There are certain columns those with an interest in the history and present of American Christianity should read. The Wall Street Journal‘s weekly Houses of Worship essay (see the recent pieces on Jackie Robinson and Robert Edwards). Our own Philip Jenkins’s essays at Real Clear Religion (see his recent column on the anniversaries of Waco and Oklahoma City). Naturally, there are many high-quality blogs on the history of Christianity, too many to mention. Here’s another regular column to add to the mix: the Christian Century‘s Then & Now feature, edited by Ed Blum.

This week’s Then & Now column is from Heath Carter, who teaches at Valparaiso and is working on a manuscript (per his website) about “social Christianity” in the early twentieth century was shaped by decades of working-class activism. It would also be worth reading Heath’s column at Religion in American History about the recent NYT piece on historians and capitalism.

Here’s an excerpt from Carter’s column:

In the United States, contemporary Christianities rarely challenge the economic status quo. On the contrary, they typically celebrate the ever more elusive and yet no less alluring “American Dream.” Christians are as enamored with upward mobility—and all the iPads, designer countertops, and luxury sedans that come with it—as the next person.

Meanwhile, we abide and even endorse an unbiblical distinction between “fiscal” and “moral” issues. It is little wonder that, at the Lutheran university where I teach, students assume that corporations—as much “persons” as you or I according to the Supreme Court—are, by their very nature, exempt from the Golden Rule. “Nature” is the key word here, for in the minds of many our free enterprise system, championed by Democrats and Republicans alike, seems as natural as the earth and sky.

I agree with most of the second paragraph, much less so with the first. I don’t think it’s true that mainline denominations and the American Catholic Church, to name two examples, “rarely challenge the economic status quo.” I’m a bit out of date, but at the last Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) General Assembly I attended, there was an abundance of challenges to the economic status quo. On the other hand, what is true of mainline denominations is rather less true of the average mainline pulpit. If Carter substituted “contemporary evangelicals” for “contemporary Christianities,” perhaps his statement would be more true. Even so, many contemporary evangelicals do challenge the economic status quo, just from the right rather than the left. There is such a diversity of denominations, churches, and opinions that any clear voice on such matters is impossible for Protestants. The Catholic Church is a more effective critic, I would suggest.

It is true that many Christians “endorse an unbiblical distinction between ‘fiscal’ and ‘moral’ issues.” I agree that some Christians exempt business and businesspeople from the Golden Rule, believing that cutthroat competition — if harmful to certain parties — works out best for our society as a whole. Our very system of government, to a substantial extent, gives its blessing to the pursuit of self-interest and relies on a system of checks and balance to compensate for human depravity.

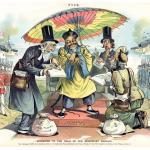

Carter continues by pointing to the massive gaps in wealth and income between the top echelon of American society and the vast bulk of Americans, and yes, it is reminiscent of those Gilded Age fountains that bubbled with champagne. Statistics do show that middle-class incomes have stagnated in recent years. That is the problem, in my view, rather than a rise in inequality per se . I’ve never been convinced that it’s immoral for the rich to get rich more quickly than the poor or the middling classes, as long as the real incomes of ordinary Americans are also rising. This reminds me of Margaret Thatcher’s final appearance in the House of Commons, in which she eviscerated an opponent for — in her view — “saying that he would rather that the poor were poorer, provided that the rich were less rich. That way one will never create the wealth for better social services, as we have. What a policy. Yes, he would rather have the poor poorer, provided that the rich were less rich. That is the Liberal policy.” During the Gilded Age, the incomes of ordinary Americans did rise rapidly. I would argue that the income and wealth chasm between those at the top and those at the bottom was not the problem. To the of my knowledge, both the income and purchasing power of American workers expanded considerably in the late 1800s, which was also a time of falling prices. The very real and serious problems were the boom-and-bust cycle of the economy, the corresponding insecurity for workers, and the fact that due to a massive imbalance of both power and suppler and demand, employers could cruelly mistreat their workers by subjecting them to dangerous working conditions for relatively little pay.

Carter points to the activism of countless working-class Christians (and a few allies) during this time period:

Galvanizing the debate were myriad ordinary Christians who sought to reform both the emerging industrial order and those churches that unquestioningly accommodated it. These included thousands of trade unionists, who battled both intransigent bosses and scab ministers. Workers were quick to remind their religious betters that Jesus, a carpenter after all, had insisted that “the laborer deserves to be paid” (Luke 10:7).

And despite the economic status quo preaching of figures like Henry Ward Beecher and Dwight Moody (this per Carter), there were increasing numbers of Protestant evangelicals quite comfortable with preaching social and economic reform. The evangelist J. Wilbur Chapman comes to mind, for instance.

A closing thought: one major reason that more Christians are not critical of capitalism is a simple belief that it works pretty well compared to most economic systems. It might not square very well with scripture or with the ethics of Jesus, but it works (at least in the minds of many American Christians). Many progressive Protestants criticize evangelicals for ignoring science — in favor of revelation — when it comes to positions on everything from evolution to homosexuality. Economics is far less of a science, but I can imagine that many evangelicals look at their society and suspect that capitalism had something to do with the massive amount of prosperity that Americans, on average, enjoy. That doesn’t mean that Christians should not raise their voices against exploitation and greed, or that the Kingdom of God and the Kingdom of Mammom should be separate in terms of ethics. Indeed, one could effectively argue that many northern European societies provide both higher levels of equality and social mobility. Nevertheless, the prosperity of the United States — stunning by historical and global standards despite all our problems — tends to blunt Christian criticism of American capitalism.