Nearly every semester, I have the occasion to ask at least one class of students to read John Winthrop’s 1630 sermon, “Christian Charity, a Modell Hereof.” Most of my students have rather negative impressions of Puritanism, which in their minds probably equals religious intolerance and the execution of teenaged witches. I don’t assign them Winthrop to change their minds, but I do find that Winthrop’s sermon provides at least a rather attractive window into the Puritan mindset even for those who would vigorously disagree with some of its theology. Hierarchy, covenants, and divine sovereignty all feature prominently in Winthrop’s sermon.

Winthrop begins by observing the inequalities present among human beings and offering some reasons why God might have ordained those differences. Some are rich, and some are poor. Some are mighty, and some are in humble circumstances. Because God has ordained those differences, human beings at the top have no reason to boast in their own talents or accomplishments and human beings on the bottom have no reason to complain. Furthermore, because of such disparities “every man might have need of others, and from hence they might be all knitt more nearly together in the Bonds of brotherly affection.” Winthrop gets specific about those forms of cooperation, calling on the future settlers of Massachusetts to be merciful in their giving, lending, and forgiving.

Winthrop defines love as a “bond or ligament” that knits human beings together (and human beings to Christ). Human beings, sadly, are not very good at knitting themselves together. The problem, not surprisingly, is rooted in the sin. Because of Adam’s fall, “every man is borne with this principle in him to love and seeke himselfe onely.” Even worse, human beings really cannot do very much about their selfish dispositions. Instead, they continue in self-love “till Christ comes and takes possession of the soule and infuseth another principle, love to God and our brother.” Thus, love among Christians “is a divine, spirituall, nature; free, active, strong, couragious, permanent; undervaluing all things beneathe its propper object and of all the graces, this makes us nearer to resemble the virtues of our heavenly father.” Christian love “rests in the love and wellfare of its beloved.”

Having outlined these general principles, Winthrop turns to their application and the task at hand. He discusses the persons (“a company professing ourselves fellow members of Christ” — note, Winthrop is not addressing his thoughts to those he would term “wicked” rather than “regenerate”), their “work” (to “seeke out a place of cohabitation and Consorteshipp under a due forme of Government both civill and ecclesiasticall”), the end (to increase the body of Christ and preserve it from the corruptions of the world), and the means (love). “That which the most in theire churches mainetaine as truthe in profession onely,” he insists, “wee must bring into familiar and constant practise; as in this duty of love, wee must love brotherly without dissimulation, wee must love one another with a pure hearte fervently.” That’s my favorite sentence in the sermon. All Christians talk about loving one another. We have to actually do it, says Winthrop.

The closing paragraphs are the most famous parts of the address. “We are entered into Covenant with Him for this worke,” Winthrop states. If they safely reach Massachusetts, God will have ratified the covenant. If that occurs, the pressure is on. Should they “fall to embrace this present world and prosecute our carnall intentions,” God will break out in wrath against them. ” Now the onely way to avoyde this shipwracke,” Winthrop explains, employing a most appropriate metaphor, is for the colonists to actually remain “knitt together, in this worke, as one man.” Should they fulfill the covenant, God will bless them, and “men shall say of succeeding plantations, ‘the Lord make it likely that of New England.'” Winthrop’s most famous passage uses ample hyperbole: “wee shall be as a citty upon a hill. The eies of all people are uppon us.”

Winthrop’s speech, and in particular his vision of the “city upon a hill,” has often been misused. See Ronald Reagan’s use of the metaphor in his farewell address. Winthrop becomes “a freedom man” bent on founding a hub of commerce open to everyone.

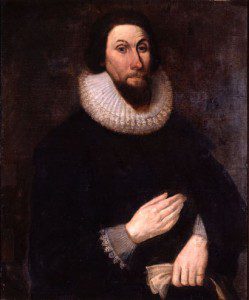

My students typically comment on both the utopian and exclusivist elements of Winthrop’s vision. The bit on God choosing some people to be rich and some to be poor, they quite rightly suggest, sounds more pleasing when one is rich. Even in his most famous portrait, Winthrop does look more than a touch supercilious. And there wasn’t any obvious place in Winthrop’s vision for those who had not experienced regeneration or for native peoples. These limitations would plague Massachusetts in the years ahead, as the children of the early settlers often did not have the experiences of regeneration that would enable them to become full members of the colony’s churches. The early years of the Plymouth colony had already brought about some grisly encounters between pilgrims and natives, and within six years of the establishment of Massachusetts Bay Winthrop’s settlers were engaged in a barbarous war against the Pequot.

Still, when I read Winthrop, I can’t help but have the early years of Virginia in mind (and I’ve just been rereading Edmund Morgan’s American Slavery, American Freedom). It’s a thoroughly disheartening tale in which greedy power players in the early years of settlement exploit both natives and indentured servants. There’s hardly any cooperation among the colonists and hardly any regard for human life. Even after the most precarious years had passed, in the early 1620s the death rate for indentured servants in Virginia was shockingly high. I’m not trying to superficially suggest that early New Englanders had less regard for self than Virginians (and I know that I’m stepping into the terrain of co-bloggers with far more knowledge about this time period). I presume, though, that Winthrop was well aware of the horrors of early Virginia. Whatever one might think about the theological elements of his prescription, “A Modell of Christian Charity” is a rather realistic reflection on the human condition and a stirring call for Christian cooperation and love. In how many churches today do the members feel themselves bound together by love as strong as the “bond and ligament” described by Winthrop?