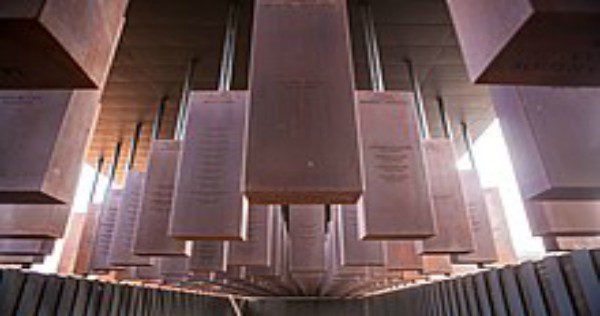

On April 26, the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, in Montgomery, Alabama, opened its doors. The memorial is visually stunning. Around 800 rusted iron columns hang from above, each representing a county where a lynching took place. In a recent essay in Religion News Service, Jemar Tisby recounts just a few of the horrors that the memorial represents:

“The memorial reminds visitors that lynching victims are real people, not simply anonymous figures from history. They have heart-wrenching stories such as Luther Holbert who was forced to watch as a white mob burned his wife, Mary, alive before they killed him. Others lynched Elizabeth Lawrence for telling white children not to throw rocks at black children. Lynchers killed Mary Turner, eight months pregnant, for protesting the lynching of her own husband, Hazel Turner. The voyeuristic and violent deaths of these individuals plus thousands more represent the heinous apotheosis of American racism.”

Not all Americans are thrilled with this new memorial to the African American past (which also, of course, memorializes a white American past). “It’s going to cause an uproar and open old wounds,” remarked a 58-year old Montgomery woman interviewed by The Guardian, who claimed that locals feel “it’s a waste of money, a waste of space and it’s bringing up bullshit.” Other white residents feared the memorial might incite violence. As one man, a member of the Alabama Sons of Confederate Veterans put it: “We have moved past it…You don’t want to entice them and feed any fuel to the fire.” Many white residents, it seems, would prefer to “Let sleeping dogs lie.”

Fifty years ago, historian and civil rights activists Vincent Harding reflected on precisely this question. Writing in motive magazine, the magazine of the Student Christian Movement, in April of 1968—the month of Martin Luther King Jr’s assassination—Harding reflected on the importance of knowing “The Afro-American Past.”

At that time, very little black history tended to be included as part of the American story. Only small doses could be tolerated, Harding claimed, “For if they are too many and too black, these encroachments might necessitate unpleasant rereadings, reassessments and rewritings of the entire story.”

But according to Harding, “An American history which cannot contain the full story of the black pilgrimage is no more worthy than an American society that cannot bear the full and troublesome black presence in its midst.” American history must incorporate the African American experience “with unflinching integrity.” If it does not, it amounts to “a tale told by fools.”

The history of the Constitution, of slavery, of Reconstruction, of national expansion, of urban unrest—this history must be written with attention to the lives of black people. And, Harding added, “If such open encounter between black and white history should produce the same insecurity as we now experience in the human encounter, so much the better.”

Why was it so critical to tell the story of the African American past? For one thing, “A history without the Afro-American story may indicate why this nation can now be so numb to the brutalization of a Vietnam thousands of miles away,” Harding suggested. “In denying the physical and spiritual destruction of black persons which has become a part of the American Way of Life, a callus has grown on whatever heart a nation has.”

Such a history, he reflected, “has contributed immensely to the miseducation of the American people and has not prepared them to face a world that is neither white, Christian, capitalist, nor affluent.” And such history, Harding warned, “may yet prove poisonous.” But if there was an antidote to this poison, “it could be the hard and bitter medicine of the Afro-American past.”

“Is it too late for a society that still insists that its drops be few and painless?” Harding wondered, back in 1968.

Teaching the African American experience was not “teaching hatred of whites,” he clarified. “Rather it is the necessary and healthy explanation for the existence of the hatred and fear that most black men have known from childhood on. Any society lacking the courage to take such risks with light lacks the courage to live.”

Drawing on A. J. Muste and W. E. B. DuBois, Harding drew a distinction between “those people who had rarely if ever known defeat and humiliation as a national experience and those who had lived with this for centuries.” The majority of those who have known humiliation have been non-white, and “their humiliation has come at the hands of the white, Western world”; America stood as “the self-proclaimed leader of that unhumiliated world.” In this way, America was blind when it came to understanding the oppressed. This ignorance was especially dangerous when combined with “the American predilection towards violence” and “the American stockpile of weapons,” Harding noted.

Yet Americans were caught up in a romantic myth of their own innocence: “Ever since the nation’s beginning it has been plagued by this…crippling misconception of itself.” But in failing to face the tragic, America failed to mature. If historians and citizens alike were to face the reality of the African American past, “many—if not all—of their liberal, superficial myths about, and hopes for, American society might be transformed.”

But to do so, they would need to rethink their old heroes.

And they would need to do away with notions of American exceptionalism: “The black experience in America allows for no illusions, not even that last, ancient hope of the chosen American people whom God will somehow rescue by a special act of his grace.” Perhaps the real lessen to be learned, Harding mused, was that only black people, by virtue of their suffering, were poised “to lead this nation into true community with the non-white humiliated world.”

In recent weeks, a study by sociologists Andrew Whitehead, Joseph Baker, and Samuel Perry has revealed the significance of Christian nationalism in solidifying Christian support behind Trump—the idea that America is fundamentally a Christian nation. This should come as no surprise. From the 1960s on, conflicting views on whether America is indeed a “Christian nation” have divided the nation’s Christians, and driven its religious and political polarization.

If Harding is right, the African American past may hold the key to depolarizing American faith, and politics. Drawing attention to this past is no small feat, particularly within Christian nationalist strongholds. But if this is indeed a way forward, Montgomery’s National Memorial for Peace and Justice is poised to play a critical role in this endeavor.

As Harding reminded us, “There will be no new beginnings for a nation that refuses to acknowledge its real past.”