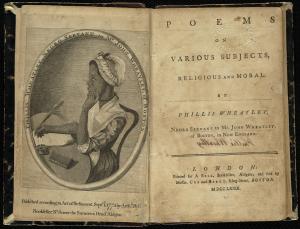

In case you missed it, last month there was a bit of a blogosphere dust-up when religion writer Jonathan Merritt tweeted that it was “weird” that evangelical historian Thomas Kidd used the word “evangelical” to describe Phillis Wheatley, the first published African-American poet.

A number of evangelical historians came to Kidd’s defense (as is well documented by historian John Fea), and the conversation quickly shifted to the questions of how to define “evangelicalism” and who should do it.

I followed this conversation with some amusement because I was at the same time reading Merritt’s latest book, Learning to Speak God from Scratch, where he argues that Christians should be liberated to play with religious words to breathe new life into them, and he notes that the advent of dictionaries and their seemingly rigid and prescriptive definitions have hindered our ability to do so.

In light of the argument of his book, Merritt’s insistence that Kidd use the word “evangelical” in conformity with his seemingly prescriptive definition seemed a bit—for lack of a better word—weird.

If Merritt had applied the approach of his book to the word “evangelical,” I think he would have seen how the word, like many religious words, has morphed and evolved over time and is used in different ways based on its context. There’s no Platonic essence of evangelicalism, but rather, as Wittgenstein argues in Philosophical Investigations, the meaning of a word is found in its use.

While Merritt is correct that it would be weird to consider Wheatley an evangelical in certain times and contexts, Kidd’s use of the term is quite appropriate relative to the time and context he was describing.

In Merritt’s defense, it has become nearly, might we say, useless to use the word “evangelical” without some accompanying adjective to specify whom or what one is describing—as Kidd himself has elsewhere acknowledged.

In my last post, I mentioned an article by one of my former college professors and personal mentors, Timothy Erdel (“Brother Tim”), in which he defines “evangelical” from a number of angles: historical, contemporary, theological, and behavioral.* In this post, I want to focus on the seven historical meanings of “evangelical” he describes in order to answer whether and how they’re compatible with Anabaptism.

(1) New Testament use of “evangelical”

Erdel notes that the New Testament frequently uses the Greek word euangélion to refer “to the basic message preached, taught, lived, and fulfilled by Jesus Christ.” According to the New Testament usage, “the Good News [euangélion] is that with the coming of Jesus, the Kingdom of God arrived on earth in a decisive way. Jesus came to bring Jubilee, Good News to the poor, release for captives, sight to the blind, and freedom for the oppressed.” The euangélion, writes Erdel, “stands in opposition to Roman power and military might, calling followers of Jesus to instead put on the whole armor of God in order to enter into spiritual warfare.”

This first use of “evangelical” is not only compatible with Anabaptism; it’s kind of the bread and butter of Anabaptist thought and life.

(2) Medieval use of “evangelical”

Erdel writes, “Numerous prophetic, reforming, and ascetic movements arose within the Roman Catholic Church during the Middle Ages that attempted to take seriously the teachings of Jesus, calling for a return to the four Evangels.” Erdel identifies both groups that broke with the Catholic Church, including the Waldensians, Lollards, and Hussites, and religious orders that arose within the Catholic Church, including the Benedictines and Franciscans.

This second use of “evangelical” is also compatible with Anabaptism. While Anabaptists have a bit of a rocky relationship with medieval Catholicism, they tend to love “evangelical” Catholic figures like St. Francis and to view the various medieval reform movements as precursors to the 16th-century radical (Anabaptist) reformation.

(3) Reformation era use of “evangelical”

Erdel writes, “The Reformation era set the stage for subsequent understandings of the term ‘evangelical.’ All four major streams of the Protestant Reformation—Lutheran, Reformed, Anglican, and Anabaptist—originally claimed the term; and, whatever their other differences, all four shared two major emphases that have been linked ever since to the word evangelical”—namely, the insistence that salvation comes solely by the grace of God through faith in the person of Jesus Christ (sola gratia, sola fides, and solus Christus) and the insistence on the primacy of Scripture (sola scriptura).

While some contemporary Anabaptists would quibble with the way some of their evangelical friends use the solas, it should go without saying that this third use of “evangelical,” which was claimed by the 16th-century Anabaptists themselves, is compatible with Anabaptism.

(4) 17th to 19th-century use of “evangelical”

Erdel writes, “Pietism, Puritanism (including Baptist and Friends/Quaker offshoots), revivalism, Methodism, and numerous other renewal movements emerged in the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries, reacting primarily against nominal Protestants in state churches.” (Incidentally, this is the use of “evangelical” that Kidd deployed to describe Wheatley.)

This fourth use of “evangelical” is arguably where tensions begin to arise with Anabaptism. On the one hand, Erdel notes that some of these groups “described themselves as believer’s churches or free churches, often embracing believer’s baptism and the separation of church and state,” and some “were influenced by Anabaptists on other points as well, retaining the strong Anabaptist foci on community, humility, loving service, discipleship, and the refusal to bear arms.”

On the other hand, some Anabaptists have worried that these movements were responsible for making evangelicalism other-worldly, individualistic, and generally averse to social concerns. This is one of the arguments of Mennonite historian Theron Schlabach’s classic 1980 book, Gospel Versus Gospel, which has been taken as, well, gospel truth by subsequent Mennonite historians. Some Pietist historians, such as Chris Gehrz, have challenged this view of Pietism as a mischaracterization.

In short, some Anabaptists would be much more comfortable claiming this fourth understanding of “evangelical” than others. While Anabaptism is compatible with this use of “evangelical,” the relationship is complicated.

(5) Early 20th-century use of “evangelical”

Erdel writes, “Fundamentalism emerged primarily as an American evangelical Protestant attempt to affirm decisive Christian doctrines that were in danger of being discarded by theologians more interested in accommodating Christianity to secular modernism than in defending biblical supernaturalism.” However, this movement “took on a more sharply polemical edge,” “became known as separatists,” and eventually “became social and political reactionaries,” even “openly championing segregation and other forms of racism.”

While some Mennonites, such as early 20th-century theologian Daniel Kauffman, were comfortably at home within the fundamentalist movement (as discussed by Ben Wetzel and Nathan Yoder in The Activist Impulse), the fundamentalist focus on right doctrine (orthodoxy) often at the expense of right practice (orthopraxis) sits uneasily with many Anabaptists today. And while Anabaptists have themselves been considered “separatists” by mainstream Christians, most would be uncomfortable being considered evangelicals of a fundamentalist stripe. And, at their best, Anabaptists have rejected the uglier sides of fundamentalism, such as its implicit and sometimes explicit racism.

In short, while this fifth use of “evangelical” has historically been claimed by some Anabaptists, its tensions with Anabaptism are so strong as to almost lead to a breaking point.

(6) Mid-20th-century use of “evangelical”

Erdel next describes the neo-evangelical movement, which was a mid-20th-century reaction against the excesses of the fundamentalist movement by conservative leaders like Billy Graham and Carl F. H. Henry. This movement is largely responsible for many of the evangelical institutions still around today, such as the National Association of Evangelicals, Christianity Today, and Fuller Theological Seminary.

If the fundamentalist movement took the tensions between evangelicalism and Anabaptism to the breaking point, neo-evangelicalism brought the tensions back to the level of the 19th century. Many so-called neo-Anabaptists are children of neo-evangelicals who have been influenced by evangelical-friendly Anabaptists like John Howard Yoder and Ron Sider. As Anabaptist historian David Swartz argues in his chapter of The Activist Impulse, the evangelical left (Jim Wallis et al.) in particular was directly influenced by Anabaptist theologians.

All that to say, this sixth use of “evangelical” is also compatible with Anabaptism, though, as with the fourth use, it’s not without its tensions.

(7) 21st-century use of “evangelical”

While readers in North America might think that the evangelical pendulum is swinging back toward the worst of fundamentalism in the 21st century, Erdel helpfully turns his attention instead to 21st-century global evangelicalism. He argues that “most prophetic voices come from overseas and rarely get heard in North American evangelical settings.” Erdel thus identifies a “new evangelical global majority that today dwarfs Anglo-American evangelicals.” Among other traits, Erdel identifies global evangelicals’ understanding that “from the beginning Jesus brought Good News to the poor,” that “his message was one of liberation and healing,” and that evangelicals in the North often preach “a truncated gospel, one deaf to the cries of the oppressed.” In short, “majority world evangelicals want a whole gospel for the whole person.”

Such criticisms of North American evangelicalism by global evangelicals sound strikingly similar to Anabaptist criticisms of evangelicalism. Thus, ironically, in as much as contemporary Anabaptists are in tension with contemporary North American evangelicalism, they demonstrate just how compatible they are with this seventh use of “evangelical.”

If we look at the tally sheet, then, we find that of Erdel’s seven historical uses of “evangelical,” Anabaptists are largely compatible with (1), (2), (3), and (7); they have some tensions with (4) and (6); and they’re largely incompatible with (5).

What do you think of Erdel’s seven uses? Do you agree with my assessment of their compatibility with Anabaptism? Let me know in the comments.

*See Timothy Paul Erdel, “The Evangelical Tradition in the Missionary Church: Enduring Debts and Unresolved Dilemmas,” Reflections: A Publication of the Missionary Church Historical Society 13–14 (2011–12): 74–109, available through the ATLA Religion Database.