This year marks a singularly grim anniversary in Christian history. In 2014, it is exactly four hundred years since the start of the horrific persecution that destroyed the once flourishing church in Japan.

When we think of persecutions on this scale, we normally tend to set them in an ancient or medieval context. The world of 1614, though, was in some ways remarkably modern, not least in terms of its literature and culture. Shakespeare had just retired, and Cervantes was about to publish the second volume of Don Quijote. Colonial North America already existed in crude form: St. Augustine, Santa Fe, Jamestown and Quebec City were already in existence, and the Dutch would soon be settling New Amsterdam. Yet contemporary events in eastern Asia seem to take us back to the earliest church.

During the sixteenth century, Catholic missions enjoyed stunning successes in Japan. By the end of that century, though, the official mood was turning more sour and intolerant. Persecution abated until 1614, when the violence intensified sharply following the establishment of the shogunate. Tokugawa Hidetada prohibited the practice of Christianity, so that “All missionaries, catechists and anyone who gives shelter to missionaries, and all seminarians, are expelled from the country.” Those who refused to obey faced the death penalty. These laws were renewed and expanded under his despotic successor Iemitsu (1623-1651), who was fanatically anti-Christian. Between the deadly year of 1614 and the 1640s, Japanese Christianity was rooted up, at the cost of (at least) tens of thousands of lives, probably more.

This persecution marked a lethal turning point in what had, up to that point, seemed to mark the spectacular progress of Christianity in Eastern Asia. Although we often recall Muslim/Christian conflicts, it was the Shinto/Buddhist nation of Japan that perpetrated one of the most thorough extirpations ever recorded of a church. The Japanese exceeded any Muslim successes in how totally they destroyed once-booming Christian communities. This movement had significant long-term effects for the direction of the Christian movement, as the annihilation of the Japanese missions decisively prevented Christianity resuming its movement towards global status, striking a dreadful blow against its progress in Asia. By eliminating potential rivals, both these campaigns contributed to maintaining the near-total European monopoly of Christianity.

In my next couple of posts, I will describe these events, and suggest their implications for wider Christian history.

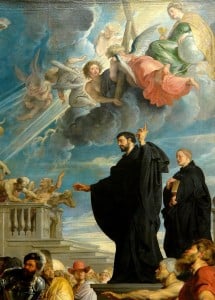

Catholic missions first arrived in Japan in 1549, when the Jesuit Francis Xavier landed at Kagoshima, in the southern island of Kyushu. The timing was important because Japan was at that time in political chaos, lacking a decisive central authority that might have excluded the alien new religion. Japan was in the era of Warring States, in which several different warlords contended for supremacy, each ruling in effect as an independent sovereign. One of the most significant was Oda Nobunaga, whose struggle to unite the country put him at odds with the powerful Buddhist sects. Tension with Japan’s traditional religious authorities predisposed him to favor new religions like the Christians, who were also useful in importing new military technologies, including modern artillery. Christians were rewarded by being allowed to proselytize freely.

The Jesuits directed their attention particularly towards the lords and gentry, the daimyo, knowing that in such a feudal society, the masses of ordinary people would have little alternative but to follow the lead of the upper classes. Significant numbers converted, and their long endurance under later persecutions shows that their Christian loyalties went far beyond merely obeying the commands of their landlords. By 1582, Japan had perhaps 200,000 Christians and 250 churches, an amazing growth in such a short time. At the height of Catholic power, around 1610, the Japanese church had at least 300,000 followers, concentrated in southern Japan, especially in Kyushu, in Omura and Nagasaki. (Just to put that number in context, the British colonies in North America would not have a population on that scale until after 1710).

But Japanese Christians were in a weaker position than most realized. From multiple sources, Japanese authorities were receiving alarming signals about what the long-term intentions of the visitors might be. Some loud-mouthed Europeans were heard boasting that soon, Japan would be a colony quite as subject to the Spanish empire as the Philippines was already. Such stories were reinforced by several groups deeply hostile to the Jesuit missions – from rival Catholic orders, notably the Dominicans, and from Protestant travelers, English and Dutch. Other more subtle signals pointed to the foreign nature of the faith, however hard the Jesuits tried to promote native clergy and a Japanese liturgy.

Warnings about foreign subversion found a ready audience in a new regime pledged to restore imperial unity. By 1590, Japan was reunited by one of Nobunaga’s generals, Toyotomi Hideyoshi. In 1603, another warlord, Tokugawa Ieyasu, created the strongly centralized Shogunate regime that remained in power until 1868. The new rulers had no sympathy for any movement that threatened to fracture Japanese unity, especially if that meant drawing in foreign imperialism. From the 1590s, Christians faced increasingly severe penal laws. Once secular protectors were removed or deterred, the next obvious targets were the clergy themselves. In 1597, Hideyoshi ordered the execution of 26 Christians, who were mutilated and then paraded for public display, before being publicly crucified in Nagasaki.

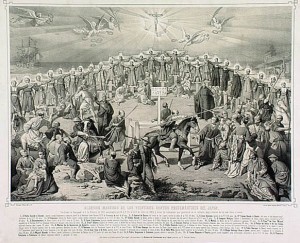

Local lords and daimyo were the first to withdraw their support, leaving the clergy and ordinary believers to face the consequences. We know the names of at least 1,200 who perished between 1614 and 1630, and one day in 1622, 52 Christians were executed in Nagasaki, by beheading and burning. This was “the Grand Martyrdom.” One English visitor “saw 55 martyred at Miyako at one time . . . and among them little children 5 or 6 years old burned in their mother’s arms, crying out: ‘Jesus receive our souls’. Many more are in prison who look hourly when they shall die, for very few turn pagans.” Executions were accompanied by extraordinary tortures and mutilations, which were so extreme that even later Catholic martyrologists shied from describing them in detail.

Yet the recorded cases are only a tiny minority of the actual persecutions, The martyrologies are heavily weighted towards remembering the names of Europeans, and of clergy, rather than of ordinary lay people or peasants, especially when these occurred in out of the way corners of the land.

The complete roster of victims ran into many thousands, not counting those who were imprisoned, mutilated or had their property confiscated.

Under lethal pressure, by the 1630s Christians were able to survive only in a few areas where they retained the sympathy of local lords. Even these refuges came under threat when Christians led the peasant rebellion in Shimabara, in western Kyushu, in 1637-38. This uprising was only suppressed after battles in which the government mobilized a hundred thousand men, and tens of thousands of Christians were among those massacred in the war and the ensuing repression. The outbreak was all the more terrifying to a society only just becoming accustomed to public order after long civil wars. Worse, the crisis pointed yet again to the strength of Christians along the southern coasts, regions that could easily be the targets of future naval assault: Christian enclaves could become a fifth column for foreign empires.

The government decided that Christianity was a menace to national security that had to be utterly rooted out, and the draconian penal laws were fully enforced. Already in 1636, Japan had opted to become a wholly closed society, fearing that any European visitors might bring unwelcome Christian influences, or might even be clergy in disguise. The government permitted very limited trade only with the Dutch, and then under rigidly limited circumstances. In 1640, a party of foolhardy Portuguese visitors was refused entry with the warning that “While the sun warms the earth, let no Christian be so bold as to enter into Japan.” Except for occasional martyrdoms recorded through the eighteenth century, Japanese Christianity largely vanished from official view.

The Japanese experience tells us much about the potential of religious persecution. On occasion, persecution can and does succeed, when applied with sufficient determination and violence, and repressive regimes did not need the technology available to a modern state, with its rich resources in means of communication and transportation. Much of the Christian religious decline in the Middle East involves gradual, long term, force applied over centuries, massive pressures to conform, reinforced in extreme cases by ethnic cleansing. In contrast, the Japanese story testifies to the power of governmental terror unleashed against a domestic population in intense bursts.

Contrary to the noble sentiment that is sometimes heard, you really can kill an idea.