I recently posted on changing ideas about the Virgin Mary’s role in the New Testament, suggesting that we see an upsurge of respectful interest in her towards the 90s of the first century. I am still grappling with the reasons for this change. I’d like here to explore one particular Bible passage that really gives me problems. It’s worth struggling with, though, because it says a lot about how the early church thought, and how it formed some critical habits of belief and devotion.

Revelation 12 has some phantasmagoric material that has been a mighty gift to visual artists over the past two millennia. Here’s the story from verses 1-7, which I will take from the KJV to avoid copyright issues:

And there appeared a great wonder in heaven; a woman clothed with the sun, and the moon under her feet, and upon her head a crown of twelve stars: And she being with child cried, travailing in birth, and pained to be delivered.

And there appeared another wonder in heaven; and behold a great red dragon, having seven heads and ten horns, and seven crowns upon his heads. And his tail drew the third part of the stars of heaven, and did cast them to the earth: and the dragon stood before the woman which was ready to be delivered, for to devour her child as soon as it was born.

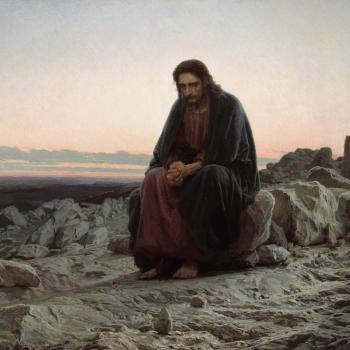

And she brought forth a man child, who was to rule all nations with a rod of iron: and her child was caught up unto God, and to his throne.

And the woman fled into the wilderness, where she hath a place prepared of God, that they should feed her there a thousand two hundred and threescore days. And there was war in heaven: Michael and his angels fought against the dragon …

The story of the Woman continues in verses 13-17

And when the dragon saw that he was cast unto the earth, he persecuted the woman which brought forth the man child.

And to the woman were given two wings of a great eagle, that she might fly into the wilderness, into her place, where she is nourished for a time, and times, and half a time, from the face of the serpent. And the serpent cast out of his mouth water as a flood after the woman, that he might cause her to be carried away of the flood.

And the earth helped the woman, and the earth opened her mouth, and swallowed up the flood which the dragon cast out of his mouth. And the dragon was wroth with the woman, and went to make war with the remnant of her seed, which keep the commandments of God, and have the testimony of Jesus Christ.

From early Christian times, interpretation of this passage followed a straightforward logic. The man child is obviously the Messiah, which in a Christian document has to be Jesus Christ. Therefore the woman who gave birth to him must be Mary. Even Epiphanius, the fourth century father who warned against excessive devotion to the Virgin, had no problem in applying verse 14 to her, where she receives the wings of an eagle. He understood this to refer to her mysterious passing from the world, which in later tradition became the doctrine of the Assumption.

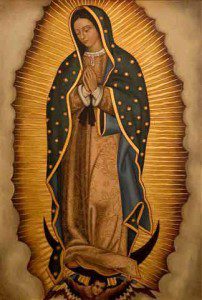

In Catholic visual art, Mary is often represented surrounded by twelve stars, and in various ways “clothed with the Sun.” That is the common format for reported visions and apparitions, such as Fátima in 1917. This association also explains the common linkage between such apparitions and visions of imminent End Times and cosmic war.

However much this passage laid the foundation for Mariology, there are multiple problems with any Marian linkage. In no way does the narrative here coincide with anything else we know about Jesus or Mary from any other source. Most of the action concerns the woman, while the child only appears briefly before being taken up to Heaven. The dragon also persecutes ton loipon tou spermatos autes, “the rest of her offspring.”

Revelation includes multiple mysterious figures, and in most cases they represent corporate originals rather than individuals. The Whore of Babylon is not intended to coincide with any particular Roman woman of her day, but is rather the Roman Empire itself. The Red Dragon also perfectly fits that imperial image. One of the best commentaries on Revelation is by Ben Witherington (Cambridge University Press, 2003), who offers a characteristically sane and lucid interpretation of this chapter on pp 163-74. He notes, for instance, that coins depict the goddess Roma as queen of heaven, so that the portrayal of the sacred Woman here might be a Jewish-Christian riposte to that.

So who is the woman clothed with the sun? Two obvious and closely related answers suggest themselves. One is Israel, the other is the New Israel, the Church. Either would fit common ways of reading in the Judaism of the time. Witherington particularly stresses the image in Isaiah of the woman in labor (Is. 26 16-18, 54.1-2 and 66.7-9), which is clearly meant to stand for Israel/Zion. He also places the wilderness references in the context of the Exodus narrative.

The most influential of those Isaiah passages in early Christian usage was 54.1-2, which Paul quoted in Galatians. Talking about the two sons of Abraham, born to Sarah and Hagar, he explains (4.24-28),

These things are being taken figuratively [allegoroumena]: The women represent two covenants. One covenant is from Mount Sinai and bears children who are to be slaves: This is Hagar. Now Hagar stands for Mount Sinai in Arabia and corresponds to the present city of Jerusalem, because she is in slavery with her children. But the Jerusalem that is above is free, and she is our mother. For it is written [quoting Isaiah]:

“Be glad, barren woman,

you who never bore a child;

shout for joy and cry aloud,

you who were never in labor;

because more are the children of the desolate woman

than of her who has a husband.”

Now you, brothers and sisters, like Isaac, are children of promise….

The idea of representing Israel as a woman is not unexpected, and perhaps the flight into the wilderness is linked to the church’s flight beyond the Jordan at the start of the Jewish rebellion in 66.

Depicting the Church as a woman would become a common literary device, which is used for instance in the Shepherd of Hermas, probably in the 140s. In that instance, she is an old woman, because “she was created first of all. On this account is she old. And for her sake was the world made.” (And Hermas came close to entering the New Testament canon). But the use of a human symbol is already evident.

I am certainly not making any radical suggestions here, as these are all common themes in various modern commentaries on Revelation. But I would stress one point that is not in that literature, namely that later believers were not actually wrong in associating the Woman of Revelation 12 with the Virgin Mary, as the Revelation passage profoundly shaped our earliest depictions of the Virgin.

Let me end on that cryptic note, and resume in another post.

Incidentally, for the incredible range of images of Mary in art, see the forthcoming exhibit at the National Museum of Women in the Arts, in Washington DC, due to start this December.