In July 1925, America was gripped by a spectacle of the sort that reality TV would later perfect. The small hamlet of Dayton, Tennessee hosted a trivial court case that town leaders puffed into a media circus. The contest was whether evolution should be taught in public schools.

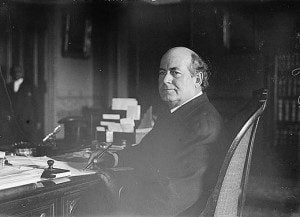

At the prosecutors’ table sat the one-time Democratic (and Populist) presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan—defender of the common-man. On defense sat the urbane Charles Darrow, a brilliant attorney known for taking morally ambiguous cases.

There was no Court TV in the 1920s, but America did have H. L. Mencken: an acerbic, bigoted, whiskey-swilling journalist with a gift for words. His courtroom reporting from Dayton mercilessly ripped into the aging Bryan as a “pathetic fool” and “a tinpot pope.” When he wandered outside the courthouse, his reporting shifted to mocking travelogue. Recounting an outdoor prayer service, he described a “not uncomely” woman, “buried three deep” under an “obscene heap” of sweaty, tongues-speaking intercessors. “How she breathed down there I don’t know,” he dryly noted, since “it was hard enough ten feet away, with a strong five-cent cigar to help.” He affixed the label “fundamentalist” to both Bryan and these “Holy Rollers.” Both, Mencken claimed, were the result of making “the Bible…the beginning and end of wisdom.”

No event looms larger in the history of fundamentalism than the Scopes trial, despite the research suggesting this attention is unwarranted. Edward Larson’s Pulitzer-Prize-winning narrative demonstrated no leading fundamentalist participated in the trial. Matthew Sutton has convincing challenged the claim that Scopes led fundamentalists to “withdraw from culture.” It seems the event is just too dramatic to ignore, even though we know that, like The Real Housewives franchise, much of its drama was manufactured.

If we’re stuck with Scopes, let’s use it to crack open an even more troubling historical fiction: that we can treat “fundamentalists” (the short-lived label for conservative evangelicals in the 1920s) as a unified group. We want our evangelicals to share a basic theology, or a set of practices, or a political persuasion, or an overarching “worldview” that remains constant across other social and cultural divides. And so we hop from one event (the publication of The Fundamentals) to another (the Scopes trial) to explain how the “movement changed.” But in reality we are simply jumping from one group to another without reference to the chasm that divided them.

In previous posts, I have focused primary on one strand of evangelicalism, the corporate evangelicals: that network of businessmen and other respectable Protestants surrounding Dwight L. Moody who controlled the major fundamentalist institutions of the early twentieth century. I have explained how they understood their faith though economic metaphors and modeled their practices on corporate strategies.

But to really understand the significance of the Scopes trial—and to understand the challenges to corporate evangelicalism both then and today—we need to examine other evangelical groups as well. Who were the “other” evangelicals? How did these groups develop and interact with corporate evangelicals? What alternative models did they use to understand their individualistic faith and how did their social context influence their belief and practice?

***

For every Phoebe Palmer spreading evangelical tenets in middle-class parlors, there were scores more worshiping as they always had in raucous campgrounds and clapboard churches. Adherents hailed from many sects and had distinctive beliefs and practices, but for simplicity’s sake I will refer to them as “plainfolk evangelicals.”

Corporate evangelicals were clustered in urban and suburban areas; plainfolk evangelicals were scattered across the rural landscape. They were especially prominent in the South and West and among the white yeoman classes. You could find them in the northern plains and Great Lakes regions as well, but they were intermingled with substantial populations (Catholic and Protestant) who maintained strong churchly traditions.

Middle-class respectability was the central concern of corporate evangelicals—it was a badge of orthodoxy. In contrast, the preoccupation of plainfolk evangelicals was authenticity. This involved following the Spirit’s leading, including the exuberant worship styles and disruptive physical manifestations that corporate evangelicals rejected. They saw themselves as “respectable” in their own way, but this stemmed from moral uprightness, not social performance. To be socially respectable was to flirt with compromise, pleasing “man rather than God.” It was exchanging the mess of porridge that was elite acceptance for their birthright as children of God.

Class position of plainfolk evangelicals ranged from poor sharecroppers and laborers to craftsman and small shop owner (the “petite bourgeoisie”) to the many small farmers in-between. Some went to work in northern factories and helped spur the Social Gospel movement; others fought for worker’s rights in the new cotton South.

Like most yeomen followers of Jefferson and Jackson plainfolk evangelicals were Democratic in politics, though many joined the Populist party in the 1890s. Not surprisingly, William Jennings Bryan drew much of his support from these evangelicals. (And looking ahead, it was the same group who migrated to California in the 1930s and 40s.) Corporate evangelicals, in contrast, were nearly all Republicans on friendly terms with industrialists. Like most in his circle, the revivalist Dwight Moody feared that the election of Bryan would spell the end of American civilization.

Yet it was not just the content of politics that divided plainfolk evangelicals from their corporate kin, it was also the centrality of political and legal categories to understanding their faith and shaping their practice.

An economic model understood salvation primarily as an act of free exchange between God and the individual believer. The political model focused on obligation. God expected obedience and promised protection. Thus corporate evangelicals tended to see the unsaved as potential clients who needed to be sweet-talked into salvation. They saw themselves as part of the divine sales force.

Plainfolk evangelicals, in contrast, understood themselves to be God’s political operatives, warning uncommitted souls of the consequences to remaining on the wrong side of the spiritual conflict. The unsaved were lawbreakers needing discipline; God was a divine police officer, knocking heads to maintain order.

Corporate evangelicals saw salvation offering the convert a new opportunity; plainfolk evangelicals saw salvation as God’s offer of protection—both from divine judgment and the devil’s attacks.

We should not overstate the differences here; legal and economic models were not mutually exclusive. It was a matter of emphasis—of primary identification.

But these differing emphases mattered. For example, economic models led adherents to see salvation as God freeing the believer from “the Law.” It was the cutting of spiritual red tape so that they could work more efficiently. Those rooted in legal models gravitated toward seeing salvation as empowering the individual believer to fulfill the just requirements of “the Law.” One could read the Bible to support either claim.

At the turn of the twentieth century, both groups had similar lists of do’s and don’ts pertaining to social and cultural life. But those who were economically oriented framed these rules as the means to other ends (typically to maintain their respectability or to keep their personal relationship with God in good condition). Those leaning toward legal models treated the rules as ends in themselves; rule-keeping was evidence that one’s faith was authentic. Economic models allowed for much greater flexibility for adapting the latest cultural trends. Legal models tended to consider those innovations “worldly” compromise. If you are an evangelical who has a tattoo or drinks beer or plays cards or attends any sort of theater, you have economic models of salvation to thank.

A final key difference between these evangelicals related to their primary mode of social engagement. Corporate evangelicals’ libertarian tendencies led to an almost exclusive focus on evangelism. There were exceptions carved out for moral legislation against sexual vice and half-hearted support for Prohibition. But they were more likely to claim that you could not legislate morality; transformation came by converting individuals. Plainfolk evangelicals, in contrast, saw promoting moral legislation as part and parcel of their reform agenda. Just as God promised protection, so they were obliged to protect society from moral contagion.

***

If economic and legal models found their beginnings among corporate and plainfolk evangelicals respectively, there was considerable cross-fertilization in the 1880s and 1890s. Both models were transformed in their new social and cultural contexts.

The primary carrier of corporate ideas into plainfolk circles was Moody, one of the few figures to cross the evangelical divide. Notwithstanding his elite friends and preoccupation with middle-class decorum, his homespun wisdom and grammatical errors assured plainfolk evangelicals he was keeping it real. But where Moody saw his ideas supporting the new corporate order, working class and populist evangelicals used these same ideas to challenge it.

The end result was a new type of evangelicalism called Pentecostalism that emerged in the early twentieth century. The movement combined corporate evangelical ideas with streams of plainfolk holiness, African American evangelicalism (a rich and important topic I will leave for another post), and a heady conviction of the imminent physical second coming of Jesus. Pentecostalism first gained attention in Los Angeles and quickly spread around the world to places both urban and rural. It was often interracial, encouraged women’s equal participation in leadership, and was utterly terrifying to respectable Protestants.

Corporate evangelicals and Pentecostals shared many core assumptions about the relationship between God and humanity. But the implications were diametrically opposed. For example, both corporate evangelicals and Pentecostals understood their Bible to be a contract between the individual believer (a Christian worker) and God (the divine employer). Both believed God was capable of miraculous intervention in the physical world. But corporate evangelicals insisted that believers must also fend for themselves, trust the wisdom of God (as they wanted workers to trust their managers), and that they must submit to professional authorities—medical professionals for matters related to the body, accountants and lawyers for balancing books and filing legal papers.

Working class Pentecostals, in contrast, were used to fighting with the owners of capital to get their due. Thus, they had no qualms about making demands of God—to “name and claim” a miracle because it was promised in the Bible. Populist evangelicals, negatively impacted by professionalization, used these same assumptions to challenge the authority of the professional classes. True believers with authentic faith must trust God alone for their health, they insisted, rather than questionable chemicals and human wisdom. Faith ministries must resist professional fundraising and modern accounting; organizations should close their ears to the siren song of professional management.

Ironically, corporate evangelicals battled the Pentecostal insurgency with tools that were initially popularized in plainfolk circles. This too was a complex set of exchanges, but the end result was that corporate evangelicals widely adopted an interpretive system called dispensationalism. It was initially popularized by upwardly-mobile men of plainfolk origins. The most important was Cyrus I. Scofield, who became a close associate of Moody in the 1890s. A lawyer by training, he unabashedly applied similar techniques to Biblical interpretation. He also used the sophisticated compartmentalization of texts according to the time (or “dispensation”) for which he deemed they were intended. This effectively limited God’s liability for certain biblical promises like miraculous healing or speaking in tongues (a central evidence Pentecostals claimed for Holy Spirit power).

The scientific certitude that dispensationalism promised had a tendency to encourage belligerency in adherents with plainfolk roots. But this was tempered by the corporate evangelical conviction that honey caught more souls than vinegar.

***

Thus the intensive cross-fertilization between plainfolk and corporate evangelicals, the flouting of racial and gender mores by early Pentecostalism, and the perceived dangers of Protestant liberalism led to a wholesale dissolution of traditional Protestant divides in the 1910s. It was then that corporate evangelicals published The Fundamentals, marking the beginning of the movement.

As I explain in my book, the publication never effectively fulfilled its promise to create doctrinal basis for a new interdenominational conservative Protestantism. Instead it created an imagined community of those committed to the idea of conservative Protestantism—even though no one could define it with any precision. Because a fundamentalist identity was created primarily by stating what it was not, individuals filled in the blanks for themselves. It effectively united an impossibly-diverse group of “conservatives” under the label “fundamentalist” that never really existed.

Corporate evangelicals took the lead in formally organizing the fundamentalist movement through a series of meetings and conferences that ultimately resulted in the World’s Christian Fundamentals Association (WCFA). But almost immediately it was overtaken by a legal-oriented leadership often with plainfolk roots, men like William B. Riley. In the early 1920s corporate evangelicals were bitterly complaining that these men were destroying the movement. They quietly extricated themselves from the WCFA and even began distancing themselves from the “fundamentalist” label they helped create.

By the time of the Scopes trial, the fundamentalist movement had become hopelessly fractured. Corporate evangelicals were no fans of evolutionary theory, but warned against attempting to outlaw its teaching. And they had little more appreciation for Bryan than they had exhibited thirty years before. They had spent nearly twenty years battling the exuberant forms of worship that Mencken witnessed—and no doubt exaggerated in his reporting. It was not simply that corporate evangelicals never showed up at Dayton, they wanted absolutely nothing to do with it. They knew a promotional boondoggle when they saw it.

We take as gospel today that Bryan and the other interested parties in Dayton were “fundamentalists” largely because of Mencken’s colorful reporting. But these figures had no substantial connections to the people who produced the Fundamentals, published the leading fundamentalist journals, or operated the leading Bible Institutes that first brought the fundamentalist movement into being.

Nor was Mencken a disinterested party. In fact, his other reporting suggests that his real targets were respectable evangelical busybodies in Baltimore. Among these was the staid Episcopalian Dr. Howard A. Kelly, a respected professor of obstetrics at Johns Hopkins, a leading advocate for Sabbath-keeping, and a contributor to The Fundamentals. At one point Mencken recommended Dr. Kelly spend a summer in Dayton, after which “he will return to Baltimore yelling for a carboy of pilsner and eager to master the saxophone. His soul perhaps will be lost, but he will be a merry and a happy man.” By using a broad fundamentalist brush, Mencken could attack the respectability, and thus the social authority, of troublesome opponents closer to home.

Mencken’s tactic worked stunningly well. Corporate evangelicals found themselves painted in a corner, unable to distinguish themselves from their uncouth country cousins, overbearing pugilist allies, and class-conscious zealots. And with the onset of the Great Depression a few years later, the entire corporate evangelical edifice seemed to teeter on the edge of collapse.

The “other evangelicals” were thus central in thwarting corporate evangelicals’ vision to remake a personal faith for the respectable middle classes. But they were not the only hurdle. We will discuss those other impediments, and the ways corporate evangelicals eventually overcame them, next time.