It’s Lunar New Year this week, and across the country, Chinese Americans are ushering in the Year of the Pig with feasts and family gatherings. In recognition of the holiday and the large population of Asian Americans who observe it, public schools in New York City held no classes on Tuesday, an effort to accommodate Chinese and other Asian American children in the same way that they accommodate Christian children celebrating Christmas, Jewish children celebrating Rosh Hashanah, and Muslim children celebrating Eid al-Adha. Lunar New Year, at least in the eyes of the New York City Department of Education is an important holiday. But is Lunar New Year—like Christmas, Rosh Hashanah, and Eid al-Adha—a religious holiday? And are Lunar New Year rituals that Asian Americans practice religious rituals?

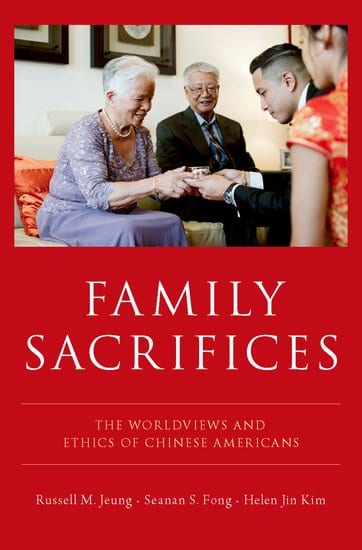

At the heart of these questions are fundamental issues in the study of religion—namely, what counts as religion and who has (or who doesn’t have) a religion. On these matters, the spiritual beliefs and practices of Chinese Americans offer a particularly useful and illuminating case study. Surveys indicate that a high proportion of Chinese Americans are religious “nones.” However, as Russell Jeung, Helen Kim, and Seanan Fong point out in their new book, Family Sacrifices: The Worldviews and Ethics of Chinese Americans (Oxford University Press, 2019), these surveys rely on a Western paradigm of religion and thus fail to adequately reflect the spiritual lives of Chinese Americans. What’s needed, they argue, is an alternative framework that is rooted in Chinese beliefs and practices. Their findings complicate common understanding of Chinese American religious life, as well as the Western religious categories on which scholars of religion rely too readily.

Jeung, Kim, and Fong were kind enough to answer a few questions about their thought-provoking research.

MB: What are the basic arguments of your book?

RJ/HK/SF: Family Sacrifices: The Worldviews and Ethics of Chinese Americans makes two arguments. First, even though surveys show that Chinese Americans are the most non-religious group in the United States, they do hold deeply-held values and practice regular rituals that they consider ethical. We term these values and rituals as Chinese American familism, because the family is the primary narrative by which they derive meaning and purpose.

Second, we develop a new theoretical framework to examine Chinese Americans and other religious “nones.” We argue that religious nones shouldn’t be understood in terms of the absence of beliefs and religious affiliations. Instead, using a Chinese term, liyi, we suggest that religious nones like Chinese Americans do hold to a host of values and rituals which reveal a different kind of spirituality than the Western paradigm of religion presupposes.

In your book, you discuss how “Chinese American familism” is “a lived tradition that prioritizes family interdependence and right relationships, through the meaningful rituals of being family.” Since Chinese families are celebrating Lunar New Year this week, could you illustrate how different individuals and families practice this lived tradition through the specific rituals and customs of this holiday?

Over ninety percent of second-generation Chinese Americans continue to celebrate Chinese New Year’s. However, the meaning of the special foods, taboos, and practices of this festival varies from individual to individual. They range on a continuum of belief and of symbolic meaning. Some think of these rituals as spiritually efficacious, that by doing them they feed their ancestors’ spirits and increase their chances of luck. Others, on the other hand, think of these rituals as ethnic customs that symbolize the traditions and family values of Chinese. They maintain these practices to celebrate their Chinese heritage, but not necessarily to honor spirits that they think are still around.

Your work shows that Chinese Americans have hybrid religious lives. How do Chinese Americans integrate liyi and familism with other religious traditions, such as Christianity?

Chinese Americans of all religious traditions, including those who say they are not religious, integrate the rituals and values of familism into their religious repertoires. For example, Chinese American Christians might highlight the commandment to honor one’s father and mother more than other groups. They tend to see the church as a family, in contrast to other metaphors like the church as a refuge or a body. Further, Chinese American Christians have become more politically involved around issues that they see relating to the family than other issues. That’s why conservative congregations have mobilized around same-sex marriage rather than, say, affirmative action or healthcare.

Your work is provocative because it challenges people to rethink assumptions about religious “nones,” the subject of increasing scholarly attention. How does an indigenous Chinese perspective offer new ways of understanding this group?

Our main analytical critique of extant sociological accounts of “religious nones” is that most of these studies take for granted the Western paradigm of religion, especially its emphasis on belief and belonging. The overwhelming perspective in the literature is that religious nones are those who do not believe in God or belong to a church, reflecting a highly Christian-centered view of non-religiosity. While conducting interviews through snow-ball sampling, we noticed in our data that, in spite of their purported non-religiosity, our subjects expressed cherished values and ethics, and led lives of devotion and commitment – even the atheists. Yet their moral boundary system defied the Western categorizations of belief/non-belief or belonging/non-belonging and centered on the practice of right relations.

So, instead of using the category of “religious nones,” which connoted a sense of absence, we re-appropriated an indigenous Chinese term as our theoretical framework to understand our data: liyi (禮義). Specifically, the theory of liyi examines (1) what moral practices, or li, a given group ritually maintains and values as well as (2) how they understand and rightly act in their most important relationships, or yi. This lens helped us to more clearly illuminate the presence of the values, ethics, practices and rituals that we saw in the data. For example, using a liyi framework, we became attuned to patterns in how our subjects sought to maintain right relations through practices such as ancestor veneration, family meals, and lunar new year celebrations, which reflected their ethical concerns and moral responsibilities. Had we used non-belief and non-belonging as the primary frame, we could not have understood the significance that these practices had in structuring our subjects’ everyday lives.

By considering the religious lives of Chinese Americans, Family Sacrifices also illuminates the limitations of the category of religion, which is rooted in Western assumptions. What are the implications of your work, not just for scholars of Chinese American religion, but for all scholars of religion?

The “rise of the nones” is an emergent phenomenon garnering much attention in the United States, but non-religiosity is a historically an old phenomenon. Indeed, for most of its history, China could have been classified as having no religion, and in the 19th-century other Americans deemed Chinese Americans as “heathens” for their lack of Christian faith. We, therefore, ask: What if we understood the unaffiliated in America from the perspective of Chinese Americans, the historically “heathen,” whose parents never belonged to a church and defended “no religion” before it became it became a trend among millennials? We conclude that if Chinese are historical forerunners to the contemporary rise in nones in the United States, then the theory of liyi is useful for not only understanding Chinese Americans but also millennial American “nones” in general. Thus, our study points to the limitations of “religion” as a lens and offers an alternate indigenous Chinese lens through which to see human values, ethics, practices and rituals.

When employing liyi as a lens, one begins with different assumptions. One might replace the question, “Why are American millennials increasingly nonreligious?” with the following: “What deeply held values are expressed in the rituals to which millennial religious nones devote themselves?” Another question framed by a theory of liyi is “What practices help nonreligious American millennials maintain their ultimate priorities?” Instead of investigating why non-religiosity is growing among millennial nones—which prioritizes a belief and belonging framework—one might instead employ a liyi framework to understand how millennials are actually engaged in practices (li) centered around forging right relations (yi). Family Sacrifices suggests that a significant portion of these millennial nones hold onto moral boundary systems of liyi, practice-centered means of forging right relations, just as Chinese Americans do.