The most famous chain of events during what Americans came to call King Philip’s War began on February 10, 1676, when Nipmucs, Narragansetts, and Wampanoags attacked the Massachusetts town of Lancaster.

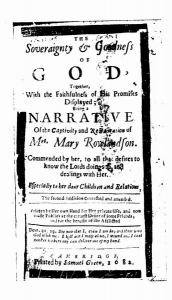

About fifty settlers were either killed or taken captive. Of the latter, Mary Rowlandson earned lasting renown with her autobiographical The Sovereignty and Goodness of God, published in 1682 some six years after her redemption.

Joseph Rowlandson, Lancaster’s minister, was in Boston at the time of the raid. When he returned, he found his town in ruins and his wife and three children missing. Rowlandson returned to Boston.

Joseph Rowlandson, Lancaster’s minister, was in Boston at the time of the raid. When he returned, he found his town in ruins and his wife and three children missing. Rowlandson returned to Boston.

A few months ago, I wrote about a sermon on the death of children delivered by Cotton Mather the very day of his daughter’s death. Joseph Rowlandson also preached in the middle hour of his grief.

Ten days after the raid, at Boston’s Old South church, he took as his text Deuteronomy 7:9: “Know therefore that the Lord thy God, he is God, the faithful God, which keepeth covenant and mercy with them that love him and keep his commandments to a thousand generations.

John Hull, a leading Boston merchant and the colony’s treasurer during the war, took copious notes on sermons, and the Massachusetts Historical Society holds several of his sermon notebooks. Hull recorded notes on hundreds of sermons. Collectively, they provide a wonderful glimpse into what Edmund Morgan called “the weekly Sunday diet of the average Puritan.” [See Morgan, “Light on the Puritans from John Hull’s Notebooks,” New England Quarterly 15 (March 1942): 95-101.] As Morgan noted, Hull also recorded several “espousal ceremony” sermons, which bound couples who intended to marry.

Among the hundreds of sermons is Joseph Rowlandson’s of February 20, 1676. Morgan excerpted some key sentences and phrases from Hull’s notes, and I am adding in some additional detail from the manuscript, leaving Hull’s spellings uncorrected but expanding his abbreviations. Hull’s notebooks are a wonderful source. His writing is easy to read, and even the “skeletal” (Morgan’s adjective) are very extensive. They are New England sermons refracted by Hull, and it is impossible without consulting other sources to gain any sense of how congregants received them. Still, at the very least they provide a very extensive window into the thought of Thomas Thacher (Old South’s minister during most of the years in question) and the many other New England ministers who preached there. I consulted the notebooks to track down a sermon delivered by Plymouth Colony’s John Cotton.

The context of Deuteronomy 7 is that will be faithful to a people that he has redeemed. When Rowlandson reminds the congregation that “the Israele of god will find it of great use to know that god is faithfull,” he and they presumed that the orthodox settlers of New England are God’s new Israel. He continued: “faithfulness in god is a glorious essintiale perfection whereby god is true to himselfe & to all that put their trust in him.”

As Morgan notes, Rowlandson proceeded by syllogisms and a passel of biblical quotation to prove God’s faithfulness. It probably took him a long time to talk through all of the passages.

Obviously, the faithfulness of God did not exempt his Israel from earthly trials. Far from it. He would sometimes deal “with them in a castigatory way.” Nevertheless, God remained bound to his people through covenant. “it is a bitter mercy,” Rowlandson allowed, “but it is a cove[na]nt mercy.” God is always faithful to his people, both when he brings about trials and when he removes them.

Therefore, Rowlandson contended, “those that have god for their god cannot be miserable such are happy that have god for their portion whatever evils you meet with.” God’s people should humble themselves “for any other thoughts that [they] have had of god.”

Rowlandson such wavering as sinful. They had not been faithful. They had been “unsteady” and “fickle.” Satan sought to undermine their trust in God’s faithfulness. They needed to repent. They needed to cleave to God and to “all his instituted worship.”

In the end, Rowlandson wanted to comfort rather than chastise. The doctrine of God’s faithfulness should be a consolation. God could not be anything other than faithful. “he may hide his face,” Rowlandson preached, “but he cannot goe away utterly from his [people].” “the creature fails,” he continued, “but the creatour fails not this may comfort ag[ain]st satans insultations.” Perhaps they felt that everything was presently too hard. “wait a while,” Rowlandson promised, “the lord will shoot at them [and the lord is he] who never missed his mark.”

Rowlandson urged the congregation to pray “that god will give [you] to experience this truth god is never at a stand.”

Unlike Cotton’s reference to his daughter’s death, as far as Hull’s notes reveal, Rowlandson never mentioned his own afflictions or those of New England more generally. In fact, there is no way to know that he chose his topic and theme after the raid. Rowlandson preached at Old South with some frequency; perhaps his prior sermon had taken Deuteronomy 7:8 as his text. Still, it seems reasonable to conclude that Rowlandson had present afflictions in mind.

When upbraiding those who were unsteady or fickle in their trust, did he have himself in mind? New England ministers were not all rock-solid paragons of faith. Boston’s Increase Mather, for instance, confided to his diary that he endured “Heavy temptations to Atheisme.” It is reasonable to presume that like many ministers, Rowlandson preached to himself.

He needed comfort. God would not fail. God would punish the wicked. God had hid his face for a time but would not leave his people.

Rowlandson did not mean that God would make everything work out for those who put their trust in him. He did not know if his wife and children would return to him. (One child died). Rather, God’s promise of protection was not “temporally” but rather “spiritually & eternally.” A hard truth, and not just in 1676. Still, God’s faithfulness would provide comfort and consolation. God was both sovereign and good.