I have recently been posting about the end of the church in Roman Britain, mainly as a case study in how churches die. Just to recap, the old church disintegrated after 450 or so, at least in the south and east of the island – that is, southern and Eastern England – but it survived and flourished in the north and west: in Wales, the West Country, and Northwest Britain. When we look at the survival of the faith in extreme conditions of violence and chaos, when institutions are on the verge of collapse, there is one major factor that perhaps we underestimate, and that is monasticism.

Today, Protestants might assume that the best way of ensuring continuity of faith would be access to scriptures, but at least in the so-called Dark Ages, it is the monasteries and convents that really demand our attention. Across the Eastern world, it was the monks who seized the imagination and respect of outsiders, including Muhammad himself. Rightly or wrongly, they saw the monks and nuns and their houses as the heart of the Christian faith.

In the East, monasticism originated in the third century, and was booming during the fourth. The movement was slower to take hold in the West, where the key figure was the very influential bishop St. Martin of Tours (316-397). Martin developed a monastery at Marmoutier (Majus Monasterium), which spread the monastic vogue in Gaul and the West. In 410, another key house was founded at Lérins.

By the time that Roman rule ended in Britain in 410, then, monasticism was a new vogue, and it probably made only slow progress in the island before the old Roman Christian society collapsed in the mid-fifth century. Very shortly after that time, though, evidence for British monasticism surges. Of course, it is difficult to know exactly what to make of later medieval saints’ lives, which portray their heroes as abbots and monks in the familiar medieval mode, back projected to implausibly early eras. But we have plenty of strictly contemporary early material, from the fifth and sixth centuries.

Partly, this evidence is archaeological, with early sites throughout western Britain and Wales, notably Tintagel in Cornwall. But we also have well dated literary texts. Around 475, for instance, the Gaulish bishop Sidonius Apollinaris describes his meeting with a Briton named Riochatus “priest and monk [antistes ac monachus], and thus twice a stranger and pilgrim in this world.” In the 540s, monks feature repeatedly in the writings of the British writer Gildas, who denounces the kings of his time in the west and south-west. Maglocunus, for instance, a powerful Welsh ruler, had in the past renounced his secular authority for a monastery, and taken vows – although he later violated them. Another British king, Constantine, apparently disguised himself as an abbot in order to assassinate two rival princes.

Although not strictly contemporary, the historian Bede (writing 731) had excellent sources about his native Northumbria. We should therefore believe him when he tells us that around 600, the pagan king Aethelfrith slaughtered several hundred monks from the north Wales abbey of Bangor, who had massed to support British forces in a battle at Chester.

Monks and monasteries, it seems, had become familiar parts of the social and religious landscape. During the sixth century we find the origins of many critically important British religious houses, which were widely imitated in the nascent Irish church.

So why did these monastic houses matter so much? From a modern point of view, they were so important because of their literary and cultural works, as they wrote and copied so much of what became our indispensable historical sources for a very dark era. From a contemporary perspective, though, their importance was very different.

Partly, monasteries were crucial centers of evangelism. They spread the faith into the countryside, breaking the old assumption that Christianity was an urban faith. Monasteries were often located far from the centers of civilized life and authority, in areas where the church would scarcely have penetrated otherwise. That work became all the more important as the ancient cities and trade routes declined, and the centers of wealth and power moved into the old country areas.

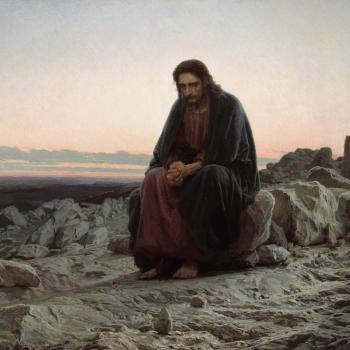

In the spiritual context of the time, moreover, monks and solitaries of various kinds offered heroic role models. Their austere lives proved their obvious holiness, and made them champions against the forces of evil believed to dominate the world. Monasteries and hermitages were God’s fortresses in the wilderness, bases of operations for constant spiritual warfare. Monks epitomized the Christian ideal, giving them a status that potentially rose above that of the secular world. Even a great king like Maglocunus dreamed that he might aspire so high, although he ultimately fell short.

That fortress analogy would prove literally correct during times of chaos, when cities fell. But the monasteries remained, and retained the loyalty of ordinary believers of all classes. We see this most clearly in the Middle East, where ancient Christian monasteries carried on for centuries after Islam had come to dominate the surrounding regions. Even aggressive barbarians often thought twice before molesting such radiant centers of spiritual charisma. (As Aethelfrith’s story tells us, though, monks could only retain this protected status if they steered well clear of overt political involvement)

So there is my answer for why Christianity died in the south and east of Roman Britain. The church’s institutional structures in those areas dissolved about fifty years too early, before a monastic movement could have established an alternative framework for faith, one better suited to the bloody and confused times that lay ahead.

At a time when Christian society was falling into ruins, then, the faith survived through the work of intimate communities devoted to maintaining its values and beliefs at the most fundamental level. I stress that this is a matter of distant history, and has no relevance at all to modern conditions.