I have been posting about the shifting boundaries of the Jewish world during the Second Temple era, and of Jewish political power. By the start of the Common Era, the Herodian family definitely ruled on behalf of the Roman Empire, but the territories in which they operated were far more diverse, ethnically and religiously, than we might think from a casual reading of the New Testament. Yes, Jews were widespread throughout the Roman Empire, and beyond. But if we just look at Palestine and its environs, there was a striking range of non-Jewish communities.

That diversity is multiply important. It suggests the diverse markets that existed for different movements within Judaism, and on its fringes. Such diversity surely contributed to religious creativity and innovation, and also, perhaps, to heterodoxy. It also laid the foundation for inter-communal conflicts that could, on occasions, provoke savage violence.

If we take the century or so between 50 BC and 50 AD, who are the occupants of these lands? The Jews are there, obviously, but so are the Samaritans, who occupy a substantial portion of Greater Palestine. But the Jews of the era were by no means a simple category. Most certainly were the descendants of ancient tribes, but there were also newer converts. Hasmonean rulers like John Hyrcanus not only conquered neighboring lands like Idumea (Edom), but demanded conversion. As Josephus writes,

Hyrcanus took also Dora and Marissa, cities of Idumea, and subdued all the Idumeans; and permitted them to stay in that country, if they would circumcise their genitals, and make use of the laws of the Jews; and they were so desirous of living in the country of their forefathers, that they submitted to the use of circumcision,and of the rest of the Jewish ways of living; at which time therefore this befell them, that they were hereafter no other than Jews.

There is no suggestion that these or other occupied peoples abandoned their new identity when Hasmonean power collapsed, nor that their Judaism was less devout than that of older-stock believers. But the experience does point to the likelihood of cultural hybridization.

One of those forced Idumean converts was Antipater, who married a Nabatean woman. Their child was Herod the Great, born in 74 BC, and was therefore of mixed ethnic and religious background. Perhaps only someone with those dubious credentials would have been so fanatically determined to prove his authenticity by rebuilding the Temple on that phenomenal scale. Little less effort went into seeking to prove that, all appearances to the contrary, Herod really did have ancient Jewish ancestry.

The territory also had substantial Gentile populations, some of ancient standing. Others, though, had been deliberately settled by successive Hellenistic regimes under a policy dating back to Alexander the Great. Greek kings settled veterans in new lands as a means of establishing centers of loyalty among alien and potentially restive populations. More positively, those cities helped spread Hellenization, and served as cultural magnates for native peoples. By all accounts, they worked very well in their cultural mission, if less so in the political realm.

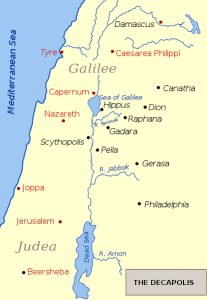

One critical example was the Decapolis, the group of Greek-founded cities to the east of the Sea of Galilee, and which receives several mentions in the gospels. Although the list officially includes ten cities, several others in the region certainly belonged. The best-known include Philadelphia (modern Amman), Gadara, Pella and Gerasa, while the somewhat more distant Damascus was loosely affiliated. The cities emerged under the Seleucid or Ptolemaic Empires, and several officially bore such characteristic imperial-linked names as Seleucia and Antiochia. And of course they were Gentile. It’s because he is in the Gerasene country that Jesus can find a herd of pigs to send demons to possess, after he has exorcised them (Mark 5).

(Image used under Creative Commons licence).

Apart from the Decapolis, there were plenty of other Greek centers that were favored and developed by the Herodian dynasty and the Romans. Sepphoris, near Nazareth, was one such, and the coastal regions retained that non-Jewish identity. Those cities, like Sepphoris itself, developed a strong Hellenistic/Roman identity, with the usual roster of theaters, temples and bath-houses. And of course, there were also synagogues.

You get some sense of this wider Jewish-based world from the fate of Herod’s family. Herod died in 4BC, and his sizable dominions (Map here) were partitioned among his sons, the Tetrarchs. Looking at the map of their possessions, we might think that the Jews had maintained and expanded their empire from Hasmonean days, but of course they had not. The Romans had no interest in identifying any one ruler with the Jewish people, if only to prevent him becoming a national leader, and they freely placed both Jews and gentiles under various members of the family. Even so, the map of where Herodian power expanded does give some sense of the wider sphere of influence extending beyond Jerusalem. And the fact that many Gentiles were brought into this political arrangement did have the unintended consequence of bringing them into close interaction with Jewish politics and society.

With that in mind, look at the map in more detail. The family history is complex (to say the least, allowing for murders and assassinations) but roughly:

*Archelaus received the heart of the ancient kingdom, with Judea, Samaria and Idumea. When he died in 6 AD, that territory became the Roman province of Judea.

*Herod Antipas received Galilee and Perea, the land immediately east of the Jordan.

*Philip was given Batanea, Trachonitis, Auranitis and various territories in what we would call the south and west of modern-day Syria. This also included Gaulanitis, a name familiar in modern politics as the Golan Heights.

If we combine those regions as an imaginary nation called Herodia, then it would have included most of the modern state of Israel, with major portions of Jordan, Syria and Lebanon.

The main exception, as always, is the Decapolis, the yellow portion of this map, which retained its independence from Herodian rule.

It’s difficult to convey to a modern Westerner just how very strong, if not impermeable, were the boundaries separating communities just a few miles apart, literally an hour or so’s easy walk. Yet however accessible one place might be from another – Nazareth from Sepphoris, say – the de facto walls were very high, dividing people by language, dress, custom, faith, and (above all) the mode of eating and drinking. It’s not easy to imagine a pleasant tourist visit to a city where everything you see around you constitutes an abomination to all you know and believe.

Palestine in this era was a patchwork of these micro-cultures, which survived by ignoring each other’s existence as much as possible. Sepphoris, to take an example, is never once referenced in the Bible. When we read the New Testament, we have to be constantly alert to the moments where Jesus is crossing these symbolic boundaries between regions separated by so little, and so very much.

Yet if some were appalled, others were attracted. Lawrence Schiffman, for instance, notes that “Those Jews who were interested in a higher degree of Hellenization … gravitated to the Greek cities, mostly on the seacoast and in the area to the east known in Roman times as the Decapolis” (From Text to Tradition, 71).

I’ll return to these issues.

Some books on these topics include Iain Browning, Jerash and the Decapolis (Chatto & Windus, 1982); Zeev Weiss, The Sepphoris Synagogue (Israel Exploration Society, 2005); David Kennedy, Gerasa and the Decapolis (Duckworth, 2007).