I have a long-standing interest in the early church and the church of Late Antiquity – depending where you are located, that includes the era we sometimes call the Dark Ages. This fascination, for instance, led me to write books like my Jesus Wars. The more I think about it, the more I realize just where this interest comes from. Little did I realize it at the time, but I grew up in a landscape utterly marked by the early church, and an ancient kind of Christianity.

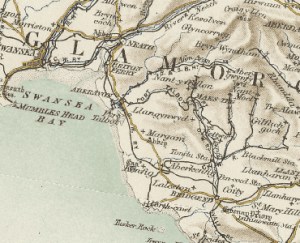

I come from South Wales, from a town called Port Talbot. Welsh people have always been great migrants. They love to relocate to distant parts of the world, where they write moving memoirs of how wonderful it is to live in Wales. Often, these accounts describe an industrial world, of mines and steelworks, and that was exactly the landscape I knew – up to the 1980s, Port Talbot was home to one of Europe’s largest steelmaking complexes.

Beneath that world, though, an older realm lay, although most of us growing up in that era knew virtually nothing of it. A critical clue came from the steelworks itself, which was named the Abbey. It commemorated a rich twelfth century Cistercian abbey at nearby Margam, a vast local landholder. As with all the monasteries, Margam was annexed by local landowners at the Reformation, and most of the buildings perished. What survived was a few fragments, including the really beautiful abbey church.

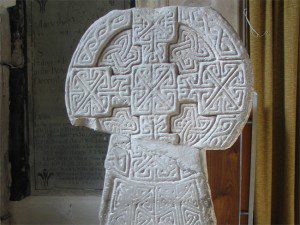

A little digging, though, took us much further into the past. Margam also houses a precious Stones Museum holding the dozens of Christian memorial stones found at or near the site. Ranging from the fifth century through the eleventh, these showed just how active the settlement had been in the area through the darkest of Dark Ages. Wikipedia calls it “one of the most important collections of Celtic stone crosses in Britain.” The site showed beyond any reasonable doubt that Margam itself housed a much older monastery from Celtic times, probably from the sixth century and perhaps long before.

While it is very difficult to reconstruct the history of this region in any detail, we know that sixth and seventh century Wales had surprisingly good contacts with the Mediterranean world, demonstrated by the presence of high-quality pottery, and the use of Continental and Byzantine styles in memorial inscriptions. Near Margam, remarkably, we even find a seventh century copper coin from Byzantine Alexandria.

But Margam was only a small part of a much larger Celtic Christian landscape. The town stands on a highly developed coastal stretch between the towns of Neath and Bridgend, a distance of twenty miles now spanned quickly by the M4 motorway. Incidentally, this motorway follows fairly closely the old Roman road from Cardiff to Carmarthen, which presumably mapped the original spread of Christianity in the fourth century. (Welsh names beginning with Caer- usually recall Roman memories, from the word castra, fortress). The Roman road was still functioning when the first Christian settlements were established.

Neath itself was a Roman fort, and had its own Cistercian abbey. Moving south, Baglan was another old Celtic church with its ancient stones. Still in my time, you could see the remnants of the twelfth century church that lay behind the handsome Victorian replacement. Later traditions take the settlement back to a sixth century missionary saint.

A few more miles brought you to Margam – but that raised an interesting question. Why was Margam there in the first place? Throughout Britain and Ireland, we see a common pattern in the placement of ancient churches and monastic settlements, which usually lay conveniently close to centers of royal power. Missionaries and church leaders wanted to be close enough to the kings and chieftains to take advantage of their protection, and to influence affairs, but not so close as to fall under their total control. Often, over time, the church survived as a powerful center, while the older royal seat decayed or vanished. A great church like Margam must have followed some pattern like this, but where was the original “palace” or royal villa, the warlord’s hall (llys)?

Almost certainly, the royal settlement was at a village called Kenfig, an amazing example of continuity from Roman times through the Middle Ages. It became the site of a thriving medieval borough, before it disappeared entirely under shifting sand dunes. For centuries now, it has been literally a lost city, “The Buried City of Kenfig.” Kenfig may have been the capital of a cantref, an early Welsh political unit that would have run between the rivers Tawe and Ogwr/Ogmore. (In an earlier life, back in 1988, I actually wrote an article on this region in Cambridge Medieval Celtic Studies!) From perhaps 500 through 1050, the region I am discussing would thus have been the cantref of Margam, with its royal center at Kenfig and its principal church at Margam proper.

The lovely Kenfig area also has the village and church of Mawdlam, named from the church of Mary Magdalene. With Kenfig, it’s a legendary beauty spot: in fact, part of “the largest active sand dune system in Europe.” Cornelly nearby recalls a church of St. Cornelius.

Near Kenfig we find the site of the hermitage of Theodoric. Accurately or not, this is believed to be the monastic site where a local king retired after resigning his crown, somewhere around 600. Bringing very different worlds together, this king in south Wales bore a Germanic or Gothic name, and he named his own son Maurice, after the reigning Byzantine Emperor of the day.

Near Bridgend, old Christian settlements abound (and there was also a Roman station somewhere nearby). Ewenni has its twelfth century Benedictine priory, but as at Margam, this was built over much older foundations.

Nearby is Merthyr Mawr, an evocative name. “Merthyr” is a well known Welsh place-name, which derives from martyrium, a site of martyrdom. This did not necessarily imply violent death or persecution, but rather a remote place where monks and hermits dedicated their lives in absolute devotion to God, renouncing all. Merthyr Mawr is thus the Great Martyrium. We know from land charters that Celtic bishops were developing their landed estates in the Ewenni-Merthyr Mawr area at least from around 700, and Merthyr Mawr also has a rich crop of early Christian memorial stones. However little survives to see today, once this must have been a flourishing settlement.

Many Welsh place-names include the element Llan-, and these are found throughout the area. A llan- is an enclosure, marking an old Celtic church or monastery, as in Llanfihangel, Church of the Angels. Once you move a little east of Bridgend, you find some of the most important Celtic monasteries in the whole British Isles. This area, the Vale of Glamorgan, had in its day been the most Romanized area of Wales, with a concentration of villas, and some of those presumably converted directly to become monasteries or churches. Llantwit Major and Llancarfan were the centers for the influential early saints Illtyd and Cadoc.

Llandough near Cardiff may have been quite as important in its day, and has produced some remarkable archaeological finds in recent years. In fact, the early monastery here seems to have grown directly out an older Roman villa settlement, suggesting Christian continuity through the fifth century.

Just think of that concentration – a major Celtic monastery every eight or ten miles or so, and I’ve only begun to sketch the area.

As a child, even as a teenager, I knew next to nothing of any of this. I don’t think I even visited the Margam Stones Museum until I was seventeen or so. Since then, though, I have been fascinated with that whole lost Christian world, especially its Celtic dimensions.

I’ve spent the rest of my life making up for that lost time.