When I was a kid, I lived in a neighborhood with a bunch of other boys right around my age. And so all throughout the year, but especially in the summer, my brother and I would often leave home to play with our friends. We might go swimming in Mike’s backyard. We might play the board game RISK at Chuck’s house. We might explore in the woods behind Brian’s house. Or we might play baseball or football in the empty lot down the street. But wherever we got off to in the neighborhood, all my mom had to do was step out on our front porch and yell, “Boys, time to come home for supper!” and we’d wrap up what we were doing and head home. Mom didn’t have to specify which boys she was calling. We just knew by the sound of her voice that she was our mom—not Jeff and Justin’s down the street.

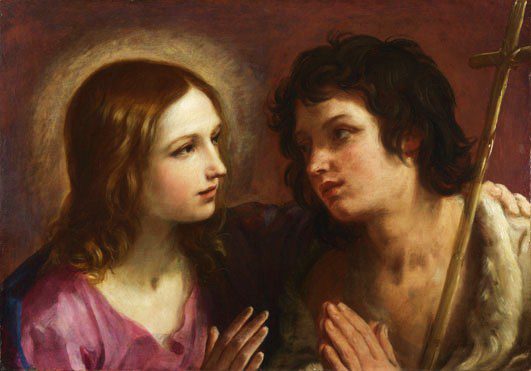

In this passage from John, Jesus presents us with the imagery of a shepherd and its sheep—perhaps beckoning back to King David’s psalm about the Lord as his shepherd. But there’s something about the way Jesus describes his relationship with his sheep—something both warmly tender and fiercely protective at the same time—that can almost sound more, dare I say, motherly:

“My sheep listen to my voice; I know them, and they follow me. I give them eternal life, and they will never perish. No one can snatch them away from me” (John 10:27–28).

Earlier in the Gospel of John, Jesus uses motherly imagery to describe this gift of eternal life. He tells the Pharisee Nicodemus, “Unless you are born again, you cannot see the Kingdom of God” (3:3).

Nicodemus takes Jesus’s words quite literally and asks, “What do you mean? How can an old man go back into his mother’s womb and be born again?” (3:4)

Jesus answers, “I assure you, no one can enter the Kingdom of God without being born of water and the Spirit. Humans can reproduce only human life, but the Holy Spirit gives birth to spiritual life” (3:5–6).

The Holy Spirit gives birth, Jesus tells Nicodemus. This is what it means to be “born again”—to be birthed into the Kingdom, birthed into resurrection life. And as with our physical births into this life, our birth into resurrection life was not without pain and suffering and labor.

Perhaps this is why medieval Christian writers sometimes depicted Jesus as our spiritual mother. It wasn’t that they didn’t know Jesus was born as a man—or that they had some kind of hidden “feminist agenda.” They simply looked what Jesus went through to give us resurrected life and saw that the closest comparison was a mother birthing a child.

So the medieval writer Julian of Norwich writes this:

Our true mother, Jesus, he who is all love, bears us into joy and eternal life; blessed may he be! So he sustains us within himself in love and was in labour for the full time until he suffered the sharpest pangs and the most grievous sufferings that ever were or shall be, and at the last he died. And when it was finished . . . he had born us to bliss.

Likewise, the medieval French nun Marguerite of Oingt writes this prayer:

For are you not my mother and more than my mother? The mother who bore me labored in delivering me for one day or one night but you, my sweet and lovely Lord, labored for me for more than thirty years. Ah, my sweet and lovely Lord, with what love you labored for me and bore me through your whole life. But when the time approached for you to be delivered, your labor pains were so great that your holy sweat was like great drops of blood that came out from your body and fell on the earth. . . . Ah! Sweet Lord Jesus Christ, who ever saw a mother suffer such a birth! For when the hour of your delivery came, you were placed on the hard bed of the cross . . . and your nerves and all your veins were broken. And truly it is no surprise that your veins burst when in one day you gave birth to the whole world.

This imagery might sound strange to our ears, but it’s not without precedent in the Gospels themselves. In addition to Jesus telling Nicodemus that the Holy Spirit gives birth to new life, Jesus also compares himself to a mother hen. Just after Jesus calls King Herod a fox, he breaks down weeping for Jerusalem: “O Jerusalem, Jerusalem, the city that kills the prophets and stones God’s messengers! How often I have wanted to gather your children together as a hen protects her chicks beneath her wings, but you wouldn’t let me” (Luke 13:34).

The medieval writer St. Anselm draws on this language when he writes this prayer:

But you, Jesus, good lord, are you not also a mother? Are you not that mother who, like a hen, collects her chickens under her wings? Truly, master, you are a mother. For what others have conceived and given birth to, that have received from you. . . . . You are the author, others are the ministers. It is then you, above all, Lord God, who are mother. . . .

Christ, mother, who gathers under your wings your little ones, your dead chick seeks refuge under your wings. For by your gentleness, those who are hurt are comforted; by your perfume, the despairing are reformed. Your warmth resuscitates the dead; your touch justifies sinners. . . . Console your chicken, resuscitate your dead one, justify your sinner. May your injured one be consoled by you; may [they] who of [themselves] [despair] be comforted by you and reformed through you in your complete and unceasing grace. For the consolation of the wretched flows from you, blessed, world without end, Amen.

When I was growing up, my parents had an unspoken rule that they would share everything with each other. There would be no secrets between the two of them. This made things a bit awkward when I went to ask my dad for advice about proposing to Andrea. I knew that if my mom were to find out, odds were that she would say something to my aunts out of excitement. And then who knows who else would have learned and how quickly it might have even gotten back to Andrea.

So I asked my dad not to tell my mom and promised to tell my mom before I asked Andrea. Then the morning of the day I planned to ask Andrea the big question, I showed my mom the ring and told her my plans. And try as she may, there was no concealing the fact that she already knew. Apparently I had underestimated her, though, as she hadn’t spoken a word of it to anyone else.

When I called my dad out on telling my mom, he confessed and said, “Your mom and I don’t keep secrets.” And I thought, That information would have been useful three weeks ago when I asked you to keep a secret!

Even so, it was comforting to know that my dad and my mom were on the same page. They both wanted what was best for me. Which, incidentally, is kind of how my mom blew her cover. When I told her the news, she immediately started asking me a bunch of practical questions about how a 20- and 21-year-old would be able to survive on our own. Which isn’t how moms tend to respond to that kind of news—at least not initially.

In this passage from John 13, we see Jesus describe his relationship with God the Father the same way. How does Jesus know his sheep will never perish? First, he says, “No one can snatch them away from me” (13:28). But then he adds immediate that the Father has given him the sheep, “and he is more powerful than anyone else. No one can snatch them from the Father’s hand” (13:29).

So which is it? That we can’t be snatched from Jesus’s hand? Or that we can’t be snatched from the Father’s hand?

Jesus’s response to this question is, You’re exactly right! “The Father and I are one” (13:30)!

Jesus and the Father are perfectly united in not only wanting what’s best for their children but also in ensuring that they receive it. And what’s best for their children, says Jesus, is eternal life—resurrected life; life free of sin, pain, and death; life to the fullest. This is very good news.

As Julian of Norwich describes it,

The mother may allow the child to fall sometimes, and to be hurt in diverse manners for its own profit, but she may never allow that any manner of peril come to the child, for love. And though our earthly mother may allow her child to perish, our heavenly Mother, Jesus, may not allow us that are His children to perish: for He is All-mighty, All-wisdom, and All-love; and so is none but He,—blessed may He be! But often when our falling and our wretchedness is shewed us, we are so sore afraid, and so greatly ashamed of our self, that scarcely we find where we may hold us. But then wills not our courteous Mother that we flee away, for He wills that not at all. . . . But He wills then that we use the condition of a child: for when it is hurt, or afraid, it runs hastily to the mother for help, with all its might. So wills He that we do, as a meek child saying thus: My kind Mother, my Gracious Mother, my precious Mother, have mercy on me: I have made myself foul and unlike to You, and I nor may nor can amend it but with thine help and grace. And if we feel us not then eased forthwith, be we sure that He uses the condition of a wise mother. For if He see that it be more profit to us to mourn and to weep, He suffers it, with care and pity, to the best time, for love. And He wills then that we use the property of a child, that evermore of nature trusts to the love of the mother in wellbeing and in woe.

Although her language is a bit old-timey and hard to follow at times, Julian is essentially saying that Jesus cares for us more than an earthly mother ever could. This isn’t a knock against mothers, just as it’s not a knock against fathers to say that God the Father cares for us more than our fathers ever could.

Instead, it’s the good news to all of us that, no matter what your family situation is like, in Christ you have a new family. This new family will never let you perish or be snatched away. For this family has both the desire and the power to keep you safe and to give you abundant life to the fullest. And so Marguerite of Oingt, who left her family to become a nun, could write the joyful prayer:

My sweet Lord, I gave up for you my father and my mother and my sister and my brothers and all the wealth of the world. . . . You know, my sweet Lord, that if I had a thousand worlds and could bend them all to my will, I would give them all up for you . . . for you are the life of my soul. Nor do I have a father or mother besides you, nor do I wish to have.