Gerard Russell’s Heirs to Forgotten Kingdoms is a remarkable book, both for its breadth and vision. Russell, a former British diplomat (who claims on the book’s jacket to speak fluent Arabic and Dari but within the book’s pages speaks a little bit of nearly every Middle Eastern language) surveys seven religions that are not only forgotten but vanishing, at least within their native lands.

Survey isn’t really the right word. Russell takes his readers to remote villages, sacred festivals, and obscure languages. Sometimes he hits roadblocks. The Druze will hardly ever reveal any of their mysteries. But without embarking on extensive (and risky) travel, Heirs to Forgotten Kingdoms is the closest most of us will come to these faiths’ ancient homelands.

The Samaritans are the smallest of the seven groups. Russell estimates that around 750 Samaritans still live, in one village on the top of their sacred Mount Gerizim and on one street in Tel Aviv. Actually, things may be looking up. Russell informs that in the 1940s there were only two hundred Samaritans.

The Samaritans (those responsible for the good Samaritan and the woman at the well in the New Testament) are the descendants of the ten northern tribes of Israel, defeated by the Assyrians in the eighth century BC. They regard only the Pentateuch as scripture, and their tenth commandment is an instruction to build an altar on Mount Gerizim. As Russell explains, the Samaritans rejected virtually all of the traditions of their southern Jewish neighbors: no Talmud, no Hanukkah. They still have priests descended from Levi, and they still sacrifice animals at Passover.

Despite their small numbers (and after having endured many historic bouts of persecution), the Samaritans enjoy more stability than the other religions of Heirs to Forgotten Kingdoms. Both Israelis and Palestinians respect them. “Our people were on the verge of extinction,” one man tells Russell, “and we have pulled ourselves back and built up our community, and now we are going nowhere: we are staying here.”

The Yazidis have rarely enjoyed such stability. Russell points out that they “keep a list of the seventy-two persecutions to which they have been subjected over the centuries.” Sadly, they have probably updated their list.

Russell explains that some Yazidi traditions, such as an annual bull sacrifice, predate their own religion and date back to ancient Assyrian practices. That they pray three times a day, revere the sun, wear girdles, and sacrifice bulls may point to the Greco-Roman mystery religion cult of Mithras. In short, a whole host of religious beliefs and practices stretching across at least two millennia flowed into what became Yazidism.

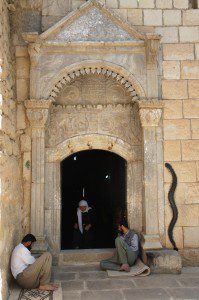

Unlike the Samaritans but like those ancient cults, the Yazidis are reticent about their teachings and rituals. Russell found few conversation partners willing to engage in any detailed discussion, but he did spend time with Yazidis in the Kurdistan city of Lalish. Random details: the Yazidis do not wear blue, and they do not eat lettuce.

The Yazidis understand a Sufi preacher named Sheikh Adi bin Musafir as the “earthly manifestation of Melek Taoos,” God’s appointed ruler of this universe, symbolized among the Yazidi with the figure of the peacock. They also associate Melek Taoos (transliterated in many different ways) with Azazael or Iblis, the angel who rebelled against God and became Satan. [As Russell points out, the Druze see the peacock rather than the serpent as the tempter in the Garden of Eden]. Because of this link, Muslims often deride the Yazidi as devil worshipers. According to Russell, the Yazidi understand Melek Taoos as “the rebel angel, but not as the prince of darkness.” After his rebellion and punishment, Azazael repented. He “extinguished the fires of hell with his tears” and again became chief among angels. “Far from worshiping the devil,” Russell concludes, “the Yazidis believe that there is no such thing.”

The chapters on the Mandaeans, Zoroastrians, Druze, Copts, and Kalasha are equally fascinating, but space does not permit the telling of those stories here.

Russell begins his book with an explanation of why the Middle East’s religious minorities are so imperiled today. He suggests that the past weakness of governments in the region created space for these communities to survive. More recently, stronger governments have unleashed or tolerated vicious waves of persecution (such as the 1915-1917 Ottoman slaughter in Armenia). Even more recently, religious minorities forced to take sides in local conflicts have made new enemies. Also, Russell suggests that with the decline of communism and nationalism in the Middle East, Muslims have turned their opposition to religious divisions. Governments see little gain in protecting small minorities, thus placing religious groups such as the Yazidis at great risk.

Russell includes a fascinating epilogue about the experience of religious immigrants in Dearborn, Michigan. Russell finds a Christian church service in Aramaic, with roots stretching back to the Baghdad-based Christian Church of the East. Iraqi’s Christian population has plummeted since 2003 (perhaps less than a third of what had been 1.4 million Christians remain); many — over a hundred thousand — have come to greater Detroit. Copts, Chaldeans, Druze, and Yazidis have made their way under duress to America. Russell finds that religious observance has become more important for the moment in these transplanted communities but also suggests that exile and assimilation will imperil their identities down the road.

History is full of the emergence, evolution, and disappearance or absorption of cultures, including their religions. One can climb hillsides in southern Germany and see — within a few hundred yards — the remains of Celtic walls, Roman fortifications, Christian monasteries, and Nazi amphitheater. Not everything makes it, a humbling thought. Some traditions gradually vanish; others are forcibly stamped out. My co-blogger Philip Jenkins has written recently about both the continued (if somewhat reduced) fade of mainline Protestantism and the threatened extinction of Middle Eastern Christian communities. Psalm 90, which identifies itself as a prayer of Moses, observes that God turns “people back to dust,” apparently the fate of many churches and communities as well. “Relent, Lord! How long will it be?” Isaac Watts adapted one of his most famous hymns from this psalm:

The busy tribes of flesh and blood,

With all their lives and cares,

Are carried downwards by the flood,

And lost in following years.

Perhaps it is only a small comfort, but Heirs to Forgotten Kingdoms might at least stave off some of that forgetting.

The bloody disappearance of minorities in the Middle East is one of the most significant religious developments of our age. Perhaps the only good news is that the United States has provided asylum for hundreds of thousands of those afflicted. Continuing to provide a safe haven for those suffering from religious persecution — let’s hope this is one aspect of immigration policy on which our elected leaders can agree. Welcoming these persecuted peoples in our midst is one small way for us to be modern-day good Samaritans, loving our neighbors.