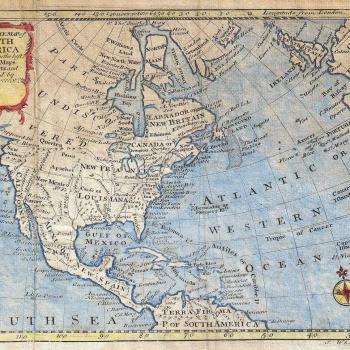

I have been comparing the decline of two once mighty religious systems, namely Buddhism in India, and Christianity in the Middle East. By the late Middle Ages, both were damaged irreparably, and had shrunk to shadows of their former selves. Indian Buddhism came close to extinction.

Both the Christian and Buddhist stories raise the fundamental question of how a particular religious system fits into a given territory, provided that it is not an established part of the state mechanism (and that is a major distinction). What would it mean to say that Iraq was mainly Christian at any point, or India mainly Buddhist? In Mesopotamia in 600, for instance, Christianity was a very widespread religion with a strong institutional structure, but it had no monopoly, and there was strong competition from Zoroastrians and Jews (and shortly, Muslims). We might be misled by the abundant Christian sources from these eras, which show only that Christian life was proceeding vigorously in monasteries and churches, with no necessary implication that the religion held any hegemony over the people, still less a monopoly. It is easy to be deceived by the volume and quality of our historical sources.

In India, similarly, the fact that monasteries flourished as they did meant that they must have received support and patronage from neighboring communities, but that does not imply that many or all of the local population espoused Buddhism at the expense of all other creeds. That is a crucial distinction with the West, in that joining or leaving Buddhism was never as formal or decisive a move as shifting between Christianity and Islam, or indeed Judaism. That difference in boundaries is, and always has been, one of the key markers separating Western and Asian religions. Christian monks noted grimly when their faithful laity defected to Islam. Their Buddhist equivalents might not have noticed such changes in popular support or loyalty.

Even Indian regions that were producing so much cutting edge spiritual literature were not necessarily Buddhist in any deep sense. And even in areas rich in Buddhist monasteries, much popular religious life might have carried on as it always had, following practices that were generally “Hindu.”

I recently read Lars Fogelin’s book An Archaeological History of Indian Buddhism (Oxford University Press, 2015), and I think this offers valuable analogies for understanding Western Christian history. Using an interdisciplinary approach, but primarily drawing on archaeology, Fogelin traces the history of Buddhism from roughly 600 BC through 1400 AD. Critically, he focuses on the dual themes of Buddhist monks and nuns, the sangha, and especially their relationship with their lay followers. Monks and nuns wanted to focus on individual mysticism and asceticism, which normally meant living in enclosed communities away form the world. At the same time, they had to operate within the larger Buddhist world, and work with laity. Those two dynamics often clashed. If monks and nuns withdrew entirely into the cloister, lay followers easily fell away.

Let me quote the book’s blurb here – and as you read it, you might be struck by analogies from the medieval Christian world:

Before the early 1st millennium CE, the sangha relied heavily on the patronage of kings, guilds, and ordinary Buddhists to support themselves. During this period, the sangha emphasized the communal elements of Buddhism as they sought to establish themselves as the leaders of a coherent religious order. By the mid-1st millennium CE, Buddhist monasteries had become powerful political and economic institutions with extensive landholdings and wealth. This new economic self-sufficiency allowed the sangha to limit their day-to-day interaction with the laity and begin to more fully satisfy their ascetic desires for the first time. This withdrawal from regular interaction with the laity led to the collapse of Buddhism in India in the early-to-mid 2nd millennium CE.

That last sentence is too stark for my taste, as it perhaps underplays the other trends and pressures under way in those centuries, including the rise of very militant Hindu regimes, but Fogelin makes some excellent points. His chapter headings include the following

Chapter 5 – The Beginnings of Mahayana Buddhism, Buddha Images, and Monastic Isolation: c. 100 – 600 CE

Chapter 6 – Lay Buddhism and Religious Syncretism in the First Millennium CE

Chapter 7 – The Consolidation and Collapse of Monastic Buddhism: c. 600 – 1400 CE

Monasteries withered as they lost their lay support, which defected to other newer faiths. That model works well in India, and it is a suggestive way of looking at at least some parts of the Middle East. So what were monasteries actually for? Contemplation alone? Or leading and mobilizing the Christian faithful?

But not all parts of that once-Christian region. Let me offer an exception that proves the rule (insofar as I understand what that phrase actually means). Egyptian Christians had a rich monastic presence, but in that case the faith was deeply embedded in the landscape, in villages and towns. When monasteries were sacked and persecutions happened, Christianity revived from those roots. Even today, after 1400 years of Islamic rule, perhaps 8 or 10 percent of Egyptians are still Christian, an amazing story of endurance.

In contrast, I wonder if Christians had anything like that embedded presence in territories like Central Asia, or if Buddhists did in much of India. And in each case, whether the critical factor in decline was the shift of those “roots” to another faith, long before the sensational acts of destruction or persecution.

Or as the famous phrase has it, the revolution took place in the hearts and minds of the people before any actual violence occurred.