church of Tucson. The Department of Justice alleges that Warren violated smuggling laws in his efforts to “conceal, harbor and shield from detection” undocumented immigrants from Mexico—a unique prosecution under human smuggling laws, which in Southern Arizona are typically used against those who smuggle for profit, rather than aid workers like Warren. Facing the possibility of twenty years in prison for these felony charges, Warren argues that his provision of food, water, shelter, and first aid to migrants was a just and necessary act of compassion, especially in the harsh Sonoran Desert, where dozens of migrants die every year due to the brutal conditions. As he explained in an op-ed in the Washington Post on Tuesday,

In Ajo, my community has provided food and water to those traveling through the desert for decades — for generations. Whatever happens with my trial, the next day, someone will walk in from the desert and knock on someone’s door, and the person who answers will respond to the needs of that traveler. If they are thirsty, we will offer them water; we will not ask for documents beforehand. The government should not make that a crime.

The promise to offer water to the thirsty echoes a verse in Matthew 25 commonly cited by faith-based immigration justice activists—“for I was hungry and you gave me food, I was thirsty and you gave me something to drink, I was a stranger and you welcomed me”—and illuminates an important aspect of Warren’s humanitarian work: that he sees his actions as arising from his spiritual and religious commitments.

The religious dimensions of Warren’s volunteer work with No More Deaths gained attention earlier this month, when he was on trial for misdemeanor charges for similar aid work in Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refugee in June 2017. On May 7, Warren testified that his efforts to leave water and food for migrants in Cabeza Prieta express his sincerely held religious beliefs. He explained that the desert near Ajo is “sacred” and contains the remains of dozens of migrants who died during their journey. Whenever he encounters these remains, he completes a ritual that offers “silent acknowledgement” of the person who died. Moreover, he feels a religious obligation to prevent further death. “[These deaths are] unconscionable to me and it requires me to act and to do something,” he said.

Others have affirmed that Warren’s work was, indeed, religious work. “Scott has a deeply held spiritual belief about the land he lives on,” said Justine Orlovsky-Schnitzler, the spokesperson for No More Deaths. “He feels that every human life is sacred and deserves to be acknowledged.” In addition, Katherine Franke, director of the Law, Rights, and Religion Project at Columbia Law School, criticized the Department of Justice for its “contradiction in how they support religious liberty.” Franke, who filed an amicus brief supporting Warren’s religious claims, argued that Warren’s prosecution offers a “troubling message” to people of faith who, like Warren, “are interested in the sanctity of life” and demonstrate that concern for life through humanitarian aid to vulnerable people, including migrants.

Warren’s argument that his actions are religious may draw skepticism from those who adhere to a narrow notion of what constitutes religion. The provision of food, water, and shelter to migrants did not occur in a church or a temple, nor is his desert ritual a familiar sacrament like Holy Communion or confession. However, a look to the past reveals that Warren is by no means the first person to describe the work of caring for migrants as an expression of religious faith. Across the denominational and theological spectrum, diverse people of faith, including many American Christians, have long embraced service to migrants as a religious duty rooted in the Biblical imperative to “welcome the stranger” and to “love thy neighbor.”

For example, faith-based refugee resettlement work—which is one of the primary avenues through which refugees in the United States receive assistance—usefully illustrate how American Christians have embraced service to migrants as a practice that expresses deeply-held religious beliefs. In my research on religious organizations involved in Southeast Asian refugee care, I found that volunteers with church sponsorship projects and faith-based charities consistently described their refugee work as religious in a few main ways. Some saw refugee care as a ministry of hospitality and a chance to aid “the least of these.” In explaining their service, they listed acts of Christian kindness and charity—including feeding the hungry, clothing the naked, and offering shelter to the weary—and connected these works to the core responsibilities of sponsoring refugees for resettlement. Other people considered their refugee work to be an outgrowth of their progressive Christian values—namely, their opposition to the Vietnam war, their support for peace-making, and their social justice commitment to eradicating poverty and racism. Still others saw refugee resettlement work as a domestic extension of overseas missionary work and an opportunity to save souls. However resettlement volunteers framed it, people generally considered aiding refugees to be a Christian practice—a form of “lived religion” and, for many, an expression of what scholar Nancy Ammerman has described as “Golden Rule Christianity.”

Most people embraced a combination of these ideas, as was the case with Maryann Lund, a volunteer at Marine Corps Base Camp Pendleton in the spring of 1975. A pastor’s wife and a volunteer with Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service, Lund felt called by both her government and her church to aid Vietnamese refugees displaced by war. At Camp Pendleton, located fifty miles north of San Diego, Lund was one of hundreds of religious volunteers who helped to resettle over a hundred thousand Vietnamese refugees airlifted from staging areas in the Pacific and delivered to temporary camps at military sites in the United States that year.

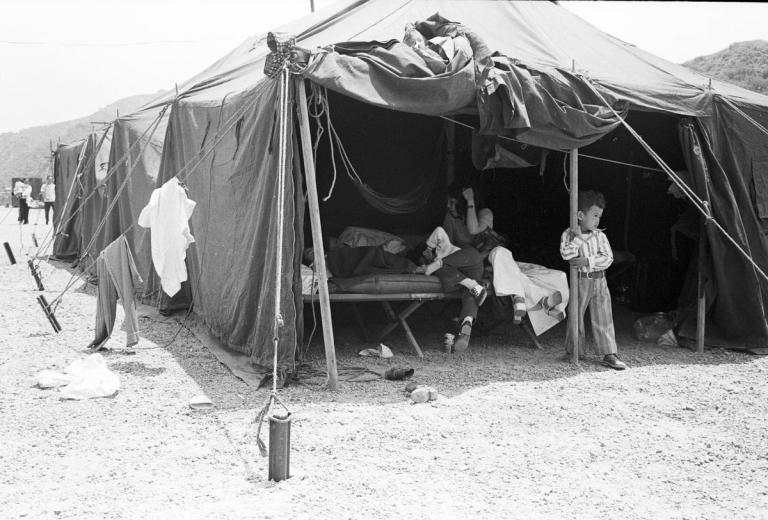

For Lund, the work of resettlement provided an exhilarating religious awakening. It was in the refugees at Camp Pendleton, she explained, that she and her husband first truly “saw the face of Christ.” She found the daily work of feeding the hungry and comforting the grief-stricken was a holy encounter with Jesus, as well as an opportunity to follow Jesus’s teachings. Quoting Matthew 25, Lund described the Biblical basis for her volunteer work with refugees. When she served meals and washed the clothing of refugees, she explained that she was honoring verses 35 and 36: “I was hungry and you gave me food, naked and you clothed me.” When she spent time with the people who lived in the prison-like conditions of Camp Pendleton, where a field of tents housed “huddled masses yearning to be free,” she acted on the call to show mercy to the lonely and unfree: “I was in prison and you came to visit me.” When she saw the gratitude of refugees who were sponsored and resettled by Lutheran congregations across the country, she lived out the call for Christian hospitality: “I was a stranger, and you took me in.”

Lund hoped that her story would encourage other Lutherans to contribute to the resettlement effort. In making her case, she echoed the arguments made by government officials promoting refugee sponsorship as an chance to help refugees achieve self-sufficiency. Sponsors, she said, “would provide for the prisoner’s needs until he or she could stand alone, self-supporting and truly free.” But Lund’s message centered primarily on presenting refugee care as a unique religious ministry. “You are the ones who can minister to these ‘Christs’ through our love and assistance,” she said. “…A thrilling experience awaits you as you share your gifts from the hand of a loving Father with others of his creation. You are his hands and heart in ministry, in holy spirit, [that] lives and moves to call, gather, enlighten and sanctify.”

To be sure, not every person of faith involved in Southeast Asian refugee resettlement described their work as religious. Some volunteers found themselves pulled into resettlement work for other, decidedly non-religious reasons, even if they worked with religious agencies and churches. For example, Mark Franken, who later became director of the Migration and Refugee Service of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, got his start in refugee work because he had befriended a Vietnamese man during his military service. Later, while sheltered at a refugee camp in Fort Indiantown Gap in 1975, this friend asked Franken for help in finding a new home, and Franken, out of friendship and loyalty, obliged. Other Christians became involved in refugee work because they felt a Cold War-era responsibility to aid people who had been America’s anti-communist allies, and still others supported resettlement efforts as an expression of their long-standing opposition to the Vietnam War. And, of course, not every American person who volunteered to help with Southeast Asian refugee resettlement was Christian; many Jews, Buddhists, and non-religious people were involved, too.

But the reality is that much of the American effort to aid Southeast Asian refugees was powered by Christian volunteers who, like Scott Warren, considered the work of aiding and welcoming migrants to be a religious duty, rooted in sincere religious beliefs. Importantly, unlike Warren’s case, the fact that Christian resettlement volunteers saw their work as religious was something that the U.S. government readily welcomed. The U.S. government relied on religious voluntary agencies to resettle the great majority of the one million Southeast Asian refugees who came to the United States in the 1970s and 1980s. The generous donation of time, talent, and money by Christian individuals and churches greatly offset the cost of resettlement, and, ultimately, it was financially advantageous for the U.S. government to have Christian volunteers embrace resettlement as a religious ministry; church volunteers contributed openhandedly, allowing the U.S. government, in turn, to be comparatively stingy.

Importantly, while it might have served the government’s interests to encourage resettlement volunteers to see their work as a righteous Christian calling, the case is different for Scott Warren and the volunteers of No More Deaths, who have stridently criticized the U.S. government’s draconian border policies as inhumane, immoral, and inconsistent with their values. To oppose these policies, and to show compassion for migrants, is, in their view, a fundamental religious calling. Whether the courts agree, however, is uncertain, though that uncertainty is perhaps the least surprising aspect of this case. As with all things related to religion in America, the question of what gets to count as religious remains contentious—and it has less to do with authentic beliefs and practices and much more to do with money, politics, and power.