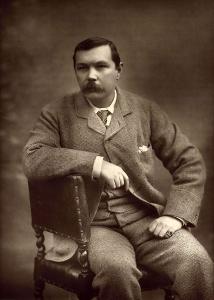

I’ve been waiting nearly three years for this day to come: when my regular turn in the Anxious Bench rotation coincides with the birthday of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, giving me a ready-made excuse to write about my favorite character in literature. Yes, the creator of Sherlock Holmes was born May 22, 1859.

So what does that have to do with the “relevance of religious history for today”?

Given the middle name Ignatius and educated at several Jesuit schools, Conan Doyle ultimately left the Catholicism of his parents — but he didn’t leave religion out of his most loved stories. Indeed, Holmes was introduced in a novel whose second half has almost nothing to do with Sherlock Holmes and everything to do with non-Mormon anxieties about the Latter-day Saints. Brigham Young himself appears to tell a convert that his daughter must marry a Mormon, setting in motion a plot that leads to her death and a quest for revenge ending in Holmes’ London. (See also Philip’s 2017 post, “American Violence: Things Fall Apart.”)

Of course, Conan Doyle is far better known for his embrace of Spiritualism, especially after his son’s death in World War I. As Philip notes in his religious history of that war, Conan Doyle published The New Revelation in 1918, describing Spiritualism as “the very essence of religion… the great unifying force, the one provable thing connected with every religion, Christian or non-Christian, forming the common solid basis upon which each raises, if it must needs raise, that separate system which appeals to the varied types of mind.”

But he was particularly hopeful that “the light which we get from the spirit” would reform Christianity, which he thought “must change or must perish… Christianity has deferred the change very long, she has deferred it until her churches are half empty, until women are her chief supporters, and until both the learned part of the community on one side, and the poorest class on the other, both in town and country, are largely alienated from her.” In particular, he hoped to see less attention paid to the Crucifixion:

It is no uncommon thing to die for an idea. Every religion has equally had its martyrs. Men die continually for their convictions. Thousands of our lads are doing it at this instant in France. Therefore the death of Christ, beautiful as it is in the Gospel narrative, has seemed to assume an undue importance, as though it were an isolated phenomenon for a man to die in pursuit of a reform. In my opinion, far too much stress has been laid upon Christ’s death, and far too little upon His life. That was where the true grandeur and the true lesson lay.

Ultimately, Conan Doyle concluded that the Early Church had lost sight of Christ’s life and teachings in its obsession with “a conquest over death [that has], as it seems to me, little meaning in the present Christian philosophy, whereas for those who have seen, however dimly, through the veil, and touched, however slightly, the outstretched hands beyond, death has indeed been conquered.”

Of course, the coldly logical Holmes would seem like a natural skeptic of the “psychical knowledge” for which his creator evangelized. The Scarlet Claw, the best of the World War II-era films made by Universal, finds Holmes and Watson attending a meeting of an occult society in Canada. “If the facts are there,” insists a Conan Doyle-like aristocrat, “even the most hardened skeptic — provided he has an open mind — must finally acknowledge the actual existence of the supernatural.” “Facts are always convincing,” responds Basil Rathbone’s Holmes. “It’s the conclusions drawn from facts that are frequently in error.” Later characterizations have made the detective even more dismissive of anything like religious or spiritual belief. In a memorable toast at John Watson’s wedding, Benedict Cumberbatch’s Sherlock dismisses God as “a ludicrous fantasy designed” — he says, looking at the vicar — ”to provide a career opportunity for the family idiot.”

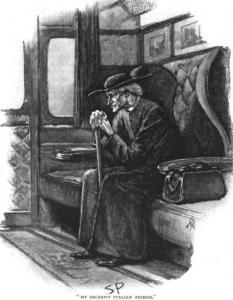

Nevertheless, the original Sherlock Holmes twice disguises himself as a man of the cloth: “an amiable and simple-minded Nonconformist clergyman” as he tries to head off “A Scandal in Bohemia,” and “a venerable Italian priest” in escaping Professor Moriarty during “The Final Problem.” (Holmes later conducted a special investigation at the request of the pope himself.) He quotes or paraphrases Scripture on several occasions, and discusses both Buddhism and miracle plays in the midst of Conan Doyle’s second Holmes novel, The Sign of Four.

Details like these became fodder for Holmes enthusiasts who approached what they called “The Canon” with something like the Higher Criticism Philip has been blogging about of late. Since its founding after World War II The Baker Street Journal has published several articles on religion. Leading the way in 1948 was Edgar S. Rosenberger, who furnished some of the details cited above and concluded that Holmes was genuinely (albeit unpredictably) religious:

Again and again throughout the tales we see Holmes the philosopher, Holmes the theologian, Holmes the humble minister of the gospel. Even as the prophets of old, he pondered the infinite mysteries of life, and sought an answer…. His real desire was to be a minister of the gospel. His penchant for sermonizing, his fawning servility toward the clergy, his irrepressible urge to masquerade as one of them, point to no other conclusion.

Rosenberger did not try to define Holmes’ religious affiliation. Some Sherlockians have suspected that he was Catholic or Jewish, while Holmes “biographer” William S. Baring-Gould (grandson of the Anglican priest who wrote “Onward, Christian Soldiers”) argued that Holmes embraced Buddhism during his time in Tibet. In his 1965 review essay on the subject, Rev. Henry Folsom concluded that Sherlock Holmes was at least a nominal Anglican (he tells us in passing that he attended chapel while he was at college), but “almost certainly a child of that strange Victorian age, a sentimental age, but one in which intellectuals very often drifted far away from orthodox religion and settled into a certain reverent agnosticism.”

Folsom himself was an Episcopal priest, and it’s also worth noting that two of the most famous British Christian writers of the 20th century were Sherlockian scholars. Dorothy Sayers tried to reconcile the “curious chronological problems” of “The Red-Headed League” in a 1934 essay. (Her version of Sherlock Holmes solved one mystery by recognizing a crossword puzzle’s allusion to the Song of Solomon — in the Vulgate!) Then G.K. Chesterton not only fulfilled Rosenberger’s wish by letting his version of Holmes both solve crimes and preach homilies, but in 1935 critiqued the critical methods being applied to this canon:

These books are not only solemn but solid. They are, like very learned reports on purely scientific questions, almost avowedly dull. They also may be written for fun; but they are not funny. They cross-examine poor Watson about every detail of date and weather and topography and time-table, like hanging judges investigating a real murder. They refute him with tables of figures no more amusing than columns in a ledger. They may not really regard it as real history, but they take as much trouble as the greatest scholar would take about real history, unrewarded by a smile. It may be a grim joke; but it is the sort of joke that conceals the joke. The hobby is hardening into a delusion. Not once is there a glance at the human and hasty way in which the stories were written; not once even an admission that they ever were written. The real inference is that Sherlock Holmes really existed and that Conan Doyle never existed. If posterity only reads these latter books, it will certainly suppose them to be serious. It will imagine that Sherlock Holmes was a man. But he was not; he was only a god.