I recently posted about the sizable and often under-appreciated presence of Welsh people in America. As with many immigrant groups, the relationship between home country and new land was complex and remarkably long-lived. Generally, people did not just up and move to America, immediately losing all interest in their older countries. For one thing, it was surprisingly common for migrants to America to return to their homelands, at least temporarily, bringing all sorts of new ideas with them. In the Welsh case particularly, it’s hard to understand that national history without the American relationship – while successive waves of migration left a sizable mark on the American scene.

At least from the seventeenth century, Welsh radicals and religious dissidents saw America as a land where they could achieve freedom, and they repeatedly tried to establish new colonies. Early Welsh Independents arrived in New England, in settlements like Swansea, Mass.

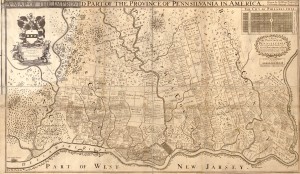

The Welsh, the Cymry, especially loved Pennsylvania, which was originally intended to be called New Wales. By 1700, the Welsh made up a third of Pennsylvania’s population. These migrants were chiefly Quaker and Baptist, as were many of their eighteenth century successors. The American Baptist tradition has its roots in a number of churches established in and around Philadelphia in the late seventeenth century, with a heavy presence of Welsh migrants and refugees. (See David Spencer’s classic history of Early Baptists of Philadelphia, 1877). Philadelphia’s influential Welsh Society dates from 1729. Much of colonial Pennsylvania history is a story of Lloyds, Morrises and Cadwaladers.

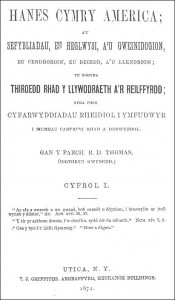

But the movement did not end in Penn’s time. At the end of the eighteenth century, Wales was a hotbed of radical and Jacobin sentiment, which was often linked to Nonconformist Protestant congregations. The political outlook of those dissenters is exemplified by the career of Morgan John Rhys (1760-1804). He joined the liberal Baptist congregation at Hengoed in Glamorgan, and became a minister at Pontypool, but in 1791, he realized that his true purpose was linked to the cause of France. He believed that the recent revolution ushered in the last days before the coming of Christ, and it was his role to ensure that the movement took a radically Christian direction. Armed with Bibles, he set off to convert France.

Back in Wales in 1793, he lived in Howell Harris’s Trefecca community, and used its printing press to produce the Cylchgrawn Cymraeg (Welsh Journal). This pioneering radical paper attacked slavery, taxation and the church establishment, it demanded educational reform, and it generally supported the cause of the new France. In 1794, fearing arrest, Rhys fled to America where he attempted to establish a Welsh community in the land of Beulah. This is now the less than idyllic Cambria County, in Pennsylvania. (Cambria is the Latin name for Wales).

Transatlantic solutions were natural in view of the strong Welsh element among American Baptists, represented by national leaders like Morgan Edwards and Samuel Jones. For three decades, the American denomination had experienced both radicalization and rapid growth, and there was a long tradition of cross-pollination with the Welsh homeland. Samuel Jones is the subject of a modern book aptly titled Transatlantic Brethren.

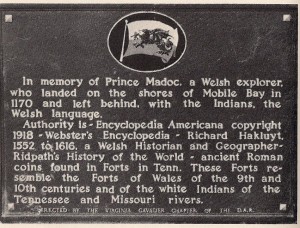

Cultural and radical enthusiasm now revived the legend of the “Welsh Indians.” There was a steadily growing myth about the medieval Prince Madoc who was said to have discovered America, and left a Welsh colony there. This led to an intensive search among the Indian tribes for linguistic traces of that settlement, and in 1791, the discovery of an allegedly Welsh tribe (the Mandans) was announced at the Llanrwst eisteddfod by William Jones of Llangadfan (1726-1795). William Jones was one of the more remarkable figures of a remarkable age, a Voltairean radical who was one of the first openly to espouse Welsh political nationalism. According to his account, the Welsh Indians were not only noble savages, they had retained much of the early law and religion of nature, as lauded by Enlightenment thinkers. And those Indians provided a precedent for Welsh settlement in the new republic.

The Welsh Indian myth inspired crazed genius Captain John Evans (1770-99) to explore North America in pursuit of those lost tribes. He never found them, of course – but his map of the American West was the essential basis of the Lewis and Clark expedition. (Meriwether Lewis was a Virginian of Welsh descent).

The cult of the Welsh Indians assisted the reception of Mormon ideas in the 1840s. The great industrial center of Merthyr Tydfil was a major Mormon center, the home of the paper Udgorn Seion (Zion’s Trumpet). There were six Mormon chapels by 1851, almost as many as the established Anglican church possessed. The Welsh were well represented in early Mormon settlement in America. (See the excellent site run from BYU).

Rhys’s Beulah was only one of several schemes to create a democratic Welsh homeland in America. William Jones sought the aid of the British and US governments for a planned settlement in Kentucky; but most of the movement lacked any grand plan. In the 1790s, as in the 1680s, burgeoning radical movements in mid-Wales were decimated by the flight to the freer shores of Pennsylvania.

For the Welsh, America was never a foreign country. Potentially, it was always Wales Across The Seas.

Successive migrant waves followed in the nineteenth century, as Wales exported highly skilled industrial workers and miners who were massively in demand in the newly industrializing America. Between 1840 and 1880, one of the great innovators in that revolution was the Welshman David Thomas, pioneer of the anthracite iron industry. Where you found iron and coal, steel and slate, copper and tinplate, you found the Welsh. They traveled to Pennsylvania and Ohio, New York and Wisconsin. Chicago, Youngstown and Scranton were among their great stamping grounds.

There are lots of local historical studies, mainly about Scranton and the coal country. (In passing, I have to share one book title I admire greatly: Cactus Cymry: Influential Welsh in the Southern Arizona Territory).

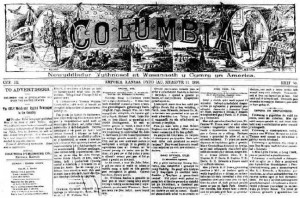

Most of these Welsh-American settlements emerged not from political idealism, but rather the rational economic choice to seek a better living. However, the good pay available to a largely skilled work force permitted them to recreate and sustain a Welsh environment with considerable authenticity. Prosperity permitted the establishment of numerous Welsh chapels and churches – sometimes Methodist, Independent and Baptist all in one town. In Pennsylvania, we hear in 1866 that Ebensburg, typically, “is a very Welsh place where there is an abundance of religious services, and several chapels in the town and in the country.” In the coal counties of Carbon and Luzerne, “the Welsh are very numerous”. Often, the language was still spoken, and eisteddfodau flourished in centers like Carbondale, “the Athens of the Welsh.” There was a sizeable Welsh-American publishing industry, and the newspaper Y Drych (The Mirror) was widely read from the 1850s.

Given these connections, revivals easily crossed the Atlantic. Wales was transformed politically by the Great Revival of 1858-9, a direct response to the American revival of 1857. One of the leading revival preachers in Cardiganshire was Humphrey Jones, a Wesleyan minster newly returned from America.

Religious revivalism was central to Wales’s burgeoning radical and pacifist traditions. We also see a strong sense of internationalism, a concern for the rights of small oppressed nations and peoples. The close Welsh linkage to America meant that Welsh radicals were profoundly affected by the plight of American slaves. Welsh Liberal nonconformists sympathized wholeheartedly with the slaves, the Republican Party, and the federal cause in the subsequent civil war. In 1853, Gwilym Hiraethog pioneered the genre of the Welsh novel with his Aelwyd F’Ewythr Robert, a popular piece based on Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

In turn, that US-derived radicalism transformed Welsh politics, driving an electoral revolution in 1868 that effectively gave Wales to the Liberal Party for sixty years. Later revivals – especially the legendary national event of 1904 – only reinforced that dominance. In turn, Wales’s 1904 revival was a prime influence on the American Pentecostal upsurge of 1906.

In religious history as so much else, what a mistake it is to look only on one side of the Atlantic.