I recently posted about the enduring influence of Dualist versions of Christianity, the idea that the material world is a diabolic creation, from which Christ came to free us. These views were widespread and enduring in the early and medieval church, and flourished somewhere in all eras prior to the fourteenth century – even later in some regions. I am intrigued both by the enduring appeal of such ideas, and their distinctive use of Biblical texts.

Around 970, the Orthodox Presbyter Cosmas preached furiously against the Bogomil heretics who were gaining ground so rapidly across the Balkans. He condemned their views, which exactly followed the Dualist “package” I have already described. Because matter was evil, they rejected any religious symbols that used it, or any institution that taught their use. That meant rejecting crosses, icons, churches, and all sacraments, including the eucharist and baptism. “And how can they call themselves Christians, when they don’t have priests to baptize them, when they don’t make the sign of the cross, when they don’t sing priestly hymns and don’t respect priests?” They scorned the veneration of the Virgin Mary. Around 1100, a Byzantine writer recorded a Bogomil leader speaking in equally damning terms of the institutional church: “And as for the churches, woe is me – he called our sacred churches the temples of devils, and our consecration of the body and blood of our one and greatest High Priest and Victim he considered and condemned as worthless.”

And where did they get these monstrous ideas? Why, largely from the gospels themselves. When you read the views of Dualist churches like the Bogomils and Albigensians, you are immediately struck by how thoroughly immersed they are in the New Testament, and especially the gospels. Given that limitation, and without the vital structure provided by the Old Testament (which they rejected), they are able to deploy their texts quite consistently.

Now, orthodox believers had long protested against heretical misuse of scripture. As far back as the second century, Irenaeus complained that “In like manner do these persons patch together old wives’ fables, and then endeavor, by violently drawing away from their proper connection, words, expressions, and parables whenever found, to adapt the oracles of God to their baseless fictions.” (See Peter Leithart’s recent post on this at First Things).

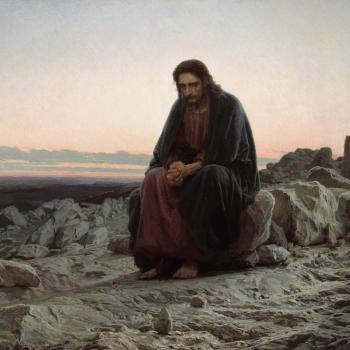

Medieval Dualists were creative in rooting their doctrines in scripture. A number of texts can be used to support the idea that the Devil is the Lord of the present world. Bogomils cited the temptations in the wilderness to prove that the Devil held power over the world, and could therefore offer it to Jesus (Matthew 4.8-9). Jesus himself speaks of the Devil as Lord of this World (ho tou kosmou archon, John 14.30). Many of the texts commonly used today to support predestination also lend themselves to those purposes, especially the parable of the wheat and the tares (Matthew 13.24-30).

If the world is of the Devil, then a church that claims material power and acts sacramentally must be his servant.

Cosmas reports one distinctive reading:

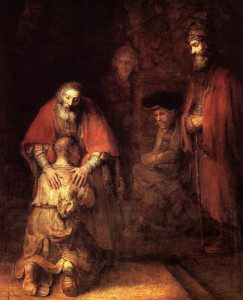

Having heard the parable in the gospels about the two sons, they consider Christ the older son, and the younger one who deceived his father they consider the Devil, and they call him “Mammon,” and they call him the creator and builder of the things of the earth. And he commanded men to marry, to eat meat, and to drink wine. And while simply defaming everything of ours, they consider themselves heavenly dwellers, and people who marry and live in this world they call the “servants of Mammon.”

Bogomils drew on the puzzling parable of the unjust steward (Luke 16.1-13), which they saw as an account of the revolt of the fallen angels. In this reading, Satan/Satanael himself was the “steward” who used those material promises to lure other angels into rebellion, forgiving their “debts.” (Janet Hamilton and Bernard Hamilton, eds., Christian Dualist Heresies in the Byzantine World, 183).

Revelation too offered several valuable passages that could be read to justify Dualist theology.

It would be intriguing in fact to compile a list of these passages that so inspired dissident groups, a kind of Heretics’ Bible. Just which texts, especially from the gospels, lend themselves so powerfully to religious dissidence? I suspect we would find the same passages reused time and again through the centuries.