To its credit, Patheos encourages those who read blog posts also to read books. But last month Beth noticed that women were absent from recent Patheos Book Club selections aimed at this particular channel’s readers:

Just scrolled through the @PatheosEvang book club featured offerings—all by men and including Mark Driscoll ; let’s include women for our 2019 resolution pic.twitter.com/9dom9P8qmr

— Beth Allison Barr (@bethallisonbarr) December 26, 2018

Hopefully, it’s just a blip; Patheos has previously featured women like Debra Hirsch, Carolyn Custis James, and Janet Wehr. But seeing so many books by men prompted Beth, Kristin, and me to put together our own book club for 2019: 12 recent, forthcoming, or classic books by women that we’d love to see Patheos Evangelical readers read.

(Rather than including Amazon links on this list, I’d encourage you to buy from Byron Borger, proprietor of what our friend John Fea recently called “The Best Christian Bookstore in America.”)

Anna Akhmatova, The Complete Poems of Anna Akhmatova, trans. Judith Hemschemeyer (Canongate, 2000).

I’ve written my share of this post from hostels in London and Paris, where I’m leading a World War I travel course that includes several days on the former Western Front. Unfortunately, that focus means that I didn’t assign my students some of the first haunted works by a young poet who wanted to become nothing less than a 20th century version of Pushkin. “Low, low hangs the empty sky,” wrote Anna Akhmatova in July 1914, “And a praying voice quietly intones: / ‘They are wounding your sacred body, / They are casting lots for your robes.'” It’s an early example of how this Orthodox poet drew on biblical and liturgical language to wrestle with doubt and suffering.

I’ve written my share of this post from hostels in London and Paris, where I’m leading a World War I travel course that includes several days on the former Western Front. Unfortunately, that focus means that I didn’t assign my students some of the first haunted works by a young poet who wanted to become nothing less than a 20th century version of Pushkin. “Low, low hangs the empty sky,” wrote Anna Akhmatova in July 1914, “And a praying voice quietly intones: / ‘They are wounding your sacred body, / They are casting lots for your robes.'” It’s an early example of how this Orthodox poet drew on biblical and liturgical language to wrestle with doubt and suffering.

Perhaps her greatest such work is an extended “Requiem” written over three decades of Stalin’s oppression. (The translator’s preface notes that when Akhmatova was expelled from the Union of Soviet Writers, she was disparaged as the “half-nun, half-harlot.”) Written from the point of view of Akhmatova’s fellow political prisoners, Requiem‘s dedication seems oddly appropriate to our own dispiriting time: “We rose as if for an early service, / Trudged through the savaged capital / And met there, more lifeless than the dead; / The sun is lower and the Neva mistier, / But hope keeps singing from afar.” Such poems “aren’t rosy,” singer-songwriter and Akhmatova admirer Iris Dement says, “but she doesn’t succumb to despair or bitterness either. She’s in the fight and yet manages to hold fast to love and truth.” (Chris)

Amy Collier Artman, The Miracle Lady: Kathryn Kuhlman and the Transformation of Charismatic Christianity (Eerdmans, coming March 2019)

Artman’s book about one of the most famous faith healers of the 20th century is still a couple months away from publication. But listening to her talk about Kuhlman last fall at our Conference on Faith and History session on non-traditional spiritual biographies hooked my interest. Here’s the Eerdmans description:

On October 15, 1974, Johnny Carson welcomed his next guest on The Tonight Show with these words: “I imagine there are very few people who are not aware of Kathryn Kuhlman. She probably, along with Billy Graham, is one of the best-known ministers or preachers in the country.” But while many people today recognize Billy Graham, not many remember Kathryn Kuhlman (1907–1976), who preached faith and miracles to countless people over the fifty-five years of her ministry and became one of the most important figures in the rise of charismatic Christianity.

In The Miracle Lady Amy Collier Artman tells the story of Kuhlman’s life and, in the process, relates the larger story of charismatic Christianity, particularly how it moved from the fringes of American society to the mainstream. Tracing her remarkable career as a media-savvy preacher and fleshing out her unconventional character, Artman also shows how Kuhlman skillfully navigated the oppressive structures, rules, and landmines that surrounded female religious leaders in her conservative circles.

Given how men writing about men have dominated this corner of the publishing market, it’s good to see The Miracle Lady join a series that includes biographies by Nancy Koester (Harriet Beecher Stowe) and Edith Blumhofer (Fanny Crosby). (Chris)

Kate Bowler, Everything Happens for a Reason: And Other Lies I’ve Loved (Random House, 2018).

Nearly every person of faith will, at one time or another, come to a place where their faith is tested. Often, it is tragedy that sparks a crisis of faith—a crisis that is perhaps especially acute for those who have, wittingly or not, imbibed the teachings of the prosperity gospel. Here is where Kate Bowler can instruct us like no other. Diagnosed with stage 4 cancer, Kate also happens to be the foremost historian of the prosperity gospel. She is also a stunningly beautiful writer, and beautiful human being. Here’s what I wrote in a reflection on Kate’s book last year at The Anxious Bench:

As a religious historian, I ought to have been drawn to Kate’s reflections on the prosperity gospel, to how her expertise in that tradition shaped her own encounter with catastrophe. And it’s true that her scholarly background brings depth and unique insight to this book.

But in truth, I really just wanted to listen to Kate talk. I’m not sure if her reflections on life and death are more profound because she knows everything there is to know about the prosperity gospel, or if she wrote such a powerful book about the prosperity gospel because she has a depth of insight, because she has a heart for what it is to be human. I think, perhaps, the latter. (Kristin)

Austin Channing Brown, I’m Still Here: Black Dignity in a World Made for Whiteness (Convergent Books, 2018).

Austin Channing Brown doesn’t pull any punches in her memoir of growing up and coming of age as a black girl in majority-white schools, churches, and organizations. For black Christians who have walked a similar path, and for white Christians who have sought to address “racial justice” and achieve greater “diversity,” Austin provides a roadmap of the frustrations and the possibilities she encountered. As her publisher puts it: “For readers who have engaged with America’s legacy on race through the writing of Ta-Nehisi Coates and Michael Eric Dyson, I’m Still Here is an illuminating look at how white, middle-class, Evangelicalism has participated in an era of rising racial hostility, inviting the reader to confront apathy, recognize God’s ongoing work in the world, and discover how blackness–if we let it–can save us all.” (Kristin)

Austin Channing Brown doesn’t pull any punches in her memoir of growing up and coming of age as a black girl in majority-white schools, churches, and organizations. For black Christians who have walked a similar path, and for white Christians who have sought to address “racial justice” and achieve greater “diversity,” Austin provides a roadmap of the frustrations and the possibilities she encountered. As her publisher puts it: “For readers who have engaged with America’s legacy on race through the writing of Ta-Nehisi Coates and Michael Eric Dyson, I’m Still Here is an illuminating look at how white, middle-class, Evangelicalism has participated in an era of rising racial hostility, inviting the reader to confront apathy, recognize God’s ongoing work in the world, and discover how blackness–if we let it–can save us all.” (Kristin)

Lynne Hybels, Nice Girls Don’t Change the World (Zondervan, 2005).

This book changed my life when I first read it in 2009. I, like Lynne Hybels, was a nice Christian girl who did (most) things right. Like Lynne Hybels, I too was absolutely miserable while trying to force myself into the expected role for Christian women. Her book opened my eyes to the possibility of “biblical womanhood” as a myth. It is heart wrenching, especially in light of what we now know about her marriage to Bill Hybels. But her story still can help us better understand the plight faced by so many, many evangelical women today, and—most importantly—her journey still gives us hope. As she writes, “Never doubt that a community of thoughtful, committed women, filled with the power and love of God, using gifts they have identified and developed, and pursuing passions planted in them by God—never doubt that these women can change the world.” (Beth)

Margery Kempe, The Book of Margery Kempe, trans. Liz Herbert McAvoy (Boydell and Brewer, 2003).

I often wonder what John Piper would do with Margery Kempe. When the Archbishop of York (the second most important ecclesiastical position in England) demanded that she stop teaching and preaching, Margery Kempe looked him in the face and said, “No.” She explained that it was because “I think the Gospel gives me leave to speak of God.” And she got away with it. Confronting Margery, a fifteenth-century English woman, forces us to question modern ideas about biblical womanhood. While I think it is great to read the unabridged version of Margery Kempe (like the Penguin edition), I actually think it might be better for those new to medieval Christianity to start with McAvoy’s abridged version. Margery is absolutely exasperating, but she is also absolutely invested in following Jesus and doesn’t let her husband, family, or even priest get in the way. (Beth)

Linda Kay Klein, Pure: Inside the Evangelical Movement That Shamed a Generation of Young Women and How I Broke Free (Touchstone, 2018).

For evangelicals who grew up in the purity movement, for parents who taught their kids “purity” and sent them to churches and youth groups that reinforced this message, for those who have left evangelicalism and those who have stayed, Linda Kay Klein’s book will speak to you. As an insider to the movement, Klein writes from personal experience. But she also brings academic expertise to the subject of evangelical teachings on sex and gender. Having conducted dozens of interviews, she is able to go beyond the limitations of memoir to speak to the broader purity movement and its ongoing repercussions. It is a painful read, but a challenge that the evangelical church must reckon with. (Kristin)

For evangelicals who grew up in the purity movement, for parents who taught their kids “purity” and sent them to churches and youth groups that reinforced this message, for those who have left evangelicalism and those who have stayed, Linda Kay Klein’s book will speak to you. As an insider to the movement, Klein writes from personal experience. But she also brings academic expertise to the subject of evangelical teachings on sex and gender. Having conducted dozens of interviews, she is able to go beyond the limitations of memoir to speak to the broader purity movement and its ongoing repercussions. It is a painful read, but a challenge that the evangelical church must reckon with. (Kristin)

Danielle L. McGuire, At the Dark End of the Street: Black Women, Rape, and Resistance—a New History of the Civil Rights Movement from Rosa Parks to the Rise of Black Power (Knopf, 2010).

This book is a must-read for all Americans. I assigned McGuire’s book in an intro course on women’s history last fall, and I have never had students more engaged with a book. McGuire tells the brutal story of the sexual violence black women have long endured at the hands of white men, and how their resistance to that violence sparked the civil rights movement. Filled with gripping stories and based on prodigious research, McGuire’s book is a tour-de-force. Why does this book make the list for evangelicals in particular? At a time when the white evangelical church is struggling to come to terms with its own legacy of racial injustice and proliferation of abuse, this is essential reading. Add to that the fact that the majority of white Southerners in this narrative were, of course, white Christians—indeed, white evangelicals. From #MeToo to police violence to mass incarceration, this book will open one’s eyes to the ways in which the past continues to haunt the present. (Kristin)

Dorothy L. Sayers, Are Women Human? (Eerdmans, 2005; 1971 first printing).

Mystery writer, medieval scholar, theologian, Christian apologist, playwright, and the almost Inkling everyone forgets, Dorothy L. Sayers was one of the first women to graduate from Oxford University. She was a scholar, writer, and Christian apologist just like C.S. Lewis, but instead of teaching at university and writing books in her spare time, she earned her family’s daily bread through her pen. A feminist thread runs through many of her works (just check out Gaudy Night), but it is only in these essays that she confronts the woman question head on.

Mystery writer, medieval scholar, theologian, Christian apologist, playwright, and the almost Inkling everyone forgets, Dorothy L. Sayers was one of the first women to graduate from Oxford University. She was a scholar, writer, and Christian apologist just like C.S. Lewis, but instead of teaching at university and writing books in her spare time, she earned her family’s daily bread through her pen. A feminist thread runs through many of her works (just check out Gaudy Night), but it is only in these essays that she confronts the woman question head on.

Her argument is both simple and profound: women are human, just like men. Her proof of this absolute equality is even more profound — that Jesus died for women too. “Perhaps it is no wonder that the women were first at the Cradle and last at the Cross,” she wrote. “They had never known a man like this Man… A Prophet and teacher who never nagged at them, never flattered or coaxed or patronized…who took their questions and arguments seriously; who never mapped out their sphere for them, never urged them to be feminine or jeered at them for being female; who had no axe to grind and no uneasy male dignity to defend; who took them as he found them and was completely unselfconscious.” At less than 70 pages, this book won’t take much time to read, and it could very well change your attitude toward women. (Beth)

Theoloqui (theoloqui.net)

I’m cheating on my own premise here by including a group blog in place of a book… but this lets me recommend to your attention a diverse group of several more women instead of just one. Theoloqui started in 2015 with eight women connected to my home denomination, the Evangelical Covenant Church, reflecting on our six core theological affirmations. Always thoughtful and thought-provoking, the writers often challenged me to think anew about words and phrases that I used too easily or triumphantly. After a hiatus, Theoloqui returned in November with a new series of responses to the #MeToo movement. So especially if you’ve resonated with recent posts from Kristin and Beth on misogyny and sexual abuse in the church, let me encourage you to add Theoloqui to your reading list. (Chris)

Larissa Tracy, Women of the Gilte Legende: A Selection of Middle English Saints Lives (D.S. Brewer, 2012).

This is an inexpensive and excellent introduction to the world of European medieval women. Instead of the Proverbs 31 Woman and the silent, submissive wives of 1 Timothy 2 and 1 Corinthians, medieval Christians were regaled with a very different set of female exemplars. From holy transvestites to penitent prostitutes and mothers who abandon their children for God, these women were defiant, tenacious, wise, pious, and, confident; they were preachers, teachers, evangelists, and—above all—dedicated to serving God. Their stories remind us how big the Christian world really is and provides us with a much broader perspective on what it means to be a Christian woman. It is also short and a lot of fun. (Beth)

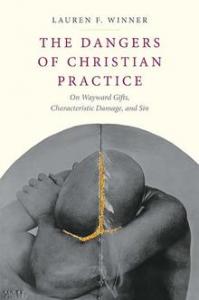

Lauren Winner, The Dangers of Christian Practice: On Wayward Gifts, Characteristic Damage, and Sin (Yale University Press, 2018)

After debuting with the unforgettable spiritual memoir Girl Meets God, historian Lauren Winner next wrote about the spiritual disciplines in Mudhouse Sabbath. But while that short book mostly celebrated the benefits of Jewish and Christian practices, Winner’s newest work warns of the dangers that can inhere to them. Starting with a survey of how supposed desecration of the Host led to anti-Semitic violence in medieval Europe and continuing with the prayers of slave-owning women, Winner considers “not primarily a practice’s propensity for fostering holiness (there are plenty such accounts) but rather a practice’s propensity for violence, for curvature, for being exploited for the perpetuation of damage rather than received for its redress.” She writes in that way about Eucharist, prayer, and baptism “because I love them, and a lover wishes, in her rare mature moments, to know the truth of the object of her love, rather than to know only her wished-for, projected fantasy.”

After debuting with the unforgettable spiritual memoir Girl Meets God, historian Lauren Winner next wrote about the spiritual disciplines in Mudhouse Sabbath. But while that short book mostly celebrated the benefits of Jewish and Christian practices, Winner’s newest work warns of the dangers that can inhere to them. Starting with a survey of how supposed desecration of the Host led to anti-Semitic violence in medieval Europe and continuing with the prayers of slave-owning women, Winner considers “not primarily a practice’s propensity for fostering holiness (there are plenty such accounts) but rather a practice’s propensity for violence, for curvature, for being exploited for the perpetuation of damage rather than received for its redress.” She writes in that way about Eucharist, prayer, and baptism “because I love them, and a lover wishes, in her rare mature moments, to know the truth of the object of her love, rather than to know only her wished-for, projected fantasy.”

It’s not an easy read — a synthesis of theology, philosophy, and history rather than a spiritual memoir or devotional meditation — but worth pondering if, like me, you’re one of those Christians who thinks that what we do in following Jesus matters at least as much as what we believe. Winner is primarily responding to postliberal theology, but I found it interesting to read The Dangers of Christian Practice in light of some of Kristin’s posts about evangelicalism: to what extent are the more problematic (even “toxic”) aspects of evangelical Christianity “characteristic damages” of its practices, rather than incidental to them? (Chris)

Honorable Mentions: Lisa Bitel, Landscape with Two Saints: How Genovefa of Paris and Brigit of Kildare Built Christianity in Barbarian Europe (Oxford University Press, 2009); Michelle Obama, Becoming (Crown, 2018); Karen Swallow Prior, On Reading Well: Finding the Good Life Through Great Books (Brazos Press, 2018); April Vinding, Triptych (Wipf & Stock, 2016).