A week from tonight, PBS will debut a Ken Burns-produced (though not directed) documentary about the Mayo Clinic, the world-famous medical center based in Rochester, Minnesota. Though religious themes are barely hinted at in the trailer, the film is subtitled Faith • Hope • Science.

That combination of words makes perfect sense to me: my rather devout dad just retired after a 45-year career as a world-class pediatrician and medical researcher and remains highly active in a Southern Baptist church. But on my Facebook feed, I’ve noticed the subtitle rubbing some people the wrong way. One doctor friend complained that placing faith and hope ahead of science was the medical equivalent of offering “thoughts and prayers.” Another commenter insisted that religious faith can only obstruct scientific progress.

But the actual history of medicine and religion, and of the Mayo Clinic, is much more complicated than that.

In his historical introduction to Medicine and Religion, Gary Ferngren rejects “the notion that there has existed throughout history an essential conflict between religion and science.” And while he documents examples of tension between religion and medicine, Ferngren notes that the two have often gone hand-in-hand, even in the modern era:

Even today the religious beliefs of many Westerners intersect with the culture of healing and health care in surprisingly traditional ways. These beliefs often lie under the radar of public or media perception and, when made public, may be ridiculed as hopelessly anachronistic. Yet a belief in God often quietly motivates a physician or health-care worker to provide compassionate care for those who are ill, or to help the sick endure pain and suffering, or to give spiritual consolation to the dying. Physicians and patients alike pray for divine help and healing, especially when they have exhausted all the avenues of modern science and medical knowledge. Faith today still offers the hope of some relief to many who experience chronic or untreatable diseases. And it provides a comfort that modern medicine and science do not: the belief that there is divine purpose in suffering, some meaning in all the pain one bears. Perhaps faith even holds a role in healing not altogether foreign to that of the ancient world, although modern men and women might take quite a few steps along their medical journey before realizing that they may have need of their faith before that journey is over.

Also the author of a study of the role of early Christianity in the development of medicine, Ferngren is particularly admiring in his attention to Catholic religious orders dedicated to medical care: “No element of Catholic philanthropy in America has been as impressive as the organization of medical care by nursing orders of nuns. The earliest nursing sisters offered mostly palliative care, but they were quick to learn new techniques, and the discipline of the orders provided good training for the founding and administration of hospitals and other medical institutions.” One of the most famous examples of this theme brings us to the story of the Mayo Clinic.

An English immigrant who came to Minnesota in the 1850s, Dr. William Worrall Mayo began practicing medicine in Rochester in 1863. But it was two decades later that what we think of as the Mayo Clinic came into being, after a devastating tornado hit the small town. Mayo treated victims with the assistance of his sons Will and Charles, as well as nuns from the Sisters of St. Francis. Their leader, Mother Alfred Moes, had a vision for a full-fledged hospital and approached the elder Dr. Mayo. Ferngren reports:

An Episcopalian, Dr. Mayo initially saw difficulties with the proposal, but Mother Alfred responded, “The cause of suffering humanity knows no religion or sex; the charity of the Sisters of St. Francis is as broad as their religion”… Under the determined leadership of Mother Alfred, the hospital grew to become the largest privately operated hospital in America.

With the services of Mayo and his sons, St. Mary’s Hospital opened in 1889. It remains a campus in the Mayo system to this day, its 55 operating rooms hosting tens of thousands of surgeries each year. (My wife worked in the orthopedic unit during her graduate training in occupational therapy.) I don’t want to make too much of the role of religion in its history, but Mayo continues to describe its values as “an expression of the vision and intent of our founders, the original Mayo physicians and the Sisters of Saint Francis.”

(Given that the Pauline virtue displaced by science in the documentary’s subtitle is love, it’s important to note that one Mayo core value is compassion, which Ferngren argues “is a quality fully compatible with scientific medicine and with progress in medical technology [but] not one that grows naturally out of either… without a transcendent and spiritual basis, it lacks the sustenance necessary to nurture and perfect it.”)

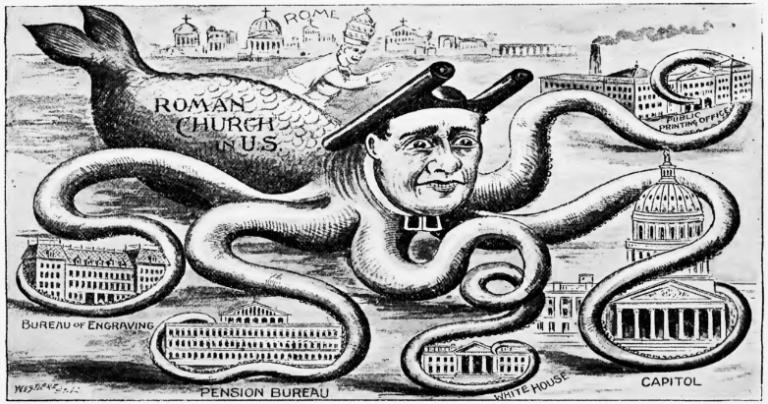

I assume that the story of Dr. Mayo, Mother Alfred, and St. Mary’s Hospital will feature prominently in the PBS documentary next week. But I’ll be curious to see if the filmmakers touch on an uglier dimension of that origin story. As Helen Clapesattle explains in her 1941 biography of Mayo and his sons, a partnership between Protestant doctors and Franciscan nuns raised the hackles of Midwestern nativists who saw “the bogey man of papal imperialism behind the door of every Catholic home and institution….”

An heir to some of the same impulses that fed the antebellum Know Nothing movement, the American Protective Association (APA) was founded by a Methodist lawyer and Freemason named Henry Francis Bowers in 1887. He and six friends in Clinton, Iowa — just over 200 miles south of Rochester — had concluded that “the institutions of our Government were controlled and the patronage was doled out by an ecclesiastical element under the direction and heavy hand of a foreign ecclesiastical potentate.” Within less than a decade — and with a set of new, much less secretive leaders — the APA claimed over 100,000 backers nationwide. The group also drew the attention of labor leader Eugene Debs; two months before the Pullman Strike, Debs thundered:

To call [the APA] “American” is to outrage all truth and decency. It is a blasphemous arraignment of the term “American,” which from the foundation of the government has been a standing rebuke of all religious intolerance…

…to make [“American”] play any part whatever in the damnable game of religious bigotry and persecution is infamous beyond the power of adequate characterization. It is the acme of devilishness. It is satanic without a redeeming qualification.

Nonetheless, the APA’s strength in Rochester had been sufficient to deter other physicians from joining the Mayos at St. Mary’s. “Ardent Protestants,” writes Clapesattle, “would have none of an institution that was managed by black-robed nuns and in which there was a chapel set aside for the exercise of popery….” In response, the elder Dr. Mayo recruited a superintendent who was a prominent Presbyterian but also “a man above fanaticism,” and tensions died down for a few years.

For their own part, the “Drs. Mayo did not share the sisters’ faith, but they did not scorn it.” Unable to heal one woman who came to St. Mary’s, Will Mayo told the attending nun, “I know she can’t live, but you burn the candles and I’ll pay for them.” (The patient survived.)

As the APA reached its national peak in 1894 — and even began to back anti-Catholic political candidates — a local homeopath tried to use nativism to his own advantage, setting up a new hospital as “an institution that Protestants and patriots could enter without doing outrage to their convictions by furthering an agency of the hated and alien Catholic church.” The Mayos declined to treat patients there, prompting condemnation from at least one Protestant pulpit, and instead focused their efforts entirely on the partnership with the Sisters of St. Francis. A year later, the homeopath returned to St. Paul, leading St. Mary’s onto a road that “lay smooth and straight, mountly with scarcely a level stretch or a detour to the heights of worldwide service and fame.”

For more on the role of Christians and churches in the history of medicine, see this 2011 issue of Christian History Magazine.